Vital Signs: the Greens' super-profits tax idea could end up burning muscle, not fat

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

Earlier this year, the Australian Greens proposed a wealth tax on billionaires straight out of the (former US presidential candidate) Elizabeth Warren playbook.

This week it added what it called a “tycoon tax” that would tax so-called super-profits made by companies with annual turnovers of more than A$100 million.

It might not be the winner it seems.

If Australian taxpayers want to get more tax from super-profitable companies there might be better ways to do it.

Under the Greens proposal some companies, even large ones, would escape the extra annual tax. It would apply only to that part of their post-tax profits that exceeded an “allowance for a corporate equity”.

The allowance would be 5% of the value of the company plus the long-term bond rate, which at present is 1.2%, meaning at the moment the threshold would be a post-tax return on capital of 6.2%

Extra profit — so-called super-profit above the threshold — would be taxed at 40%, meaning almost half of it would lost.

An idea with a backstory

The Greens system is the system (and the rate) recommended by the Henry Tax Review for taxing the larger-than-normal profits from mining, and it’s the system used since 1988 for the larger than normal profits from off-shore petroleum.

What the Greens propose would apply not only to the earnings of Australian companies but also to the share of a multinational’s operations in Australia.

The mining sector would be dealt with on a project-by-project basis rather a company-by-company basis, which is what happened with Labor’s short-lived minerals resource rent tax (also 40%) between 2012 and 2014.

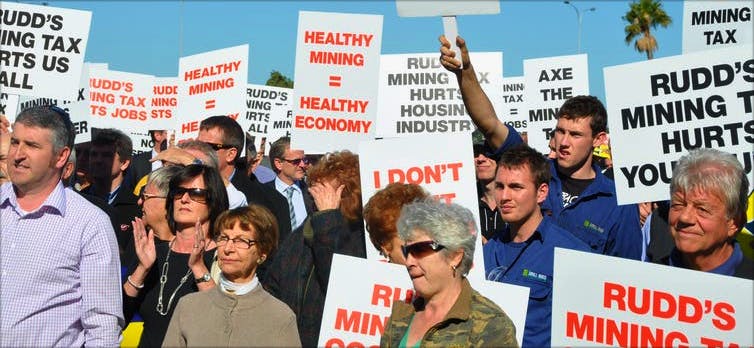

A 2010 Perth rally against the Resource Super Profit Tax proposed by the Rudd Labor government. Josh Jerga/AAP.

Josh Jerga/AAP

A 2010 Perth rally against the Resource Super Profit Tax proposed by the Rudd Labor government. Josh Jerga/AAP.

Josh Jerga/AAP

Some years ago the idea was put forward by the Business Council of Australia as part of a plan to remove the tax on normal company profits (something the Greens are not proposing to do).

In its 2009 submission to the Henry Tax Review, the Business Council said taxing only returns that exceeded a “normal” return had the “potential to stimulate investment both for locally based companies and inbound investors”.

But there are problems with the idea, as the Business Council acknowledged.

It’s hard to get right

One problem is that it is hard to know where to set the threshold between “normal” profit and “super” profit (what economists call “economic rent” which is returns in excess of those needed to justify the activity).

The threshold is unlikely to be 5% plus the bond rate across the entire economy.

If we end up not only taxing excessive economic rents but also genuine needed returns we might damage the engine of the economy. We would be like an athlete who is burning muscle as well as fat.

Read more: The resources tax: back to the future?

Investors take a risk when they put money into a business.

Sometimes the investment goes well, other times it will fail. Grabbing 40% of the extra upside, but leaving investors to wear all of the downside or accumulate losses to offset against future profits, would create an asymmetry.

It’d seem like “heads Adam Bandt wins, tails I lose”.

Many of the companies that make so-called super-profits would stay here grudgingly. The big five banks make profits way in excess of the threshold. Some multinational franchise operations probably make them as well.

We can’t be certain companies would stay

But other companies might decide to wind down their operations in Australia, redirecting investment to somewhere else. Jobs and wages might suffer.

Also it would be hard to measure the capital base of the the company to work out how to measure the return and calculate how much of it was above 6.2%.

The Greens did the right thing getting the independent Parliamentary Budget Office to assess how much the tax would raise.

The PBO’s best guess is that the mining component would raise $124.78 billion over 10 years and the non-mining component $213.9 billion.

Read more: Coalition to axe mining tax, but petroleum will keep on giving

The costing of one of those components (the non-mining component) includes so-called “behavioural responses” which in this case means it assumes 20% less tax would be paid than calculated as companies restructured their affairs.

That might be too mild an assumption for such a big tax change.

The costing of the mining component has not been adjusted. Anyone who remembers Kevin Rudd’s mining super-profits tax remembers the threats of big behavioural responses. They helped end Rudd’s prime ministership.

There are more promising ideas

On Monday at the ANU Crawford Leadership Forum, former Australian finance minister Mathias Cormann, who is now secretary general of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, outlined a more promising proposal.

The OECD has developed a worldwide plan to get multinationals with annual revenues of more than €750 million (about A$1.2 billion) to pay a minimum tax rate of at least 15% all over the world.

US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen wants to go further. She is working on a global minimum corporate rate of 21%.

They are ambitious plans, but they have a real chance of success.

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW