No change at the top for university leaders as men outnumber women 3 to 1

- Written by Marcia Devlin, Adjunct Professor, Victoria University

Australian university leaders are nearly three times more likely to be a man than a woman.

Of 37 public university chancellors, just 10 are women (27%) and 27 (73%) are men. It’s exactly the same for vice-chancellors: 10 are women and 27 are men.

Together, this means men hold 54 of the 74 top jobs in Australian higher education.

Read more: Most of Australia's uni leaders are white, male and grey. This lack of diversity could be a handicap

Last year presented a big opportunity for progress towards gender equity among university leaders. During 2020, vice-chancellors at 15 of Australia’s 37 public universities either announced their departure from the role, or actually left. This move of 41% of the vice-chancellors in a single year provided the best opportunity for improving gender equity in living memory.

Unfortunately, Australian university councils, which appoint vice-chancellors, did not take up the opportunity. The gender ratio didn’t change at all.

To date, women have been appointed in just four of the 15 (27%) interim or ongoing replacements made. Two of these four women moved from one vice-chancellor position to another. In 11 of the 15 announced vice-chancellor replacements – 73% of cases – a man won the role.

Men also dominate the upper levels of Australian academia. The latest available figures (from 2019) show:

86% more men than women at associate professor and professor levels D and E (10,363 men, 5,562 women)

11% more men than women at senior lecturer level C (6,355 men, 5,724 women)

25% more women than men at lecturer level B (7,428 men, 9,253 women)

15% more women than men at associate lecturer level A (4,426 men and 5,093 women).

Overall, the numbers of men and women employed as academics aren’t very different. In 2019, Australian universities employed 54,204 full-time and fractional full-time academics: 28,572 men (53%) and 25,632 (47%) women. It’s the seniority of the positions they hold that differs starkly.

These figures do not include casual staff.

Isn’t the gender balance improving?

Optimists often assure me leadership gender equity is improving. Granted, the percentage of female chancellors in Australian has increased in the past five years. In 2016, WomenCount reported 15% of Australian university chancellors were women. While the increase is positive, it remains disappointing that women occupy only about one-quarter of these increasingly powerful and important roles.

The shift in senior academic ranks has also been slow. In 2009, 73.5% of professors were men. Between 2009 and 2019, the proportion of female professors has risen from 26.5% to 35%. That’s an improvement of less than one percentage point per year on average.

At this rate, it will be the late 2030s before women make up half of the professoriate in Australia.

Read more: Female leaders are missing in academia

Why does gender inequity persist?

The most common reason put forward for gender inequity is related to women’s role in childbearing. But the fact that only women can grow, birth and breastfeed babies does not, on its own, explain why there are 86% more male associate professors and professors than women in these roles, nor why there are nearly three times more male than female vice-chancellors and chancellors. After all, these womanly activities take a relatively short amount of time and most women I know can skilfully multi-task while pregnant and breastfeeding.

However, the fact that women take on the bulk of child-raising duties might help explain the inequities. Of course, people of every gender can equally well raise children. But they don’t – it’s mostly left to the women.

Read more: Flexible work arrangements help women, but only if they are also offered to men

Men are no less capable of picking up children from school but typically it falls to women to do the school run.

Shutterstock

Men are no less capable of picking up children from school but typically it falls to women to do the school run.

Shutterstock

For women, the results of this unequal sharing of responsibility include:

less time and energy for academic pursuits

more teaching (often) and less time for research and publishing

lower academic and leadership profiles (usually)

fewer opportunities to engage in activities that count for promotion and for senior leadership roles.

Of course, not all women have children. And those that do find that they grow up, learn to feed, dress and eventually support themselves and move out of home. Is it also possible that Australian university culture and practices privilege men’s careers and hold back women’s advancement?

University decision-makers, including promotion committees, might well favour men because of:

relatively uninterrupted and neat career trajectories

relatively greater freedom to engage in research and publishing without the disadvantages of part-time employment, never mind the mid-afternoon school run

more easily quantified outputs

more frequent opportunities to lead

the cumulative achievements, profile and trajectory that come with all of the above.

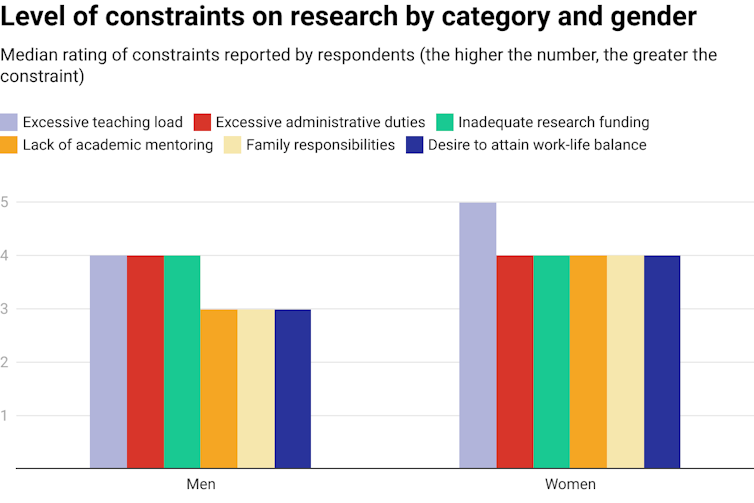

The Conversation. Data: T. Khan & P. Siriwardhane (2020), CC BY

Read more:

How COVID is widening the academic gender divide

Let’s shake up the status quo

Most universities try to redress gender inequity. Committees, agenda items, plans, targets and mentoring programs abound. But evidently these efforts aren’t working.

After many years in executive and governance leadership, I continue to observe decision-makers often thinking of men first, or only of men, when searching for suitable leadership candidates.

On the rarer occasions that women are offered leadership opportunities, they have to adopt the “right” style and carefully balance gravitas and humility. They must learn how to perform gender judo and ensure they don’t fall into the success versus likeability conundrum that Facebook chief operating officer and author Sheryl Sandberg made famous.

In short, to become academic leaders, women must skilfully navigate the unconscious bias and sexism that permeate universities.

While shifts are occurring, they are painfully slow, as the gender data over the past decade and predicted trajectories show. Might it be time for women (and enlightened men) to take matters into their own hands to begin to undermine the status quo? I think so – so I’ve written a book that proposes techniques to adopt to these ends.

What will you do to contribute to greater gender equity?

The Conversation. Data: T. Khan & P. Siriwardhane (2020), CC BY

Read more:

How COVID is widening the academic gender divide

Let’s shake up the status quo

Most universities try to redress gender inequity. Committees, agenda items, plans, targets and mentoring programs abound. But evidently these efforts aren’t working.

After many years in executive and governance leadership, I continue to observe decision-makers often thinking of men first, or only of men, when searching for suitable leadership candidates.

On the rarer occasions that women are offered leadership opportunities, they have to adopt the “right” style and carefully balance gravitas and humility. They must learn how to perform gender judo and ensure they don’t fall into the success versus likeability conundrum that Facebook chief operating officer and author Sheryl Sandberg made famous.

In short, to become academic leaders, women must skilfully navigate the unconscious bias and sexism that permeate universities.

While shifts are occurring, they are painfully slow, as the gender data over the past decade and predicted trajectories show. Might it be time for women (and enlightened men) to take matters into their own hands to begin to undermine the status quo? I think so – so I’ve written a book that proposes techniques to adopt to these ends.

What will you do to contribute to greater gender equity?

Authors: Marcia Devlin, Adjunct Professor, Victoria University