We can't seem to get enough of the Impressionists but can we move on from the sanitised version?

- Written by Elisabeth Findlay, Director of Queensland College of Art, Griffith University

Barely a year goes by on the Australian art calendar without the announcement of a major Impressionist exhibition. The latest is the National Gallery of Victoria’s “international exclusive show”, French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

The NGV’s is the next instalment in a series of recent Impressionist exhibitions, including Monet: Impression Sunrise (National Gallery of Australia, 2019) and Colours of Impressionism: Masterpieces from the Musée d’Orsay (Art Gallery of South Australia, 2018).

The global popularity of Impressionism can be traced back to 1886 when the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel mounted an exhibition of 300 Impressionist works in New York. Attracting widespread acclaim, it was a turning point in public awareness of the art movement.

The NGV announcement includes phrases such as “artistic energy and intellectual dynamism”, “radical practitioners” and a “breathtaking display”. But such cliche and hyperbole belies the more interesting realities of a divided group of artists striving to capture the complexities of the emerging modern world around them.

A romanticised story

At the heart of the popularity of Impressionism is a romanticised story of a group of young artists battling against the conservatism of the dominant French Salon. They are repeatedly presented as a passionate collective who embraced plein air painting, capturing nature with unprecedented freshness.

Impressionist exhibitions almost invariably perpetuate the notion of the male artist as a genius. An aura surrounds artists such as Monet, Renoir and Degas. They are repeatedly viewed as heroic radicals who shunned the establishment, rallying together to champion a new form of art.

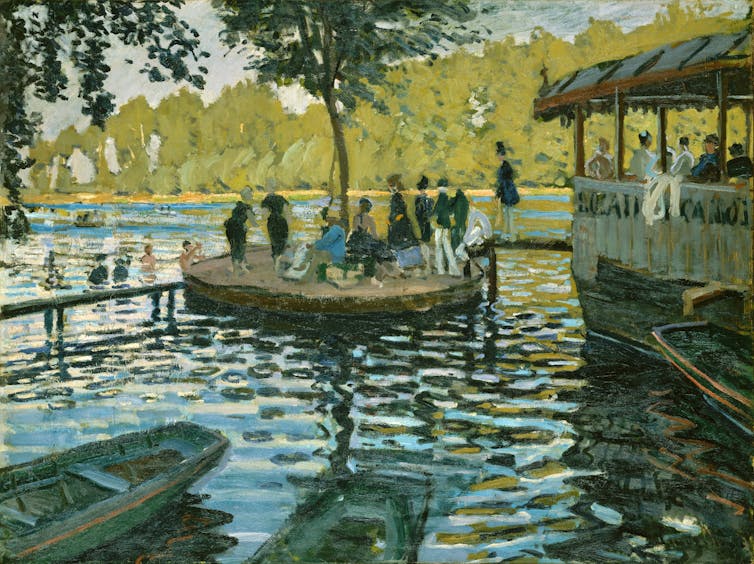

For decades, Monet in particular, has been singled out for praise. From his pioneering work at La Grenouillère to his final days at Giverny, Monet is applauded for abandoning the studio and immersing himself in the landscape. His paintings have become the paragon of the Impressionists’ ability to authentically capture the world around them.

Claude Monet, La Grenouillère, 1869.

Wikimedia Commons

Claude Monet, La Grenouillère, 1869.

Wikimedia Commons

This romanticised story of visionary artists working in nature is echoed in the stories of Impressionism beyond France. By the late 19th century local variants of Impressionism had spread to places such as America and Australia. She-Oak and Sunlight: Australian Impressionism will also be held at the NGV this year, presenting the work of leading exponents of Australian Impressionism. Into the 20th century, Impressionist techniques continued to be embraced in countries beyond France, including Japan and China.

Read more: Art Gallery SA goes back to Impressionism's colourful roots with masterpieces from Musee d'Orsay

Impressionist paintings readily lend themselves to merchandising, with their work reproduced on a vast array of mementos, including postcards, posters, mugs, magnets, scarves, jigsaw puzzles and even umbrellas. For galleries, the large crowds and their willingness to spend on such items are a winning blockbuster formula. Critics such as Meta Knol have lamented our addiction to the blockbuster but such a successful model is difficult to abandon.

Division

However, the version of Impressionism that accompanies most blockbusters is highly sanitised. In truth, the artists were not the united group of popular imagination.

Degas was a particularly divisive figure. He was strident in his view that no-one in the group should exhibit with the conservative Salon, which had rejected and ridiculed them. This was an abiding source of tension.

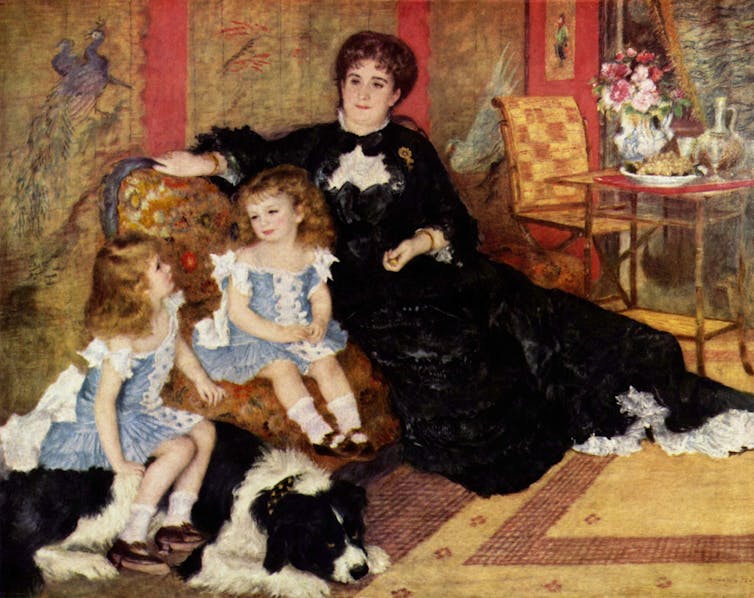

In 1879 Renoir exhibited Madame Charpentier with her Children at the Salon, which enraged Degas. A further feud broke out when Monet followed Renoir’s example and submitted Seine at Lavacourt to the Salon. While usually portrayed as radicals, clearly Renoir and Monet were happy to court official recognition.

Pierre Auguste Renoir, Mme. Charpentier and Her Children , 1878.

Wikimedia Commons

Pierre Auguste Renoir, Mme. Charpentier and Her Children , 1878.

Wikimedia Commons

Pissaro and Degas argued that Monet should be thrown out of the group and consequently Monet, Renoir and Sisley did not exhibit in the fifth exhibition in 1880. As the bickering escalated, Durand-Ruel increasingly resorted to solo shows. By the final Impressionist exhibition in 1886 there was considerable acrimony within the group with Monet also rejecting Seurat’s Neo-Impressionism and his scientific application of optical principles.

The familiar blockbuster tropes also mask the reality that many Impressionists painted disturbing observations of human relationships and social division. Art historian T. J. Clarke in The Painting of Modern Life demonstrates that urbanisation and political instability in late 19th century France provides a much richer context to appreciate Impressionism than stories of individual geniuses capturing a fleeting moment.

For the Impressionists, places of leisure were ideal for observing human interaction. Degas, in particular, did not shy away from presenting the undercurrents of urban life. In Women on a Café Terrace in the Evening (1877), for instance, he depicts a group of prostitutes. The woman in the middle is biting her thumb. Often interpreted as a simple sign of her boredom, art historian Hollis Clayson suggests this gesture references particular sexual activities.

Renoir’s Dance At Bougival, 1883.

Wikimedia Commons

Renoir’s Dance At Bougival, 1883.

Wikimedia Commons

In Dance at Bougival, one of the major paintings in the forthcoming NGV French Impressionism exhibition, Renoir depicts a couple dancing in the new open-air cafes.

On one level this is a simple scene of frivolity but a closer look reveals something more menacing at play. The woman is looking away from the boatman with her eyes cast down, while he leans into her with his face obscured by his straw hat. Their flushed cheeks and the way he pulls her towards him invites an uneasy contemplation of their relationship.

The discarded bouquet and the burnt matches add to the sense that something is awry. Renoir would have been very familiar with the use of such items as symbols of fallen virtue.

Tension

Even in a portrait as endearing as Mary Cassatt’s Ellen Mary in a White Coat — also among the paintings coming to Melbourne — there is a tension. Feminist art historians such as Griselda Pollock have argued there are radical undercurrents to such domestic images.

Read more: The National Gallery is erasing women from the history of art

Mary Cassatt, Ellen Mary Cassatt In A White Coat, 1896.

Wikimedia Commons

Mary Cassatt, Ellen Mary Cassatt In A White Coat, 1896.

Wikimedia Commons

As a single woman, Cassatt did not have the opportunity to paint a scene such as Renoir’s Dance at Bougival. Her gender and class denied her access to the open-air cafes.

Cassatt’s images of domesticity therefore reflect her confinement. The recurring imagery of little girls also reveals her concern for the next generation of women. The serious faced Ellen, who is swamped by her bonnet and coat, holds firmly to the chair as she looks to a point in the distance in this psychologically complex portrait.

Impressionist exhibitions will continue to delight large audiences. However, it is unfortunate that the anodyne story of the movement dominates.

Authors: Elisabeth Findlay, Director of Queensland College of Art, Griffith University