Soeharto: the giant of modern Indonesia who left a legacy of violence and corruption

- Written by Tim Lindsey, Malcolm Smith Professor of Asian Law and Director of the Centre for Indonesian Law, Islam and Society, The University of Melbourne

This piece is the last in a series in collaboration with the ABC’s Saturday Extra program. Each week, the show features a “who am I” quiz for listeners about influential figures who helped shape the 20th century, and we publish profiles for each one. You can read the other pieces in the series here.

Soeharto was the giant of modern Indonesia.

For many Indonesians, his resignation in 1998 after 32 years in power is still a watershed moment. Much that has happened since has been a reaction against his rule, or an attempt to recreate it.

Despite his death in 2008, aged 86, the legacy of Soeharto’s authoritarian “New Order” regime continues to shape his country profoundly, for better and, often, for worse.

Bamboo hut beginnings

Soeharto’s rise to become the billionaire autocrat of the world’s fourth-most populous country would have seemed very unlikely in his childhood.

Born in 1921 in a bamboo hut in the Dutch East Indies, he had 11 half-brothers and sisters. He joined the Dutch colonial army in 1940 because he tore his only set of clothes and had to quit his clerical job.

Soeharto’s political and economic impact continues to loom large over Indonesia.

Mast Irham/EPA/AAP

Soeharto’s political and economic impact continues to loom large over Indonesia.

Mast Irham/EPA/AAP

The Japanese invasion in 1942 drove the Dutch out, and Indonesia declared independence at the end of the second world war. But the Dutch returned to reclaim their colonial empire in late 1945 and Soeharto joined the Indonesian forces fighting for independence. He rose quickly and finished the war a senior officer, but corruption allegations saw Soeharto kicked sideways in the 1950s.

Taking control of the army

The Dutch transferred sovereignty to Indonesia in 1949 and a liberal democratic system was set up. But this was soon crippled by political in-fighting and regional rebellions.

By 1959, it had been replaced – with the army’s blessing - with the “guided democracy” dictatorship of Indonesia’s first president Soekarno, the charismatic “Proclaimer of Independence”.

However, the army now felt threatened by the three million-strong Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), the world’s largest outside China and Russia. Fearing the PKI’s growing mass support, the army began to prepare for a showdown.

Tensions mounted, and on the evening of September 30, 1965, a group of leftist officers killed the army chief and five other senior commanders, announcing a take-over to prevent a right-wing coup.

Historians have long wondered why Soeharto (by then a major-general and commander of key strategic reserve forces in Jakarta) was left unscathed by the violence, and some believe he was in on the conspiracy. Certainly, he seems to have been in touch with plotters before the killings. In any event, he exploited events with great cunning, quickly moving to take control of the army and crush the coup attempt.

Presenting it to the public as a wider conspiracy by the PKI to seize power, he launched the systematic “root and branch” extermination of the communist party.

A bloodbath followed, as the army, with the help of militias, slaughtered at least 500,000 alleged leftists and detained around a million more. The left was annihilated in Indonesia and has never recovered.

Taking control of the country

These horrific events came to be glorified as the founding myth of the New Order, and the killers — many of whom became the new ruling elite — still enjoy complete impunity.

Within six months, Soeharto had toppled Soekarno. When troops surrounded his palace in March 1966, Soekarno fled to the hills outside Jakarta. Soeharto sent three generals after him, who extracted a transfer of presidential powers, probably at gunpoint.

Soeharto began his military career in the 1940s.

Wikimedia Commons

Soeharto began his military career in the 1940s.

Wikimedia Commons

Under its new president, Indonesia quickly made a dramatic Cold War u-turn from left to right — away from Soekarno’s “Peking-Pyonyang-Hanoi-Phnom Phen-Djakarta” axis, towards the United States.

Despite initial promises of a return to rule of law, the new regime turned out to be a repressive military-bureaucratic autocracy, with soldiers permeating every level of society, from politics and business down to villages. Their role was principally surveillance and intimidation, but Soeharto’s regime was always willing to use brutal force if it really felt threatened.

Soeharto maintained his position by institutionalising corruption and, in time, by stacking the legislature. He closely controlled the three permitted political parties, and imposed tight controls on the media. He was famously able to predict his inevitable election victories to within a few percentage points.

‘The Jakarta method’

Soeharto was welcomed enthusiastically in the west.

The US, which had connived in the extermination of the PKI, poured aid and military support into the new Indonesia. For them, Indonesia showed a better way of “stopping the dominos” (based on the now-discreted theory that a communist government in one nation see communist takeovers in neighboring states).

Instead of risking American boots on the ground — as in Korea and Vietnam — local communist movements could be stopped by helping local militaries and right-wingers seize power. As journalist Vincent Bevins has shown in his recent book, Soeharto’s example became known as “the Jakarta method”, motivating US covert operations across Latin America in the years that followed.

Under Soeharto, Indonesia became a key US ally.

Wikimedia Commons

Under Soeharto, Indonesia became a key US ally.

Wikimedia Commons

However, there is no denying western support and Soeharto’s decisions to open Indonesia to foreign investment and follow the advice of US-educated technocrats (known as the “Berkeley Mafia”), also delivered spectacular dividends for Indonesia.

Under Soeharto, poverty fell from 45% in 1970 to 11% in 1996, life expectancy rose from 47 in 1966 to 67 in 1997, and infant mortality was cut by 60%. His family planning program, while often repressive, was hailed as a success. Likewise, by 1983, primary school enrolment was 90% and the education gap between boys and girls almost closed.

Read more: Behind the coup that backfired: the demise of Indonesia's Communist Party

No other president of Indonesia has presided over so dramatic an improvement in economic conditions. In 1983, the legislature gave Soeharto the title “Father of Development”, and in 1985, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation awarded him a gold medal for helping Indonesia achieve rice self-sufficiency.

A few years later, the banking sector was deregulated. The number of banks increased by half between 1989 and 1991 alone, and more foreign funds flooded in.

Great wealth … and corruption

Certainly, some of this vast new wealth trickled down to the poor. Per capita GDP grew from US$806 (A$1,119) to US$4,114 (A$5,712) between 1966 and 1997, and a new middle class began to emerge.

However, much of the money stayed firmly in the hands of the ruling elite, thanks to corruption. Kickbacks, vast amounts skimmed from official budgets, and massive bribe revenues were paid to “charitable” foundations controlled by Soeharto, which then paid out to ensure elite support for the regime.

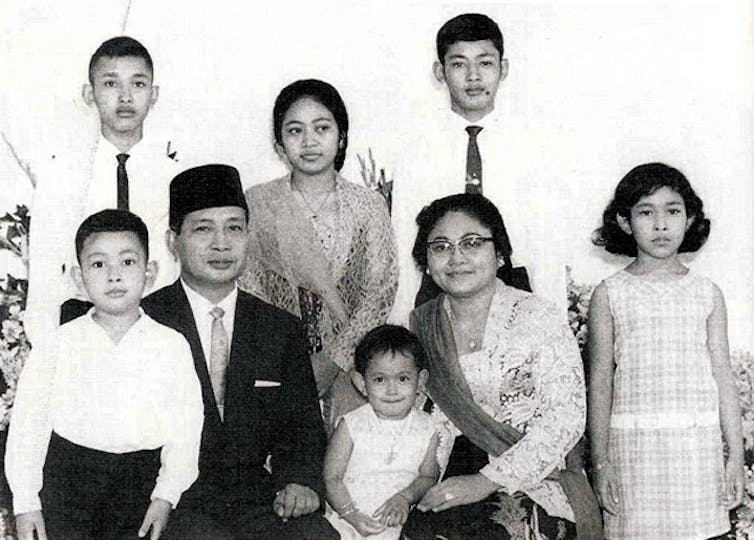

Soeharto’s family became rich and powerful under his leadership.

Wikimedia Commons

Soeharto’s family became rich and powerful under his leadership.

Wikimedia Commons

This system, described by Indonesia scholar Ross McLeod as a sophisticated franchise system, was key to keeping Soeharto in power for so long, regardless of calls for change.

Soeharto came from a broken family, and it is often claimed his great weaknesses was his inability to say “no” to his six children. Certainly, the “Cendana family” (named for the street where the Soeharto compound was located) became a byword for rapacious greed. Granted strategic monopolies, including in cloves, toll-roads and the national car project, the family had a stranglehold on the booming economy.

In 1998, Transparency International claimed the family had accumulated more than US$30 billion.

Collapse and ‘Reformasi’

Despite his vast power, Soeharto’s seemingly unassailable regime collapsed with surprising speed when the Asian Financial Crisis hit in 1997. The currency fell fast from Rp. 2,600, eventually reaching about Rp 20,000 to the US dollar. Indonesian borrowers could not service foreign currency loans and around 80% of listed companies and banks were soon insolvent. The IMF stepped in, raising interest rates to 70%.

Soeharto’s 1998 resignation was a watershed moment for Indonesia.

Charles Dharapak/AP/AAP

Soeharto’s 1998 resignation was a watershed moment for Indonesia.

Charles Dharapak/AP/AAP

Soeharto once again won rigged elections in March 1998, but to no avail. Students occupied the legislative building, demanding “reformasi”, and growing political tension was accompanied by rioting, often targeting the ethnic Chinese. In May 1998, with smoke from burning malls shrouding his gridlocked capital, he resigned in a live TV broadcast.

For the next decade, leaders of the “Reformasi” movement gradually demolished every pillar of the New Order in an attempt to build Indonesia’s second liberal democratic system. In response, Soeharto’s cronies closed ranks around the elderly recluse, protecting him from trial until his death in 2008.

The ghost remains

The ghost of Soeharto has proved restless. Most of the New Order elite survived his fall with their power and wealth largely intact. His children are still enormously rich business figures, and no one has ever been tried for the massacres of 1965.

In fact, many major political figures today were powerful under the New Order. To name just two, former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, was a New Order general, while Soeharto’s former son-in-law, Prabowo Subianto, who allegedly abducted and tortured anti-regime activists in 1998, is now defence minister.

Read more: A requiem for Reformasi as Joko Widodo unravels Indonesia's democratic legacy

It also remains to be seen whether Soeharto’s authoritarianism is really gone for good. Many observers agree Indonesia’s fragile democracy now looks increasingly threatened under the current president, Joko Widodo.

There have been repeated calls for “Pak Harto” to be formally recognised as a national hero. For many young Indonesians who never experienced the repression of the New Order, Soeharto’s rule now seems a nostalgic time of stability, security and prosperity.

Many suspect the ruling elite might be quite happy with a return to a system like the one Soeharto perfected. Some even fear they are working on it now.

Authors: Tim Lindsey, Malcolm Smith Professor of Asian Law and Director of the Centre for Indonesian Law, Islam and Society, The University of Melbourne