‘I was who I wasn’t’: McKenzie Wark’s memoir of late transition envisions a less gender-restrictive world

- Written by Anna Szorenyi, Lecturer in Gender Studies, University of Adelaide

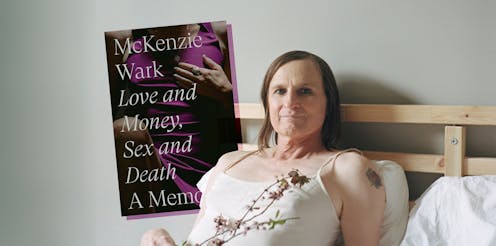

McKenzie Wark is a cultural and social critic who teaches at the New School in New York. Her new memoir, Love and Money, Sex and Death, is structured as a series of letters to people she has known: her younger self, her mother and sister, her ex-wife of 20 years, more recent lovers, some fictional people – even a god.

In this series of letters, Wark speaks to her past and imagines possible futures. She muses about how her life has changed since coming out as transgender in 2017 at the age of 56, but she also writes evocatively and fiercely about the loss of her mother as a child, her life and relationships in New York, and her visions for a less gender-restrictive world.

Love and Money, Sex and Death: A Memoir – McKenzie Wark (Verso)

This is a book which has a lot to say about being trans, but it deliberately avoids becoming a linear story of discovery of a “true” self. Instead, Wark shows us how a “self” is made from its relationships, through “fights and feuds”, through “covens of care”. There is a continual sense of her reconstructing herself through and with others.

This is conveyed in the style and form of the book. Part of the beauty of an epistolary memoir is that Wark gets to write throughout in the second person, giving the book a feeling of intimacy. The concept of “writing to a younger self” in the first and last chapters allows Wark to reconstruct a life in hindsight, retro-engineering the story to fit her late change of identity.

This is done with a light touch. Wark writes to her younger self as to another, someone she knows well, but who has their own problems, perspectives and choices. Stories of the past are as much “about” the present self as the facts of what actually happened. Wark writes:

When one transitions to another sex, the past comes back as if in a different medium. Memories tell not of who one was but who one wasn’t. I was who I wasn’t for the longest time. Transition brings rushes of the past back. Shots for an incomplete home movie. I had to edit memory as I edited flesh.

These “edited memories” are told in ways that foreshadow, without reducing to, any story of “I was always a woman”. Wark complains that trans people are always pushed to tell essentialist stories about their gender. She presents her life as a series of encounters and experiments, which happened to turn out this way, but might have gone another. “I’m writing this to your own future, or a possible one at least,” she writes on the first page, addressing a young McKenzie.

I’m not going to say you are a girl, or that you always were. You’ve been reading transsexual memoirs on the sly already and not finding yourself in that ‘born in the wrong body’ story. You feel like your body is already a girl’s body. […] Maybe some sorts of transsexual people ‘always knew’, but you didn’t. You’re always swerving, blindly falling through gender.

Wark’s vulnerability and openness about failures, letting people down, not knowing the plot, is part of the book’s aesthetic. But this does not make it a sad story, even as it canvasses death and failed love. As Jack Halberstam argues in The Queer Art of Failure, failure can open up alternate possibilities for life and love.

Wark is often cynical about the future: “There’s no past, no arcadia. But no future either.” All the same, the book carries the strong themes of care and desire for revolution or utopia, which make it a deeply optimistic work.

Read more: Judith Butler: their philosophy of gender explained

Vulnerability and receptivity

While not sure she was always a woman, Wark writes that she “need[s] to feel feminine”. This does not just mean that she needs to paint her nails (although that, too). It is an overtly sexual “femme” desire: to be exposed, penetrated, made to feel her own vulnerability, openness and receptivity.

One of the things the book does is to enact the queer understanding that this “femme” does not need to be the property of people of any particular gender. Even though she has transitioned into womanhood, Wark maintains a deliberate blurriness about what gender means. Ultimately, she suggests, there can be more revolutionary potential in failing to live up to a single gendered identity than in trying to achieve authenticity.

I wouldn’t say that being trans now is living my truth. I’d say it’s a better fiction.

In the first chapter of part three, McKenzie and “Veronica”, an elegant trans woman friend, talk over lunch in an expensive New York restaurant. Amid cocktails, disagreements and speculations about the other guests’ sexuality, McKenzie presents a full-fledged theory of trans women as utopian avant-garde.

The trans woman bears the burden of the absurdity of gender. She is the scapegoat for what everyone imagines they’re denied.

Precisely because trans women are accused of being deceptive, Wark suggests, they can lead towards a world where people are not constantly in thrall to unattainable “true” models of gender, but instead “make our being together with reference only to each other”.

The “Venus” chapter is addressed to a Black trans woman friend who committed suicide during COVID lockdown. It reports on the Brooklyn Liberation for Trans Lives protests for Black trans women. Here, Wark reflects that she has given up her status as a man, but become a middle-class white woman, a “Karen” (a name she had previously chosen for herself).

Following from the scenes in expensive New York restaurants, this (inevitably) feels a bit tokenistic at first. It finishes, though, in such a blaze of anger and ragged grief, of political will for revolution, connection and shared fate that we can glimpse a form of alliance that might be possible when the privileged are prepared to let themselves be undone.

The “hindsight” structure of the memoir means that the reader is always aware of time. Wark counts the years between herself and her past, herself and her future. “Your life as a woman will be brief,” she says to her younger self. “She’ll die young.”

In many ways this is a book about growing older. It addresses the themes of maturing and how priorities in relationships change over time: the gaining of a warmer, less anxious perspective.

Time was necessary for Wark to become her (if that is what she has done) self. The “trade-off with late transition” is ever-present, for better and worse. There is an insistent sense of time shortening ahead of her. But as with her sense of gender, Wark’s sense of time is fluid, often felt through music – jazz when she was younger, rave and ambient later. Time is felt in Wark’s writing, more than measured. It has a music of its own.

How long have we been here? How long are we dancing? […] We are in a pocket in time where there’s more time […] We go into weightless days, seconds, millennia. On the other side of the measure of beats is a time without measure.

Read more: What is essentialism? And how does it shape attitudes to transgender people and sexual diversity?

Freedom and joy

Wark often assumes an educated reader. Phrases like “This was postmodern aesthetics as Oedipal break-up” will make sense to some readers, but not others. Wark draws on her career as a media theorist, but is also happy to laugh at her “weird brain labour”. There are many funny (although still sometimes painful) moments. Of the dating app Tinder, she writes:

when I say I’m trans, they say it’s OK because they’re into kink. (Then ghost me.) They say they have several selves, only one of them female. (They all need a bath.)

One of the delicious things in this book is the sense of freedom that it invokes. Wark has lived a life of experimentation, following impulses, paying little heed to social conventions. She acknowledges that, at times, this has made her unreliable or even cruel. She does not shy away from responsibility and regret. But overall there is a sense of joy: a “capacity for delight”, as she says of a lover. At heart, these letters are love letters.

There is always more in a book than you can convey in a review, especially a book as fast-moving and kaleidoscopic as this one. But it could perhaps be summarised as a book written from the other side of multiple processes of undoing – loss of loved ones, restructuring of the body and identity, confrontations with violence and prejudice.

Love and Money, Sex and Death ricochets between sparkling defiance, unravelled grief, and furious hope. It always seeks connection with the others it addresses. It combines the personal and political through a philosophy of intimate coalition, in the name of a world where all can find a home and freedom. It’s a fun, wild, devastating ride. Read it.

Authors: Anna Szorenyi, Lecturer in Gender Studies, University of Adelaide