Think big. Why the future of uni campuses lies beyond the CBD

- Written by Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture, University of Adelaide

This is the second of two articles on the past and future of the university campus.

The “dreaming spires” of Oxford University that Matthew Arnold romanticised in 1865 still have a powerful grip on our image of the university. Nevertheless, the university town is part of the past. A key reason for this is the expense of developing facilities on a confined site, particularly in a heritage setting.

Read more: A century that profoundly changed universities and their campuses

The new Beecroft physics building at Oxford is ten storeys high but five are below ground because of government-imposed height restrictions. Unfortunately, this configuration requires a large percentage of floor space to be devoted to stairs, lifts and ventilation ducts. Although the building costs about £5,500 (A$9,840) per square metre of gross floor area, the cost per usable square metre is an eye-watering £15,000. That’s about double the going rate for this type of building on a large-area campus.

The new Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge will cost £300 million for similar reasons.

Expansive campuses dominate overseas

In the 1970s, the University of Heidelberg moved from its site in the town of Heidelberg to a new 112-hectare campus on the north bank of the Neckar River. This enabled the university to develop new space, particularly laboratory space, at economical cost. In the decade after 2007, Heidelberg rose from between 51st and 75th in Science on the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) to 39th. Oxford slipped from tenth to 13th and Cambridge from fourth to seventh.

Of the No. 1 universities in the 54 subjects tracked by the ARWU, including humanities subjects, 84% occupy large campuses of 50 hectares or more.

Aerial view of the University of Paris-Saclay campus under construction in 2015, when it began its first full academic year.

Paris-Saclay

Aerial view of the University of Paris-Saclay campus under construction in 2015, when it began its first full academic year.

Paris-Saclay

The most interesting campus development in the world at the moment is the University of Paris-Saclay. The French government is grabbing the best bits of the University of Paris and assembling them into a super research university. Intended to rank within the ARWU top ten, it is already first in mathematics and 14th overall.

Read more: Why France is building a mega-university at Paris-Saclay to rival Silicon Valley

Paris-Saclay is located on 189ha of farmland south of Paris, close to a railway station. It’s the classic large-area campus. Next to the campus lots of cheap land has been made available for startup companies that will be spun out of the university or existing companies that relocate to use its research or facilities.

ARINA, Author provided

ARINA, Author provided

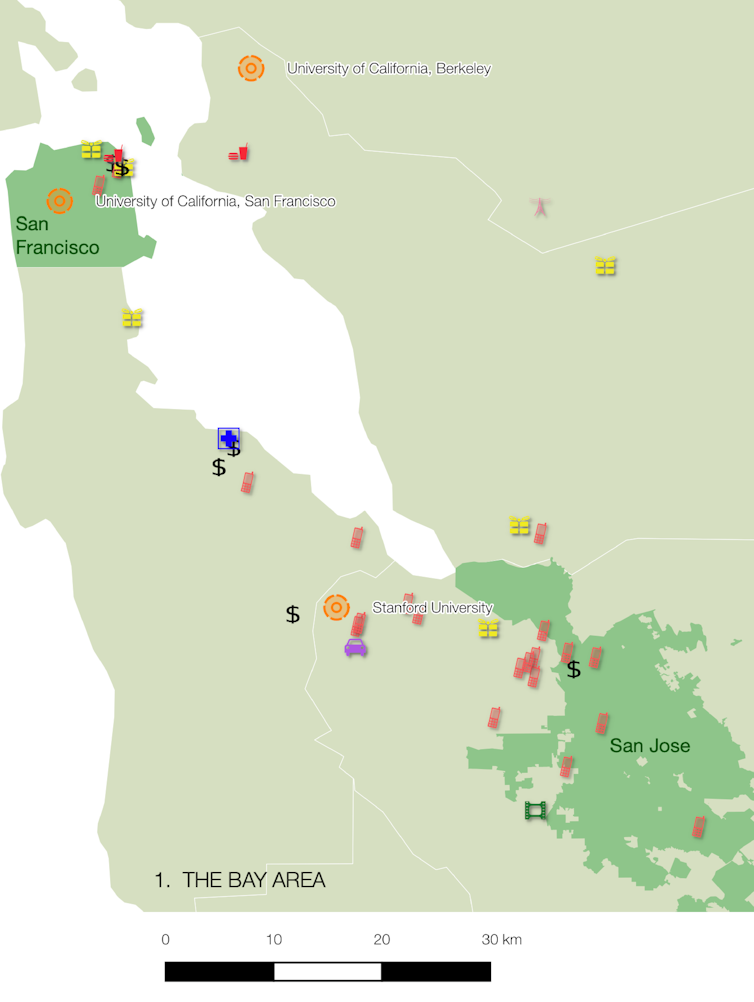

It is another attempt to recreate Silicon Valley, and there’s every reason to try. As part of research by ARINA, an architectural firm specialising in higher education, community and public design, a simple mapping project shows 67% of the market capitalisation of US Fortune 500 Tech companies is located in the triangle between San Francisco, Oakland and San Jose. Two top ten universities, Stanford and UC Berkeley, are also located there.

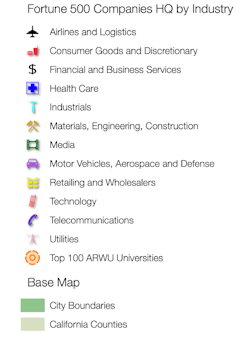

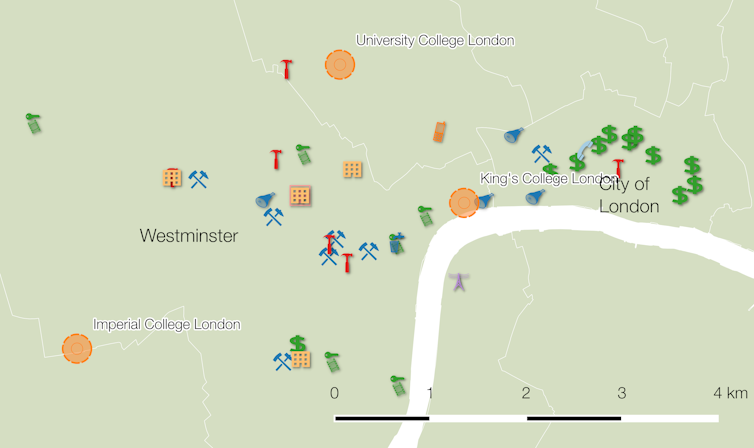

Similarly, in the UK, a belt of high-tech and new-economy industries stretches from Bristol through Oxford, Milton Keynes, Bedford and Cambridge. Also located here are the ARWU top 100 universities of Bristol, Oxford and Cambridge and the nearly-there Warwick.

It is another attempt to recreate Silicon Valley, and there’s every reason to try. As part of research by ARINA, an architectural firm specialising in higher education, community and public design, a simple mapping project shows 67% of the market capitalisation of US Fortune 500 Tech companies is located in the triangle between San Francisco, Oakland and San Jose. Two top ten universities, Stanford and UC Berkeley, are also located there.

Similarly, in the UK, a belt of high-tech and new-economy industries stretches from Bristol through Oxford, Milton Keynes, Bedford and Cambridge. Also located here are the ARWU top 100 universities of Bristol, Oxford and Cambridge and the nearly-there Warwick.

ARINA, Author provided

ARINA, Author provided

More than 50% of the market capitalisation of companies in the FTSE Tech 100 are also located in this area. Only 17% of companies in this index are located in Greater London, and none in central London.

UCL (formerly University College London) is building a new large-area campus at UCL East on the former London Olympics site in Hackney. Its aim is to ease pressure on the 9.7ha UCL campus in Bloomsbury and to provide opportunities for partners to be located close by.

More than 50% of the market capitalisation of companies in the FTSE Tech 100 are also located in this area. Only 17% of companies in this index are located in Greater London, and none in central London.

UCL (formerly University College London) is building a new large-area campus at UCL East on the former London Olympics site in Hackney. Its aim is to ease pressure on the 9.7ha UCL campus in Bloomsbury and to provide opportunities for partners to be located close by.

ARINA, Author provided

What about Australian developments?

In Australia, our most recent efforts at building campuses are a mixed bunch.

The new Western Sydney “Aerotropolis” and the new University of Melbourne campus at Fishermans Bend in Melbourne are plausible because they are expansive campuses with land for partners to invest in nearby facilities. Delivering low and mid-rise buildings on less expensive land served by public transport seems like a good bet.

Macquarie University’s role in the Macquarie Park business and innovation district in Sydney and Deakin’s Waurn Ponds campus in Geelong have successfully attracted private investment and provide evidence that this concept can work.

Other universities have demonstrated how to mess this up. UNSW built a new building to accommodate a commercial partner in photovoltaics. Unfortunately the commercial partner then dropped out. The university was left with a large bill and an empty building.

The key lesson of this, and many other initiatives, is for the university (and government) to deliver attractive intellectual property but to avoid investing in building facilities that the private sector might occupy at some unspecified time in the future. In other words, don’t build and expect them to come.

There are proposals to move the University of Tasmania’s Sandy Bay campus to the Hobart central business district, to create a new CBD campus in Darwin for Charles Darwin University and to shift Edith Cowan University’s Mt Lawley campus into the Perth CBD. As I have argued before, all these proposals are a response to a trend encouraged by the development industry rather than a rational response to issues confronting the higher education sector.

Read more:

A fad, not a solution: 'city deals' are pushing universities into high-rise buildings

Look where world-changing products were born

ARINA research suggests the economy in CBDs is increasingly focused on banking, finance, insurance, property development, accounting and consulting – rentier industries built on income from property or securities that depend on government rather than research to prosper. These are not industries that need a helping hand to grow and they are not industries that initiate change. Putting university campuses physically next to them is pointless.

With its key product, the iPhone (launched in 2008), Apple has probably done more to change the world than any other corporation in recent times. It has done so from a campus in Cupertino, roughly midway between San Jose and Stanford University.

The research that has produced the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine originated in Mainz, Germany, population 217,000. The research for the AstraZeneca vaccine was carried out in the outskirts of Oxford, UK. Moderna’s research facilities are in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near MIT.

Most of the things that have made a difference start in sheds (Boeing and Douglas aircraft companies) or garages (Apple, Google and Hewlett Packard), or cheap office space (Intel).

I start and finish these articles with the observation that it costs about half as much per delivered square metre to build on a large-area campus. Low to mid-rise buildings have more usable space per gross sq m, are more sustainable because they use less embodied energy and are inherently more adaptable.

A very large campus provides space to develop facilities that will be required as research evolves over time. The surrounding land is cheaper and therefore more attractive to the firms that might draw on university research. That’s the “secret” of both Silicon Valley and the UK high-tech belt. And it’s why the University of Paris-Saclay will work.

In Australia, we should contemplate why the Bay Area is so successful, learn from the example of the University of Paris-Saclay and rethink our obsession with CBD campuses.

ARINA, Author provided

What about Australian developments?

In Australia, our most recent efforts at building campuses are a mixed bunch.

The new Western Sydney “Aerotropolis” and the new University of Melbourne campus at Fishermans Bend in Melbourne are plausible because they are expansive campuses with land for partners to invest in nearby facilities. Delivering low and mid-rise buildings on less expensive land served by public transport seems like a good bet.

Macquarie University’s role in the Macquarie Park business and innovation district in Sydney and Deakin’s Waurn Ponds campus in Geelong have successfully attracted private investment and provide evidence that this concept can work.

Other universities have demonstrated how to mess this up. UNSW built a new building to accommodate a commercial partner in photovoltaics. Unfortunately the commercial partner then dropped out. The university was left with a large bill and an empty building.

The key lesson of this, and many other initiatives, is for the university (and government) to deliver attractive intellectual property but to avoid investing in building facilities that the private sector might occupy at some unspecified time in the future. In other words, don’t build and expect them to come.

There are proposals to move the University of Tasmania’s Sandy Bay campus to the Hobart central business district, to create a new CBD campus in Darwin for Charles Darwin University and to shift Edith Cowan University’s Mt Lawley campus into the Perth CBD. As I have argued before, all these proposals are a response to a trend encouraged by the development industry rather than a rational response to issues confronting the higher education sector.

Read more:

A fad, not a solution: 'city deals' are pushing universities into high-rise buildings

Look where world-changing products were born

ARINA research suggests the economy in CBDs is increasingly focused on banking, finance, insurance, property development, accounting and consulting – rentier industries built on income from property or securities that depend on government rather than research to prosper. These are not industries that need a helping hand to grow and they are not industries that initiate change. Putting university campuses physically next to them is pointless.

With its key product, the iPhone (launched in 2008), Apple has probably done more to change the world than any other corporation in recent times. It has done so from a campus in Cupertino, roughly midway between San Jose and Stanford University.

The research that has produced the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine originated in Mainz, Germany, population 217,000. The research for the AstraZeneca vaccine was carried out in the outskirts of Oxford, UK. Moderna’s research facilities are in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near MIT.

Most of the things that have made a difference start in sheds (Boeing and Douglas aircraft companies) or garages (Apple, Google and Hewlett Packard), or cheap office space (Intel).

I start and finish these articles with the observation that it costs about half as much per delivered square metre to build on a large-area campus. Low to mid-rise buildings have more usable space per gross sq m, are more sustainable because they use less embodied energy and are inherently more adaptable.

A very large campus provides space to develop facilities that will be required as research evolves over time. The surrounding land is cheaper and therefore more attractive to the firms that might draw on university research. That’s the “secret” of both Silicon Valley and the UK high-tech belt. And it’s why the University of Paris-Saclay will work.

In Australia, we should contemplate why the Bay Area is so successful, learn from the example of the University of Paris-Saclay and rethink our obsession with CBD campuses.

Authors: Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture, University of Adelaide

Read more https://theconversation.com/think-big-why-the-future-of-uni-campuses-lies-beyond-the-cbd-151766