Suffragettes resurrected, maternal ambivalence and toxic teens: two Australian novels impress, but one overpromises

- Written by Liz Evans, Writer, author, journalist, Associate Lecturer in English & Writing, University of Tasmania

Earlier this year, I spent a day immersed in the second wave of British feminism at Tate Britain’s Women In Revolt: Art and Activism in the UK 1970-90. More of an event than an exhibition, the show was brimming with multimedia installations and artworks celebrating 20th-century, grass-roots activism.

I was equally struck by the audience and the exhibition. The gallery was buzzing as multiple generations gathered to learn and reminisce about the creative, politically engaged, socially diverse communities of women who altered British culture 50 years ago.

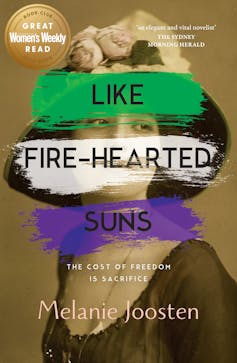

As their name suggests, second-wave feminists were not the first women to agitate for change. The pioneering work was done by suffragettes (the first-wave feminists), as Melanie Joosten explains in her vibrant new novel, Like Fire-Hearted Suns.

Review: Like Fire-Hearted Suns – Melanie Joosten (Ultimo), Thanks for Having Me – Emma Darragh (Allen & Unwin), Lead Us Not – Abbey Lay (Viking)

Unlike their successors, first-wave feminists were mostly white, wealthy women, and the movement was characterised by structural privilege. But Joosten’s clever choice of protagonists allows her to critique this inherent issue, while detailing the struggles and dreams of the individuals involved.

Women in Revolt celebrates 20th-century, grass-roots activism.A suffragette prison story

A fictionalised account based on historical research, the story begins in 1908 and revolves around two young students, Catherine Dawson and Beatrice Taylor. The third protagonist is prison warden Ida Bennett, who oversees the suffragette inmates of Holloway prison.

Ida, a widow of mixed ancestry with two young boys, is clearly distinct from the well-to-do Catherine and Beatrice. Resentful of the uppity attitudes and frivolous demands of her prisoners, her distress is further complicated by her racist treatment and the traumatic burden of having to force-feed the inmates when they go on hunger strike. But Ida is also a single working parent, unable to raise her own children: she understands the need for change more than most.

Catherine and Beatrice share student digs, similar wealthy backgrounds and a belief in women’s voting rights. They are also fiercely critical of each other’s lobbying styles and contrasting political approaches.

Beatrice is happy to throw bombs and smash windows as a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, even though this results in repeated arrests and nightmarish spells in Holloway with Ida.

Catherine prefers the pacifist campaigns of the Women’s Freedom League and sells copies of the League’s own newspaper, The Vote, while petitioning the government. Catherine does not approve of Beatrice’s tactics, and Beatrice deems Catherine’s actions to be ineffective.

Together with Ida’s conflicted attitude, the womens’ mutual irritation and political divide adds personal depth and insight to the historical context of their story. The varied perspectives remind the reader feminism has always been a pluralist discourse.