China's Tiangong space station: what it is, what it's for, and how to see it

- Written by Paulo de Souza, Professor, Griffith University

China’s space program is making impressive progress. The country only launched its first crewed flight in 2003, more than 40 years after the Soviet Union’s Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space. China’s first Mars mission was in 2020, half a century after the US Mariner 9 probe flew past the red planet.

But the rising Asian superpower is catching up fast: flying missions to the Moon and Mars; launching heavy-lift rockets; building a new space telescope set to fly in 2024; and, most recently, putting the first piece of the Tiangong space station (the name means Heavenly Palace) into orbit.

What is the Tiangong space station?

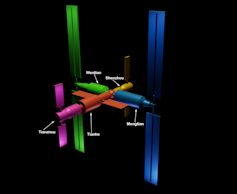

Tiangong is the successor to China’s Tiangong-1 and Tiangong-2 space laboratories, launched in 2011 and 2016, respectively. It will be built on a modular design, similar to the International Space Station operated by the United States, Russia, Japan, Canada and the European Space Agency. When complete, Tiangong will consist of a core module attached to two laboratories with a combined weight of nearly 70 tonnes.

The core capsule, named Tianhe (Harmony of Heavens), is about the size of a bus. Containing life support and control systems, this core will be the station’s living quarters. At 22.5 tonnes, the Tianhe capsule is the biggest and heaviest spacecraft China has ever constructed.

The Tianhe module will form the core of the space station, with other modules to be added later to increase the size of the station and make more experiments possible.

Saggitarius A / Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

The Tianhe module will form the core of the space station, with other modules to be added later to increase the size of the station and make more experiments possible.

Saggitarius A / Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

The capsule will be central to the space station’s future operations. In 2022, two slightly smaller modules are expected to join Tianhe to extend the space station and make it possible to carry out various scientific and technological experiments. Ultimately, the station will include 14 internal experiment racks and 50 external ports for studies of the space environment.

Tianhe will be just one-fifth the size of the International Space Station, and will host up to three crew members at a time. The first three “taikonauts” (as Chinese astronauts are often known) are expected to take up residence in June.

Read more: How to live in space: what we've learned from 20 years of the International Space Station

A troubled launch

Tianhe was launched from China’s Hainan island on April 29 aboard a Long March 5B rocket.

These rockets have one core stage and four boosters, each of which is nearly 28 metres tall - the height of a nine-storey building - and more than 3 metres wide. The Long March 5B weighs about 850 tonnes when fully fuelled, and can lift a 25-tonne payload into low Earth orbit.

A crowd gathers to watch the launch of the Tianhe module of the Chinese space station on April 29 2021.

Koki Kataoka / AP

A crowd gathers to watch the launch of the Tianhe module of the Chinese space station on April 29 2021.

Koki Kataoka / AP

During the Tianhe launch, the gigantic core stage of the rocket – weighing around 20 tonnes – spun out of control, eventually splashing down more than a week later in the Indian Ocean. The absence of a control system for the return of the rocket to Earth has raised criticism from the international community.

Read more: A giant piece of space junk is hurtling towards Earth. Here's how worried you should be

However, these rockets are a key element of China’s short-term ambitions in space. They are planned to be used to deliver modules and crew to Tiangong, as well as launching exploratory probes to the Moon and eventually Mars.

Despite leaving behind an enormous hunk of space junk, Tianhe made it safely to orbit. An hour and 13 minutes after launch, its solar panels started operating and the module powered up.

Completion and future

Tianhe is now sitting in low-Earth orbit (about 400km above the ground), waiting for the first of the ten scheduled supply flights over the next 18 months that it will take to complete the Tiangong station.

A pair of experiment modules named Wentian (Quest for Heavens) and Mengtian (Dreaming of Heavens) are planned for launch in 2022. Although the station is being built by China alone, nine other nations have already signed on to fly experiments aboard Tiangong.

How to see the Tiangong space station

Tianhe is already visible with the naked eye, if you know where and when to look.

A video shot from New Zealand shows the tumbling chunk of rocket from Tianhe’s launch, followed by the bright dot of the space station module itself.To find out when the space station might be visible from where you are, you can check websites such as n2yo.com, which show you the station’s current location and its predicted path for the next 10 days. Note that these predictions are based on models that can change quite quickly, because the space station is slowly falling in its orbit and periodically boosts itself back up to higher altitudes.

The station orbits Earth every 91 minutes. Once you find the time of the station’s next pass over your location (at night - you won’t be able to see it in the daytime), check the direction it will be coming from, find yourself a dark spot away from bright lights, and look out for a tiny, fast-moving spark of light trailing across the heavens.

Authors: Paulo de Souza, Professor, Griffith University