Australia is at risk of taking the wrong tack at the Glasgow climate talks, and slamming China is only part of it

- Written by Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Buried within the prime minister’s response to the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is just about everything we’re at risk of getting wrong at the Glasgow climate talks in October.

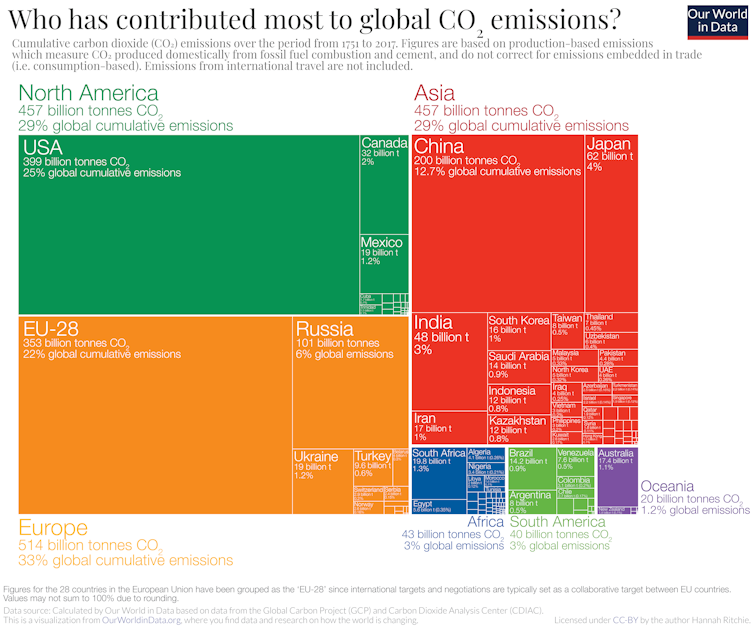

After slamming China — whose emissions per person are half of Australia’s — for not doing more to cut emissions, Scott Morrison said the Glasgow talks were the “biggest multilateral global negotiation the world has ever known”.

If he treats the talks as just another (big) negotiation, we’re in trouble.

The way the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade usually treats negotiations is hold something back, hold out the prospect of “giving it up,” and then only make the concession if the other side gives something in return. Even if holding back damages Australia.

Cars are a case in point. From an economic point of view, there is no reason whatsoever to continue to impose tariffs (special taxes) on the import of cars — none, not even in the eyes of those who support the use of tariffs to protect Australian jobs. Australia no longer makes cars.

Yet the tariff remains, at 5%, making it perhaps A$1 billion harder than it should be for Australians to buy new cars (although nowhere near as hard as it was in the days when the tariff was 57.5%).

The tariff seems to be in place largely to give the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade something to negotiate away in trade agreements: for use as what the Productivity Commission calls “negotiating coin”.

Australia removed tariffs on cars from Korea but kept them in place more broadly.

Tricky_Shark/Shutterstock

Australia removed tariffs on cars from Korea but kept them in place more broadly.

Tricky_Shark/Shutterstock

Here’s how it worked in the 2014 Australia-Korea Free Trade Agreement. Australia agreed to remove the remaining 5% tariff on Korean cars, “with consumers and businesses to benefit from downward pressure on import prices”.

But Australia didn’t remove the tariff on car imports altogether, which would have given us a much bigger benefit but denied the department negotiating coin.

The next year the department did it again, agreeing to give up the tariff on imported Japanese cars in the Japan-Australia Economic Partnership Agreement (but not on other cars) so Australians could “benefit from lower prices and/or greater availability of Japanese products”.

Two years later, it did it again, with cars from China.

When the UK and European agreements are negotiated, it’ll do it there too.

Australia holds back reforms

Eventually Australians will get what they are entitled to. But the point is that rather than advancing the cause of free trade, the department has held back, treating a win for the other side as a loss for us, when it wasn’t.

The Centre for International Economics believes the much bigger earlier set of tariff cuts lifted the living standard of the average Australian family by A$8,448.

Had our trade negotiators been in charge, we would still be waiting. Instead the Hawke and then the Keating governments pushed through unilateral reductions, asking for nothing in return.

As former Trade Minister Craig Emerson put it, this gave Australia “credibility in international trade negotiations way beyond the relative size of our economy”.

Does that sound like the sort of thing Australia might need at Glasgow, to have enough credibility to urge even bigger emitters to deliver the kind of cuts on which our futures and future temperatures depend?

It won’t work with China

The prime minister is right to say that China is the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter, even though its emissions per person are low. Its high population means it accounts for 28% of all the greenhouse gases pumped out each year. The next biggest emitter, the United States, accounts for 15%

But China’s status is new. Until 2006 it pumped out less per year than the United States. Because the US has had mega-factories and heating and so on for so much longer, it is responsible for by far the biggest chunk of the greenhouse gasses already in the atmosphere: 25%, followed by the European Union with 22%.

China might reasonably feel that countries like the US that have done the most to create the problem should do the most to fix it.

Like Australia, the US pumps out twice as much per person as China and has much more room to cut back.

On the bright side, China knows that being big means it is in a position to make a difference to global emissions in a way that other countries cannot on their own. And that’s a position that can benefit its citizens.

China’s latest five-year plan, adopted in March, commits it to cut its “carbon intensity” (emissions per unit of GDP) by 18%. If it beats that five-year target by just a bit (and it has beaten its previous five-year targets) its emissions will turn down from 2025.

It is aiming for net-zero emissions by 2060.

Australia needs China’s help

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change finds that Australia is especially susceptible to global warming. We’re facing less rain in winter, longer heatwaves, drier rivers, more arid soil and worse droughts.

We are right to want China to do more, but the worst way to achieve it is to say “we won’t lift our ambition until you lift yours”.

Hardly ever a worthwhile strategy, it is particularly ineffective when we don’t have bargaining power.

Read more:

Climate change has already hit Australia. Unless we act now, a hotter, drier and more dangerous future awaits, IPCC warns

The only power we’ve got is to set an example, unilaterally, as we did with tariffs. And to ramp up our ambition.

If Australia said it would do more, and didn’t quibble, it might just count for something.

It’s all we can do, and it’s the very best we can do.

China might reasonably feel that countries like the US that have done the most to create the problem should do the most to fix it.

Like Australia, the US pumps out twice as much per person as China and has much more room to cut back.

On the bright side, China knows that being big means it is in a position to make a difference to global emissions in a way that other countries cannot on their own. And that’s a position that can benefit its citizens.

China’s latest five-year plan, adopted in March, commits it to cut its “carbon intensity” (emissions per unit of GDP) by 18%. If it beats that five-year target by just a bit (and it has beaten its previous five-year targets) its emissions will turn down from 2025.

It is aiming for net-zero emissions by 2060.

Australia needs China’s help

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change finds that Australia is especially susceptible to global warming. We’re facing less rain in winter, longer heatwaves, drier rivers, more arid soil and worse droughts.

We are right to want China to do more, but the worst way to achieve it is to say “we won’t lift our ambition until you lift yours”.

Hardly ever a worthwhile strategy, it is particularly ineffective when we don’t have bargaining power.

Read more:

Climate change has already hit Australia. Unless we act now, a hotter, drier and more dangerous future awaits, IPCC warns

The only power we’ve got is to set an example, unilaterally, as we did with tariffs. And to ramp up our ambition.

If Australia said it would do more, and didn’t quibble, it might just count for something.

It’s all we can do, and it’s the very best we can do.

Authors: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University