How can younger Australians decide about the AstraZeneca vaccine? A GP explains

- Written by Brett Montgomery, Senior Lecturer in General Practice, The University of Western Australia

It has been a wild week for public messaging about the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine — baffling both for the public and for general practitioners like me.

Just over two weeks ago, the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) advised the AstraZeneca vaccine was now preferred only for people over 60. The Pfizer vaccine was encouraged in those under 60, but this isn’t yet widely available.

Read more: Australians under 60 will no longer receive the AstraZeneca vaccine. So what's changed?

Prime Minister Scott Morrison sparked a controversy on Monday, saying ATAGI’s advice did not prohibit the vaccine in younger people. He invited people under 60 to chat to their GPs about it. This was reported as a “massive change” to the vaccine program.

His comments were rebuked by health officers and premiers.

Meanwhile, Health Minister Greg Hunt explained there had been “no change” to the medical advice.

For many, these disagreements were confusing.

Hunt is right, though: the ATAGI advice has remained the same since mid-June. The advice is careful and nuanced:

COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca can be used in adults aged under 60 years for whom Comirnaty [Pfizer] is not available, the benefits are likely to outweigh the risks for that individual and the person has made an informed decision based on an understanding of the risks and benefits.

Let’s dig into this sentence’s subtleties, and try to shed light rather than heat on the issue.

Three principles for decision-making

ATAGI’s sentence above contains three principles, all of which should be true if the AstraZeneca vaccine is to be used in a person under 60.

First, the Pfizer vaccine should be unavailable. This is the case for many people at the moment. Anecdotally, I’m told of waits of about three months for the Pfizer, if you can get an appointment at all. A surge in availability is promised, but not until October.

Second, the benefits of the AstraZeneca vaccine should outweigh the risks. This is tough, as risks and benefits can be hard to estimate.

The major (and well-known) risk of the AstraZeneca vaccine is an unusual clotting syndrome, which is rare, treatable, but sometimes fatal.

The benefits include prevention of COVID and its consequences, including hospitalisation and death.

The balance between risks and benefits depends on the person’s risk of being exposed to COVID (which might vary based on travel or occupation) and on their risk of bad outcomes (like death) should they get COVID.

Age seems the most important risk factor for these terrible outcomes, but other conditions appear important too, including heart disease, lung disease, high blood pressure, diabetes and cancer. (Though people under 60 with these conditions are eligible for Pfizer, at present they may be kept waiting.)

The risk of virus exposure depends greatly on how much COVID is present in our community. The less there is about, the less likely you’ll catch it. But this can change quickly and unpredictably, adding difficulty to decisions.

Third, the person receiving the vaccine needs to give their informed consent based on an understanding of these risks and benefits.

To give informed consent, you need to understand the risks and benefits.

CDC/Unsplash

To give informed consent, you need to understand the risks and benefits.

CDC/Unsplash

Informed consent

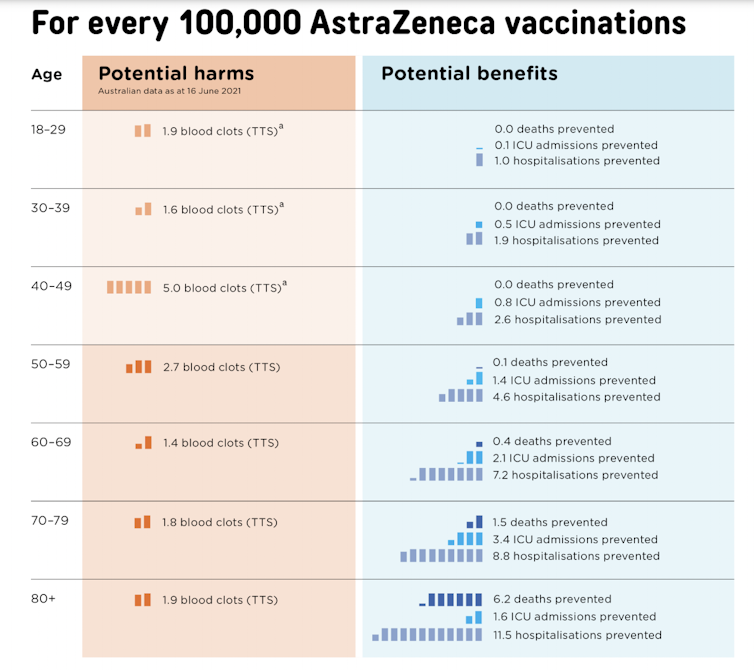

Handy decision aids help visualise some, but not all, of these risks. For example, this figure shows the trade-off between risks and benefits during a relatively mild outbreak, equivalent to Australia’s first COVID wave.

Screenshot from health.gov.au

In this setting, the benefits of vaccination don’t clearly outweigh the risks until people are over the age of 60. This is why ATAGI has used 60 as an age threshold for using the AstraZeneca vaccine.

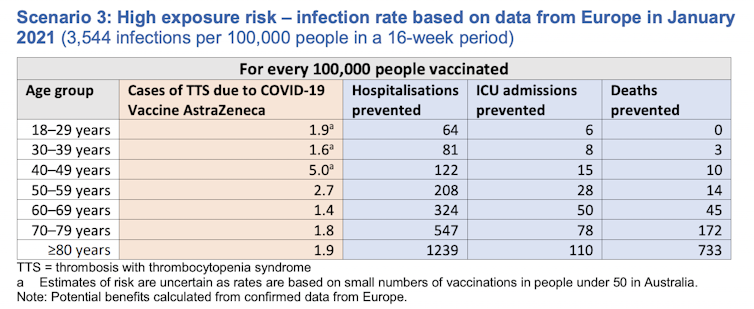

But if we had a severe outbreak, like in Europe last winter, the benefits of the vaccine would easily outweigh the risks, even in people from the age of 30.

Screenshot from health.gov.au

In this setting, the benefits of vaccination don’t clearly outweigh the risks until people are over the age of 60. This is why ATAGI has used 60 as an age threshold for using the AstraZeneca vaccine.

But if we had a severe outbreak, like in Europe last winter, the benefits of the vaccine would easily outweigh the risks, even in people from the age of 30.

Screenshot from health.gov.au

Individual decisions

These charts are helpful for thinking about how age and disease prevalence affect decisions. But they don’t include all relevant facts. For this, a discussion with a GP could be helpful — ideally a GP who knows you well.

ATAGI’s co-chair Christopher Blyth has recently clarified the AstraZeneca vaccine should only be used under 60 in “pressing” circumstances.

I can imagine such circumstances. For example, consider a 59 year-old with diabetes and heart disease who plans to travel to a country with many COVID cases. Here, I’d feel confident the benefits outweigh the risks.

However, imagine a 25 year-old with no underlying medical conditions, not travelling, and not working in a high-risk profession. Compared to the previous example, risks are similar, but benefits are fewer. It’d be hard to convince myself the benefits would outweigh the harms here — at least not while our COVID case numbers remain low.

Read more:

Under-40s can ask their GP for an AstraZeneca shot. What's changed? What are the risks? Are there benefits?

However, our case numbers are unlikely to stay low forever and if we wait for a big outbreak before vaccinating, immunity may arrive too late.

These are fraught decisions, full of ethical tensions. I want to respect my patient’s autonomy — and there’s a part of me that feels I should be able to vaccinate anyone if they are informed and want the vaccine. After all, many people take other, bigger risks elsewhere in their life.

And it’s admirable many younger Australians seeking vaccination are doing so not just for themselves but also to protect their community. But balanced with this, we need to try to minimise harm.

Screenshot from health.gov.au

Individual decisions

These charts are helpful for thinking about how age and disease prevalence affect decisions. But they don’t include all relevant facts. For this, a discussion with a GP could be helpful — ideally a GP who knows you well.

ATAGI’s co-chair Christopher Blyth has recently clarified the AstraZeneca vaccine should only be used under 60 in “pressing” circumstances.

I can imagine such circumstances. For example, consider a 59 year-old with diabetes and heart disease who plans to travel to a country with many COVID cases. Here, I’d feel confident the benefits outweigh the risks.

However, imagine a 25 year-old with no underlying medical conditions, not travelling, and not working in a high-risk profession. Compared to the previous example, risks are similar, but benefits are fewer. It’d be hard to convince myself the benefits would outweigh the harms here — at least not while our COVID case numbers remain low.

Read more:

Under-40s can ask their GP for an AstraZeneca shot. What's changed? What are the risks? Are there benefits?

However, our case numbers are unlikely to stay low forever and if we wait for a big outbreak before vaccinating, immunity may arrive too late.

These are fraught decisions, full of ethical tensions. I want to respect my patient’s autonomy — and there’s a part of me that feels I should be able to vaccinate anyone if they are informed and want the vaccine. After all, many people take other, bigger risks elsewhere in their life.

And it’s admirable many younger Australians seeking vaccination are doing so not just for themselves but also to protect their community. But balanced with this, we need to try to minimise harm.

The risks are small but real, and need to be balanced with the benefits.

Shutterstock

Under 60 and still keen for a vaccine?

If you want to be vaccinated and are under 60, and Pfizer is unavailable, you could speak to your GP — especially if your circumstances put you at special risk.

I think it is best to do this in a special consultation rather than squeezing it into an immunisation clinic time slot. Because our vaccines come in multidose vials, most practices run quite rapid-fire vaccination clinics, allowing only a few minutes for each person. Such clinics are workable for uncontroversial vaccine decisions in people over 60, but mightn’t allow enough time for complex decisions with younger people.

By working with your GP, I hope you’ll feel you can arrive at the decision best suited to your circumstances and values.

The risks are small but real, and need to be balanced with the benefits.

Shutterstock

Under 60 and still keen for a vaccine?

If you want to be vaccinated and are under 60, and Pfizer is unavailable, you could speak to your GP — especially if your circumstances put you at special risk.

I think it is best to do this in a special consultation rather than squeezing it into an immunisation clinic time slot. Because our vaccines come in multidose vials, most practices run quite rapid-fire vaccination clinics, allowing only a few minutes for each person. Such clinics are workable for uncontroversial vaccine decisions in people over 60, but mightn’t allow enough time for complex decisions with younger people.

By working with your GP, I hope you’ll feel you can arrive at the decision best suited to your circumstances and values.

Authors: Brett Montgomery, Senior Lecturer in General Practice, The University of Western Australia