Your unvaccinated friend is roughly 20 times more likely to give you COVID

- Written by Christopher Baker, Research Fellow in Statistics for Biosecurity Risk, The University of Melbourne

As lockdowns ease in New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT, and people return to work and socialising, many of us will be mixing more with others, even though a section of the community is still unvaccinated.

Many vaccinated people are concerned about the prospect of mixing with unvaccinated people. This mixing might be travelling on trains or at the supermarket initially. But also at family gatherings, or, in NSW at least, at pubs and restaurants when restrictions ease further, slated for December 1.

Some people are wondering, why would a vaccinated person care about the vaccine status of another person?

Briefly, it’s because vaccines reduce the probability of getting infected, which reduces the probability of a vaccinated person infecting someone else. And, despite vaccination providing excellent protection against severe disease, a small proportion of vaccinated people still require ICU care. Therefore some vaccinated people may have a strong preference to mix primarily with other vaccinated people.

But what exactly is the risk of catching COVID from someone who’s unvaccinated?

Read more: As Melbourne cautiously opens up today, what lies ahead?

What’s the relative risk?

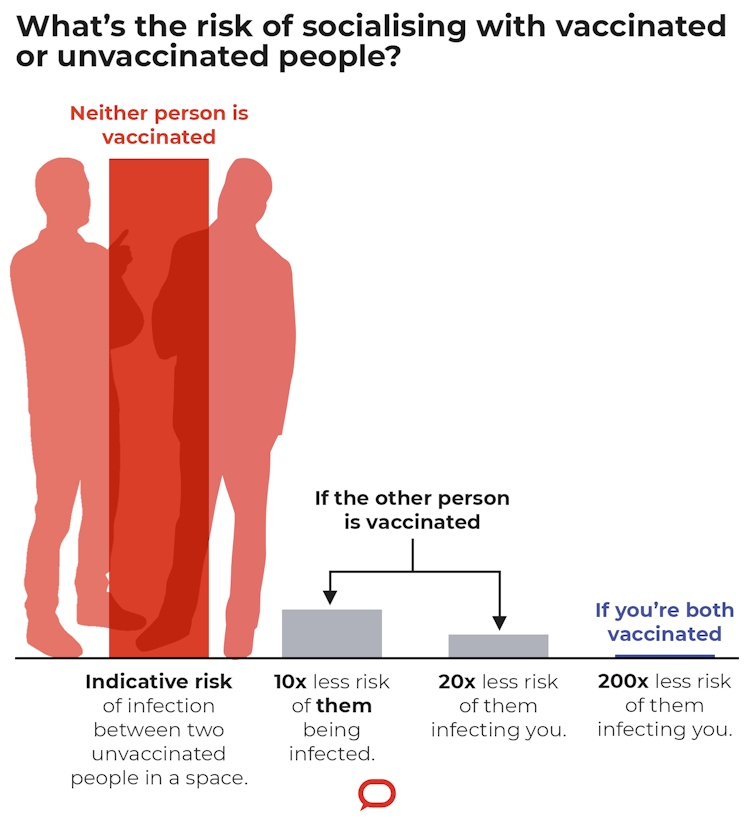

Recent reports from the Victorian Department of Health find that unvaccinated people are ten times more likely to contract COVID than vaccinated people.

We also know that vaccinated people are less likely to transmit the disease even if they become infected. The Doherty modelling from August puts the reduction at around 65%, although more recent research has suggested a lower estimate for AstraZeneca. Hence for this thought experiment, we’ll take a lower value of 50%.

As the prevalence of COVID changes over time, it’s hard to estimate an absolute risk of exposure. So instead, we need to think about risks in a relative sense.

If I were spending time with an unvaccinated person, then there’s some probability they’re infected and will infect me. However, if they were vaccinated, they’re ten times less likely to be infected and half as likely to infect me, following the numbers above.

Hence we arrive at a 20-fold reduction in risk when hanging out with a vaccinated person compared to someone who’s not vaccinated.

Even though rapid tests provide a reduction in risk, they don’t replace vaccines.

When used in conjunction with high levels of vaccination, rapid tests would provide improved protection for settings where we’re particularly keen to stop disease spread, such as hospitals and aged care facilities.

Read more: Home rapid antigen testing is on its way. But we need to make sure everyone has access

Consequently, despite the high efficacy of COVID vaccines, there are still reasons a vaccinated person would prefer to mix with vaccinated people, and avoid mixing with unvaccinated people.

This is particularly true for those at higher risk of severe disease, whether due to age or disability. Their baseline risk will be higher, so a 20-fold reduction in risk is more meaningful.

Authors: Christopher Baker, Research Fellow in Statistics for Biosecurity Risk, The University of Melbourne