How will our bodies be put back together? What about those eaten by cannibals? A brief history of Christian resurrection beliefs

- Written by Philip C. Almond, Emeritus Professor in the History of Religious Thought, The University of Queensland

Easter celebrates the Christian belief that Jesus Christ rose from the dead. In so doing, he overcame sin and death on behalf of all of us. The resurrection of Jesus was a guarantee that, for those who believed in him, they too would do the same. As St. Paul put it, “He who raised Christ from the dead will give life to your mortal bodies also”.

That said, the resurrected body of Jesus was a very ambiguous one. He ate fish and bread, but he could also pass through closed doors. Similarly, there has always been an uncertainty about the nature of our resurrection bodies.

By the end of the second century, Christianity had absorbed the Greek tradition of the immortality of the soul. From that time on, it viewed the human person as consisting of an immortal soul and a mortal body.

This meant that, immediately after death, the individual soul continued its existence. It also meant at the end of history, the individual body would rise from the dead and be reunited with its soul. God would then judge it as worthy of eternal happiness in heaven or eternal punishment in hell.

Christianity shared with Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and later Islam, a belief in the final resurrection of the body.

Luca Signorelli, Resurrection of the Flesh, a fresco painted between 1499 and 1502.

Wikimedia Commons

Luca Signorelli, Resurrection of the Flesh, a fresco painted between 1499 and 1502.

Wikimedia Commons

Read more: 5 things to know about the traditional Christian doctrine of hell

What sort of bodies?

What will resurrected bodies be like? Saint Augustine in his work The City of God gave us some clues early in the fifth century. They will be physical bodies but animated by an immortal soul. They will appear to be about 30 years old, the age that Christ reached.

Men will arise in male bodies and women in female bodies. But there will be no sexual desire and hence no marriages in heaven. The “flesh” will serve the “spirit” and not the reverse as happens in the present life.

Critics then, like critics now, thought it a ridiculous idea and panned it mercilessly. Even though Augustine thought the critics were being frivolous, he attempted to give serious answers to their questions. Will aborted foetuses rise? What size will they be? What will the bodies of monstrous births, the disfigured, and the deformed be like? What will be the fate of those devoured by beasts, consumed by fire, drowned, or eaten by cannibals?

By the 13th century, these questions had become matters of serious philosophical discussion within Christianity and not merely responses to critics of it. Thomas Aquinas, the greatest philosopher of Roman Catholicism, for example, picked up where Augustine left off.

On the day of resurrection, he believed, bodies will have the same gender and the same organs as when they were alive. But they won’t have the same uses because there will be no desire to eat, drink, or have sex.

Therefore, there will be no need for food, clothing, transportation, or medicine. There will be no need for heavenly plants nor (pet or meat lovers read no further!) animals. Those in hell would have bodies suitable to their character — ugly, sluggish, black, gross, and capable of suffering.

Read more:

Friday essay: what might heaven be like?

But what about the science?

By the 17th century, the new sciences were adding fresh answers to a key problem. How would all the dispersed bits of people get back together? For example, Robert Boyle, the father of modern chemistry, worried about bodies that were eaten by animals, fish or cannibals.

Men will arise in male bodies and women in female bodies. But there will be no sexual desire and hence no marriages in heaven. The “flesh” will serve the “spirit” and not the reverse as happens in the present life.

Critics then, like critics now, thought it a ridiculous idea and panned it mercilessly. Even though Augustine thought the critics were being frivolous, he attempted to give serious answers to their questions. Will aborted foetuses rise? What size will they be? What will the bodies of monstrous births, the disfigured, and the deformed be like? What will be the fate of those devoured by beasts, consumed by fire, drowned, or eaten by cannibals?

By the 13th century, these questions had become matters of serious philosophical discussion within Christianity and not merely responses to critics of it. Thomas Aquinas, the greatest philosopher of Roman Catholicism, for example, picked up where Augustine left off.

On the day of resurrection, he believed, bodies will have the same gender and the same organs as when they were alive. But they won’t have the same uses because there will be no desire to eat, drink, or have sex.

Therefore, there will be no need for food, clothing, transportation, or medicine. There will be no need for heavenly plants nor (pet or meat lovers read no further!) animals. Those in hell would have bodies suitable to their character — ugly, sluggish, black, gross, and capable of suffering.

Read more:

Friday essay: what might heaven be like?

But what about the science?

By the 17th century, the new sciences were adding fresh answers to a key problem. How would all the dispersed bits of people get back together? For example, Robert Boyle, the father of modern chemistry, worried about bodies that were eaten by animals, fish or cannibals.

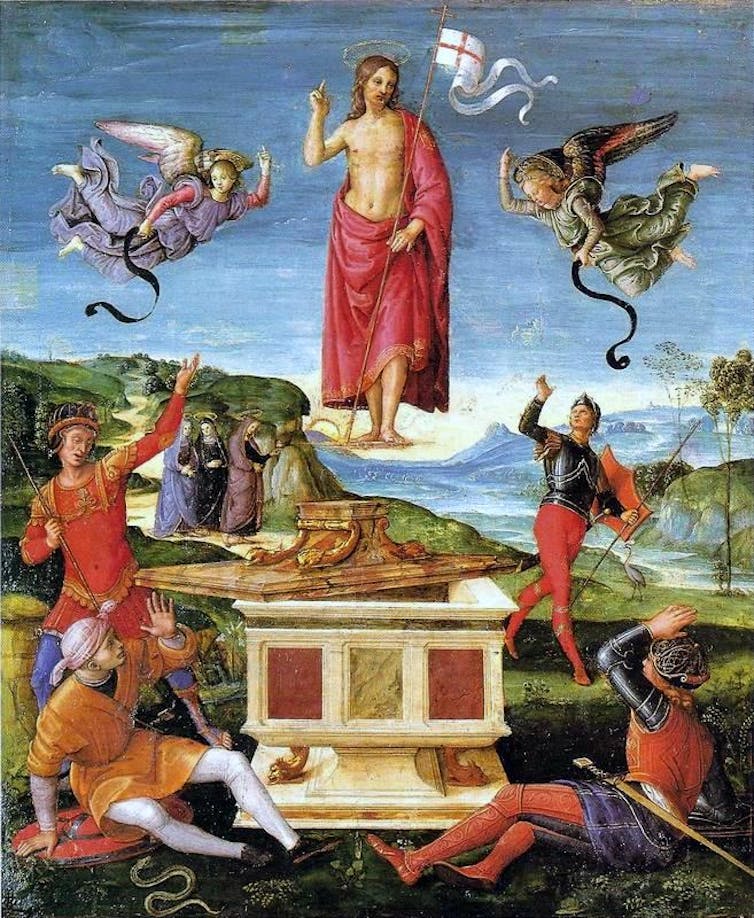

Raphael, The Resurrection of Jesus Christ (Kinnaird Resurrection), from 1499 to 1502.

Wikimedia Commons

At least a tiny bit of us, Boyle suggested, will be able to be retrieved from the bodies of animals, sharks, or cannibals — enough for God to work with. Moreover, his own chemical experiments on the long-lasting texture of bones assured him they would still be around on resurrection day. In the end, however, he like many others, was forced to fall back on God’s miraculous powers to get all of our bits and pieces back into one piece.

Vast amounts of theological ink were spilt on the attempt to defend what, at the end of the day, was really rationally indefensible. It is no surprise that, as the feasibility of the miraculous disappeared in the 18th century, so rational defences of the resurrection of the physical body disappeared from intellectual history. They were buried in a forgotten and unmarked theological grave.

These days, at least to more liberal Christians, the resurrection of the body remains a matter of faith rather than reason. It is pretty much ignored. The afterlife in general tends to be thought of as the survival of a spirit immediately after death or even only as a brief period of time in the memories of those still alive.

But whatever Christians believe about our resurrection body, they still believe Jesus rose physically, or perhaps spiritually, from the dead. It is a life and a death that continues to influence 2.3 billion people throughout the world.

Raphael, The Resurrection of Jesus Christ (Kinnaird Resurrection), from 1499 to 1502.

Wikimedia Commons

At least a tiny bit of us, Boyle suggested, will be able to be retrieved from the bodies of animals, sharks, or cannibals — enough for God to work with. Moreover, his own chemical experiments on the long-lasting texture of bones assured him they would still be around on resurrection day. In the end, however, he like many others, was forced to fall back on God’s miraculous powers to get all of our bits and pieces back into one piece.

Vast amounts of theological ink were spilt on the attempt to defend what, at the end of the day, was really rationally indefensible. It is no surprise that, as the feasibility of the miraculous disappeared in the 18th century, so rational defences of the resurrection of the physical body disappeared from intellectual history. They were buried in a forgotten and unmarked theological grave.

These days, at least to more liberal Christians, the resurrection of the body remains a matter of faith rather than reason. It is pretty much ignored. The afterlife in general tends to be thought of as the survival of a spirit immediately after death or even only as a brief period of time in the memories of those still alive.

But whatever Christians believe about our resurrection body, they still believe Jesus rose physically, or perhaps spiritually, from the dead. It is a life and a death that continues to influence 2.3 billion people throughout the world.

Authors: Philip C. Almond, Emeritus Professor in the History of Religious Thought, The University of Queensland