What is Australia looking for in its poet laureate? Literary and popular poetry don’t always intersect

- Written by Peter Kirkpatrick, Honorary Associate Professor, University of Sydney

The inaugural Australian poet laureate will be appointed in 2025 as part of the federal Labor government’s new National Cultural Policy, Revive.

The intention to create the official position was announced, with some fanfare, at the beginning of 2023. But there is still no clear indication of how a suitable candidate will be selected, what criteria will be used, and the precise nature of the role. We still do not know what, exactly, an Australian poet laureate will be expected to do, or to achieve.

When the position was announced, academic Valentina Gosetti called it a “an unmissable opportunity” and hoped it would “reflect the call for diversity” embodied in Revive. One can only welcome any public initiative that acknowledges the greater diversity of contemporary Australian poetry, where Indigenous, non-Anglo, queer and all-abilities people are now represented.

But what about the diversity of poetry itself? I mean those genres that call themselves poetry, or might be deemed “poetry-adjacent” but pass under the radar of institutions such as the academy, the publishing industry and the literary awards system.

How would a poet laureate “speak” to the spoken word, slam or hip-hop communities, or to bush poets, or to songwriters?

Good bad poetry

The dominant intellectual model for poetry in the West remains the romantic-modernist version that emphasises its wow factor: its capacity to transform or estrange language in exciting, aesthetically challenging ways, often at the level of the individual image.

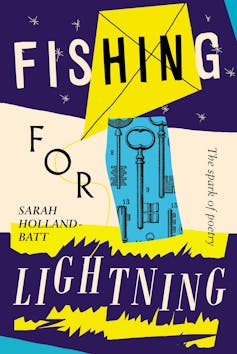

As Sarah Holland-Batt expresses it in her study of Australian poets, Fishing for Lightning: The Spark of Poetry (2021): “Poems are full of surprises: each line is a little detonation of language and imagery, each stanza a series of swift steps into the unknown.”