Exile on Main St turns 50: how The Rolling Stones' critically divisive album became rock folklore

- Written by Dean Biron, PhD in Cultural Studies; teaches in School of Justice, Queensland University of Technology

In May of 1972 the Rolling Stones released their 10th British studio album and first double LP, Exile on Main St. Although initial critical response was lukewarm, it is now considered a contemporary music landmark, the best work from a band who rock critic Simon Frith once referred to as “the poets of lonely leisure.”

Exile on Main St. was both the culmination of a five-year productive frenzy and bleary-eyed comedown from the darkest period in the Stones’ history.

By 1969 the storm clouds of dread building around the group had become a full-blown typhoon. First, recently sacked member Brian Jones was found dead, drowned in his swimming pool.

Then, as the decade ended in a rush of bleak portents, they played host to the chaos of the Altamont Speedway Free Concert, a poorly organised, massive free concert, which ended with four dead including a murder captured live on film.

Yet amidst all this the Stones produced Let It Bleed (1969) and Sticky Fingers (1971), two devastating albums that wrapped up the era like a parcel bomb addressed to the 1970s.

Songs like Gimme Shelter, the harrowing Sister Morphine, and Sway, which broods on Nietzche’s notion of circular time, exuded the kind of weary grandeur that would define Exile.

Rock folklore

The story behind Exile on Main St. has become rock folklore. Fleeing from England’s punitive tax laws, the Stones lobbed in a Côte d'Azur mansion that was a Gestapo HQ during World War II.

Mick Jagger was largely sidelined, spending much of the time in Paris with pregnant wife Bianca. The musicians were jammed into an ad-hoc basement studio, a cross between steam-bath and opium den, powered by electricity hijacked from the French railway system. The house was beset by hangers-on, including the obligatory posse of drug-dealers.

Yet with control ceded to the nonchalant, disaster-prone Keith Richards – the kind of person a crisis would want around in a crisis – they somehow harnessed the power of pandemonium.

The result was a singular amalgam of barbed soul, mutant gospel, tombstone blues and shambolic country, as thrilling in its blend of familiar sources as works by contemporaries Roxy Music and David Bowie were in the use of alien ones.

Jagger shuffles his deck of personas from song to song like a demented croupier, the late, great drummer Charlie Watts supplies his customary subtle adornments, and a cast of miscreants – most crucially, pianist Nicky Hopkins and producer Jimmy Miller – function as supplementary band members.

All 18 tracks contribute to the ragged perfection of the document as a whole. Tumbling Dice and Happy are textbook rock propelled by a strange union of virtuosity and indolence. And there is an undeniable beauty to the likes of Torn and Frayed and Let it Loose, albeit a beauty that is tentative, hard-earned.

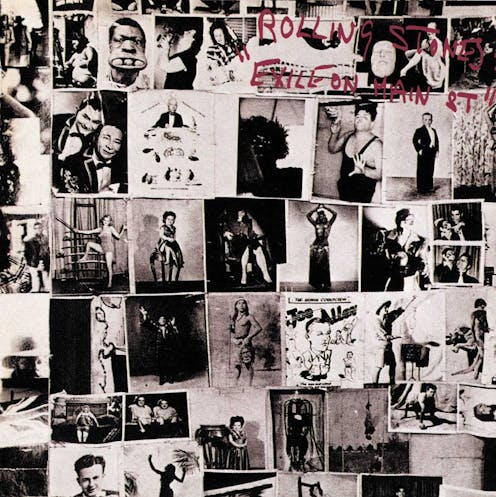

The package is completed by its distinctive sleeve art, juxtaposing a collage of circus performers photographed by Robert Frank circa 1950 with grainy stills from a Super-8 film of the band and a mural dedicated to Joan Crawford.

Exile confused audiences at first: Writer John Perry describes its 1972 reception as mixing “puzzlement with qualified praise”. The response of critic Lester Bangs was typical. After an initial negative review, Bangs came to regard it as the group’s strongest work. Critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine confirms that the record over time has become a touchstone, calling it a masterful album that takes “the bleakness that underpinned Let It Bleed and Sticky Fingers to an extreme.”

Inspiration

The roll call of artists inspired by Exile is extensive, from Tom Waits and the White Stripes to Benicio del Toro and Martin Scorsese. But two album-length homages stand out.

In 1986, underground punks Pussy Galore concocted a feral, abstract facsimile of the entire double-LP. In 1993, singer-songwriter Liz Phair used the original as a rough template for her acclaimed Exile in Guyville.

Nonetheless, journalist Mark Masters notes that by the 1980s, the social and cultural circumstances that produced Exile were waning as acts such as Minutemen, Mekons, The Go-Go’s and Fela Kuti gave listeners access to fresh modes of rebellion.

Read more: Brown Sugar: why the Rolling Stones are right to withdraw the song from their set list

Circa 1972, the Rolling Stones deserved the title “greatest rock and roll band in the world.” That it is still claimed 50 years on shows how classic rock continues to overbear all that followed.

The grandfathers of rock

When in 2020 Rolling Stone magazine made a half-hearted attempt to tweak the classic rock canon – elevating Marvin Gaye, Public Enemy and Lauryn Hill alongside or above Exile and the Beatles – the response was predictably unedifying.

One reader complained that the magazine was catering to “young people with no musical history and older people who don’t know anything.” Others raged that rap is not music and the list was proof of rampant political correctness.

Such archaic, ignorant language is typical of gatekeepers of the classic rock tradition. It is a language of exclusion, ensuring that exceptional new music by, say, Fiona Apple (which sounds something like rock) or Liz Harris (which sounds rather different) will always be rated below what came before.

The Rolling Stones have an inevitable, if ambiguous, relationship to all of this. In terms of race, writer Jack Hamilton argues that they were always “fiercely committed to a future for rock and roll music in which black music and musicians continued to matter.”

How they intersect with gender is perhaps more troubling, though also conflicted. While eminent female musicians such as Joan Jett, Carrie Brownstein and Rennie Sparks continue to champion the Stones, their role as leading purveyors of an inherently masculine, increasingly archaic musical form cannot be avoided.

Exile on Main St. is a significant album made by a bunch of haggard rebels whose heyday (and rebellion) is past but whose art lives on in complex ways.

Along with Sly and the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On and Neil Young’s Tonight’s the Night, it fits snugly into an aesthetic of washed out, narcotic-smeared masterpieces from the early seventies.

Authors: Dean Biron, PhD in Cultural Studies; teaches in School of Justice, Queensland University of Technology