What is suffragette white? The colour has a 110-year history as a protest tool

- Written by Michelle Staff, PhD Candidate, Australian National University

“Suffragette white” is proving to be a popular fashion choice for women who want to make a statement. Most recently, former Australia Post CEO Christine Holgate donned a white jacket in her appearance before a Senate inquiry into her controversial departure from the organisation.

Christine Holgate appears in white.

AAP Image/Mick Tsikas

Christine Holgate appears in white.

AAP Image/Mick Tsikas

Her sartorial choice formed part of the “Wear White 2 Unite” campaign, which encouraged people to sport the colour in support of Holgate and call for an end to workplace bullying.

In doing this, Holgate, like Brittany Higgins last month at the Canberra March4Justice, is building on a trend in which women are wearing white clothing — and often referencing suffrage history — to draw attention to gender inequity today.

Deeds not words

The term “suffragette” is sometimes mistakenly used to refer to all those who campaigned for women’s voting rights. But it was actually a label applied to a specific group of women — initially in a derogatory sense.

The women’s suffrage movement in Britain took off during the 1860s. By the turn of the 20th century, women still did not have the vote.

Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Mabel Tuke and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, 17th June 1911, marching at the head of the Prisoners’ Pageant at the Coronation Procession.

Digital image copyright Museum of London

Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Mabel Tuke and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, 17th June 1911, marching at the head of the Prisoners’ Pageant at the Coronation Procession.

Digital image copyright Museum of London

This led Emmeline Pankhurst to establish the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. Her group of primarily white women believed militancy was the only way they could achieve change, living by the motto “deeds not words”.

The British press mockingly labelled these women “suffragettes”, adding the diminutive suffix “-ette” in an attempt to de-legitimise them. But Pankhurst’s group was not deterred. It reclaimed the term, eliminating the element of ridicule and rebranding it as “a name of highest honour”.

One of the WSPU teams that drew the carriage of released prisoners away from Holloway in 1908.

Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science

One of the WSPU teams that drew the carriage of released prisoners away from Holloway in 1908.

Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science

Her group’s dramatic actions – from disrupting meetings to damaging public property – cemented their place in the history of women’s suffrage.

Purity, dignity and hope

Early 20th century suffrage campaigns relied heavily on spectacle and pageantry, using striking visual imagery and mass gatherings to garner the attention of the press and the wider public.

Many suffrage organisations adopted colours to symbolise their agenda. In Britain, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies used red and white in their banners, later adding green. The WSPU chose white, purple and green: white for purity, purple for dignity and green for hope.

An original Women’s Social and Political Union postcard album, with the circular purple, white and green WSPU motif printed on the front.

Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science

An original Women’s Social and Political Union postcard album, with the circular purple, white and green WSPU motif printed on the front.

Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science

Suffragette white was first donned en masse in June 1908 on Women’s Sunday, the first “monster meeting” hosted by the WSPU in London’s Hyde Park. The 30,000 participants were encouraged to wear white, accessorised with touches of purple and green.

Ahead of the march, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence’s newspaper Votes for Women explained:

the effect will be a magnificent moving colour scheme never before seen in London’s streets.

White fabric was relatively affordable, which meant women of different backgrounds could participate. The colour’s association with purity also helped those involved present themselves as respectable, dignified women.

The Suffragette Coronation Procession through central London, 17 June, 1911.

Digital image copyright Museum of London

The Suffragette Coronation Procession through central London, 17 June, 1911.

Digital image copyright Museum of London

Suffragette white became a mainstay of the WSPU’s demonstrations. In 1911, women who had been imprisoned for militancy were among those who marched in white in the Women’s Coronation Procession.

The Australian suffragist Vida Goldstein, wearing a white dress, famously headed the Australian contingent.

Goldstein later brought the WSPU’s colours to Australia in her campaigns for a parliamentary seat.

Read more: Friday essay: Sex, power and anger — a history of feminist protests in Australia

Two years later in 1913, members of the WSPU wore white in a funeral procession for their colleague Emily Wilding Davison, who died under the hooves of the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby.

American suffragists soon picked up this tactic, influenced by the British suffragettes as well as by the temperance movement’s use of white ribbons.

Cities like Washington D.C. witnessed similar scenes of women in white dresses marching through the streets, making striking material for photographers. Contemporary black women — who were excluded from the suffrage movement in many ways — used the colour in their protests against racial violence, too.

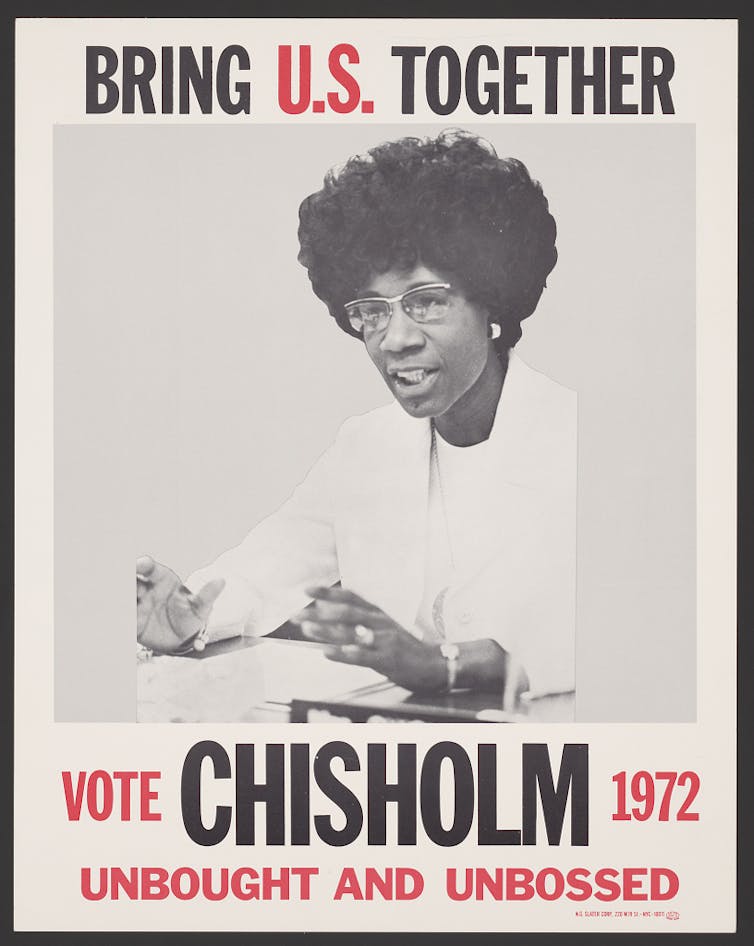

Fifty years after Black American women wore white in protest marches, white suits became a calling card of Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm.

Library of Congress

Fifty years after Black American women wore white in protest marches, white suits became a calling card of Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm.

Library of Congress

Feminist solidarity

The modern trend towards white has had particular traction in the US.

In 2019, Donald Trump faced a sea of suffragette white at his State of the Union address. Last year, Kamala Harris wore a white pantsuit to deliver her remarks as vice president-elect.

Closer to home, at the March4Justice rally in Canberra, Brittany Higgins made a surprise appearance in a white outfit, standing in contrast to the funereal black worn by attendees.

Brittany Higgins arrives to address the Women’s March 4 Justice in Canberra, Monday, March 15, 2021.

AAP Image/Lukas Coch

Brittany Higgins arrives to address the Women’s March 4 Justice in Canberra, Monday, March 15, 2021.

AAP Image/Lukas Coch

By wearing white, these women — either consciously or not — are building connections with their feminist forebears across the Anglosphere. At times this can flatten the complex history of women’s suffrage. It is important to remember it was primarily white, middle-class women who led these suffrage movements, often to the exclusion of women of colour and others.

In drawing on their feminist genealogy, women today need to acknowledge the limitations of feminisms past and present — and not simply celebrate and reproduce the attitudes of over a hundred years ago.

At the same time, wearing suffragette white is a powerful and highly symbolic gesture that reminds us just how long women have been fighting.

By establishing a sense of feminist solidarity across time and space, this move can also generate inspiration and energy and attract media attention. Women of colour’s choice to wear white can be read as a way of asserting their place within a movement from which they have historically been (and continue to be) excluded — and honouring women of colour who have come before them.

Democratic members of Congress, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, wore white to Donald Trump’s 2019 State of the Union.

AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite

Democratic members of Congress, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, wore white to Donald Trump’s 2019 State of the Union.

AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite

Like the suffragettes of the early 20th century, women today are showing the power of visual spectacle to grab the public’s attention. Whether this will, in turn, lead to real change remains to be seen.

Authors: Michelle Staff, PhD Candidate, Australian National University