If I could go anywhere: Florence's San Marco Museum, where mystical faith and classical knowledge meet

- Written by Joanna Mendelssohn, Principal Fellow (Hon), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, The University of Melbourne

In this series we pay tribute to the art we wish could visit — and hope to see once travel restrictions are lifted.

In 1981, I visited the San Marco Museum on my very first visit to Italy. I had been totally overwhelmed by the volume and concentration of great art in the nearby Uffizi Gallery. But in this much smaller building, the past started to make sense. An elegant structure, the San Marco Museum almost appeared to be in conversation with the mystical tradition of 15th century painter Fra Angelico’s frescoes within its walls. Some 35 years later, when I returned to Florence, I was pleased to see that my memories had not deceived me.

Now, at a time when travel to Europe is impossible, San Marco is the place I would most like to see again — for its architecture, its art and for the place it holds in history.

Once a convent

The Convent of San Marco, consecrated in 1443, was commissioned by banker and Grand Duke of Tuscany Cosimo de’ Medici and designed by Michelozzi, an architect who had trained as a sculptor under Donatello.

The building is exquisite in the way its classical proportions work in harmony with ecclesiastical traditions. Frescoes decorate the elegant arched cloisters enclosing the gardens. On the first floor visitors see the perfectly proportioned library of Cosimo de’ Medici, the first public library of the Italian Renaissance, crucial to the rediscovery of classical knowledge.

The first phase in the modern restoration of Annunciation was carefully cleaning dirt and pollutants from the pictorial surface.Fra Angelico was, with his assistants, responsible for most of the paintings. He may have painted with a growing awareness of geometric perspective, but he was supremely uninterested in the revival of classical imagery and form.

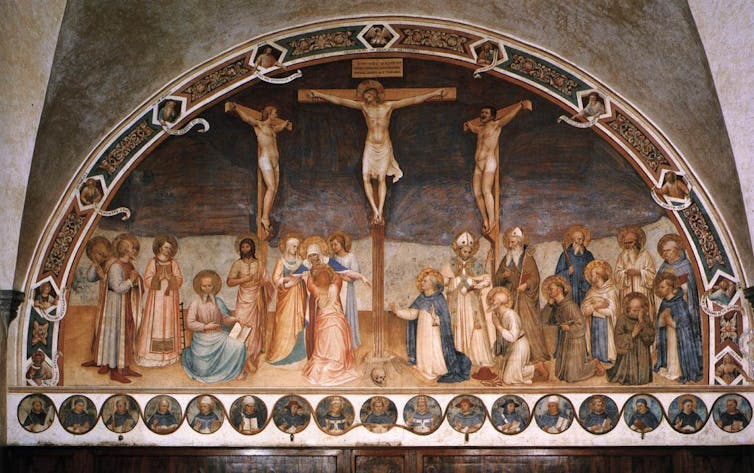

His art in both subject and form is based on the Liturgy, and was always an expression of his faith. There are scenes from the life of Christ, with many crucifixion paintings as well as saints including St Thomas Aquinas and St Dominic, the order’s founder. The magnificent Crucifixion and Saints fills the end wall of the Chapter House, where the monks once met as a congregation.

Fra Angelico’s Crucifixion and Saints (1441–42), Basilica di San Marco, Florence, Italy.

Wikiart

Fra Angelico’s Crucifixion and Saints (1441–42), Basilica di San Marco, Florence, Italy.

Wikiart

The private lives of monks

The great pleasure of San Marco is the way gives visual insights into the private meditative life the monks.

At the top of the stairs on the way to the dormitory the visitor is greeted with Fra Angelico’s masterpiece Annunciation. It seems almost a contradiction that the monks, devoted to a life of austerity should see such overwhelming beauty every day.

A monk’s cell and fresco inside the San Marco Museum.

Shutterstock

A monk’s cell and fresco inside the San Marco Museum.

Shutterstock

The monk’s cells make San Marco even more special. Many of them are decorated with frescoes.

Cosimo de’ Medici was sufficiently involved in the monastery’s life that he had his own cell (naturally double the size of the monk’s cells) decorated with a magnificent Adoration of the Magi.

But the cell that most intrigues me does not have a fresco. Its plain walls are hung with a single painting captioned, “Ignoto fiorentino della fine del sec XV/Supplizio del Savonarola in piazza della Signoria/Dipinto su tavola”. This translates as: Unknown Florentine of the end of the 15th century/The Torture of Savonarola in the Piazza della Signoria/Painted on wood.

Hanging and burning of Girolamo Savonarola in Florence, 1498. Artist unknown.

Wikiart

Hanging and burning of Girolamo Savonarola in Florence, 1498. Artist unknown.

Wikiart

Read more: Why weren't there any great women artists? In gratitude to Linda Nochlin

A fiery end

This is the cell of Girolamo Savonarola, Prior of San Marco. He warned Florentines the apocalypse was coming, and urged them to free themselves from fleshly sins by burning artworks, books, dresses and cosmetics in the original Bonfire of the Vanities.

But the friar went from burning heretics to being convicted as one — he was tortured, burnt and executed in 1498.

This painting is not a great work of art. It is a record rather than a celebration. White-clad monks are escorted to their doom while the citizens of Florence carry on their business with apparent indifference. The only hint of partisanship by either the artist or those who commissioned the work are the angels who appear ready to celebrate the arrival of a new saint. As it dates from the approximate time of Savonarola’s execution it was probably prudent to make this record portable (and anonymous) so it could be easily hidden from those who had orchestrated his death.

One artist who was profoundly influenced by Savonarola’s teaching was Sandro Botticelli, best known for the Birth of Venus, who destroyed some of his earlier paintings at friar Savonarola’s urging.

In 1494, the artist painted The Calumny of Apelles in response to the way rumour and innuendo was being used to discredit Savonarola, whose ideas were a prelude to the rise of Protestant fundamentalism. After this work, Botticelli restricted his works to religious subjects in paintings that owe a great deal to the aesthetic of Fra Angelico.

The conjunction of these two great opposing traditions of ideas and art — mystical faith and classical knowledge — are here in one building. San Marco Museum is the visual and material representation of a debate that has lasted over 500 years. It is also incredibly beautiful. For that reason alone I need to see it again.

Read more: Globalisation was rife in the 16th century – clues from Renaissance paintings

Authors: Joanna Mendelssohn, Principal Fellow (Hon), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, The University of Melbourne