Hidden women of history: how mother of 8, Mary Anne Allen, made do on the goldfields amid gunshots, rain and sly grog

- Written by Katrina Dernelley, PhD Candidate in History, La Trobe University, La Trobe University

In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

In February 1852, 46-year-old Mary Anne Allen set off from Melbourne for the Mt Alexander (Castlemaine) diggings with her husband Reverend John Allen and their eight children, the youngest aged five.

Histories of the Victorian gold rushes often overlook women’s presence on the goldfields in 1852. Women, children and home, however, were always part of goldfields life.

Mary Anne Allen’s diary appears to have been written for publication. In it she observes life on the diggings, not through the lens of masculinity and mateship, but through family and home.

A perilous journey

Englishwoman Mary Anne and her family had arrived in Port Phillip before the gold rushes. They migrated in 1849 to deliver the word of God for Scottish evangelist and colonial enthusiast John Dunmore Lang. Yet two years later the family abandoned their congregation in search of gold, “dreaming of little beyond wealth and competency”.

On route to Mt Alexander, the family almost lost their dray over a ravine. Their son Frederick tried to “scotch the wheels” (likely wedging a stone or bar to stop them rolling) but to no avail.

“My little girl came running towards me”, wrote Mary Anne in her diary. “She said we expected father would have been killed but Fred’s hand was smashed and two of his fingers broken.” Disaster was averted, but it would be just the beginning of the family’s trials.

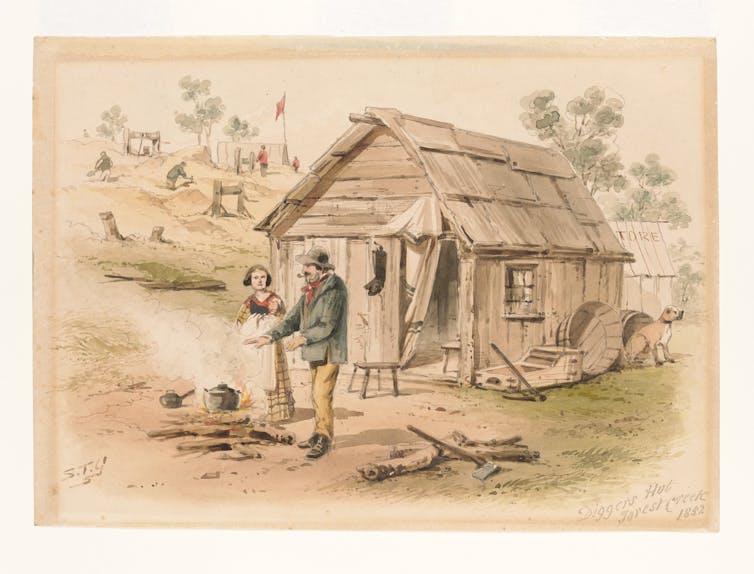

Most stories of the goldfields were told through the lens of mateship and masculinity. An early illustration by S. T. Gill.

State Library of Victoria

Most stories of the goldfields were told through the lens of mateship and masculinity. An early illustration by S. T. Gill.

State Library of Victoria

Next, four bushrangers bailed up a bullock driver ahead of them. The Allen family continued cautiously forward, one of her sons armed with a gun, the second with a hatchet, a third with a club. Mary Anne’s younger children inquired anxiously, “What will they do with you Mamma?” Fortunately, fate spared Mary Anne an answer.

Life in the clearings

Mary Anne found the new goldfields “remarkably picturesque and singularly beautiful”. The countryside was already home to miners’ mia-mias (based on Aboriginal dwellings) and hundreds of tents, scattered for miles through the still dense bush.

But clean drinking water was impossible to find. A German miner gave Mary Anne’s children a cup of water, milky with chalk. Another miner gave Mary Anne a loaded gun to help her protect any water they found. The family moved on to nearby Barker’s Creek, where there were fewer tents and more available water.

The Allen’s erected their tent and furnished it with handmade “bush bedsteads”: saplings driven into the ground and bed cases filled with dried leaves. Their table was topped with bark and the floor carpeted with the same. Mary Anne wrote that the bark decomposed rapidly in wet weather, producing an “exceedingly unpleasant” smell.

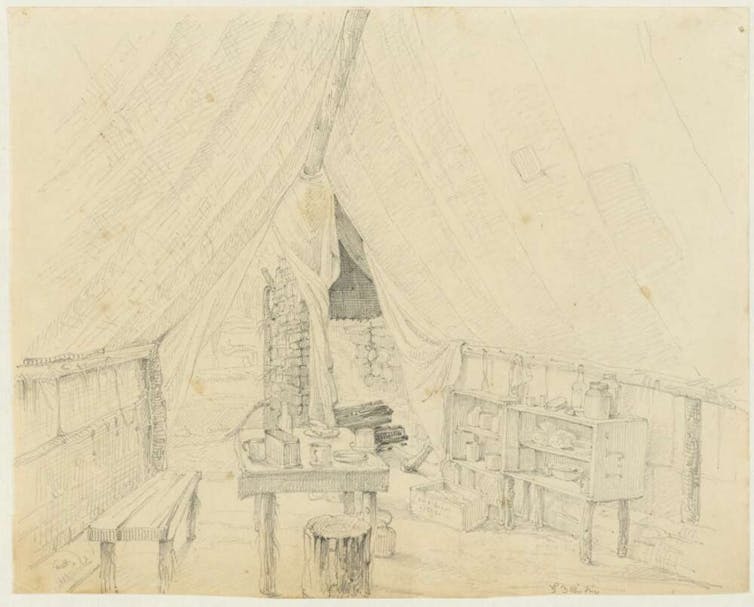

Henry Winkles, ‘Interior of a digger’s tent’, c.1853.

National Library of Australia

Henry Winkles, ‘Interior of a digger’s tent’, c.1853.

National Library of Australia

Many miners’ tents, she wrote, were lined with blankets inside and bullock hides externally to keep out the weather. Her sons built a stone fireplace with bark sides, which they topped with an old sugar cask. They put up a tarpaulin awning so the family could bake damper and roast meat without standing in the rain. Even with these precautions, mould covered everything.

Living with uncertainty

Families lived in fear of the dangers presented by mine shafts. The lesson was brought home for the Allen family as they watched a man trapped down a shaft. Then another man went in after him. The father of one of the men rushed forward and he too fell headlong into the mine. The whole party, Mary Anne noted disapprovingly, was the worse for “the influence of spirits”.

Bushfires were a frightening, yet entertaining, reality:

One small tree burnt through fell at our horses feet. We hastened onwards and when out of danger we sat and admired the grandeur of the scene.

At night, diggings glowed with fires outside every tent and lamps lit by candlewicks made from honeysuckle flowers soaked in oil. One night, as the family sat reading around their table, a gun was fired through their tent. The bullet landed on her son’s book: “So uncertain was life at Barker’s Creek”.

On the diggings, Sunday was not for religion but for domestic duties and domestic quarrels. Sometimes Mary Anne expected that “instant death would ensue from stabbing members of their own families”.

Canvas and bark tents smelled terrible when wet.

S. T. Gill/State Library of Victoria

Canvas and bark tents smelled terrible when wet.

S. T. Gill/State Library of Victoria

Read more: Emancipated wenches in gaudy jewellery: the liberating bling of the goldfields

Abrupt endings

Living next door to a sly grog tent, Mary Anne reported: “Drunkenness, fighting, profanity and robberies were every day occurrences”. Her diary ends abruptly, to cries of murder and an aborted gold robbery.

She did not record whether her family found gold. Historical documents reveal the family only stayed six months on the diggings. John did not return to the church until just before his death in 1861, by which time the couple had bought a number of properties in Melbourne.

My doctoral research is the first time Mary Anne’s diary has been written into goldfields history. Her manuscript is entitled Mrs Allen’s Trip to the Gold Fields, suggesting she intended it for publication. Now, almost 170 years later, we can read her observations as one of many women on the diggings in early 1852.

Read more: Friday essay: masters of the future or heirs of the past? Mining, history and Indigenous ownership

Authors: Katrina Dernelley, PhD Candidate in History, La Trobe University, La Trobe University