A century that profoundly changed universities and their campuses

- Written by Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture, University of Adelaide

This history of the development of universities is the first of two articles on the past and future of the campus. This is a long read, so set aside the time to read it and enjoy.

Once the first atomic bomb exploded on July 16 1945 in New Mexico, the world would never be the same again. Scientists and engineers had turned an obscure principle into a weapon of unprecedented power. Los Alamos, the facility where the bomb was designed, was run by the University of California.

This was a turning point for universities. As they increasingly focused on scientific research, the role of universities worldwide – and their campuses – changed.

Before the first world war, the largest investment on most campuses was the university library. After the second world war, investment shifted decisively to laboratories and equipment.

A key reason for the increasing focus on university research was the lessons of the first world war. After the war, governments of rich countries took an increasingly interventionist role in directing and encouraging the research and development of artificial materials, weapons, defences and medicine. Universities or institutes associated with universities did much of this work.

Read more: Universities and government need to rethink their relationship with each other before it's too late

By 1926, the Council for Science and Industrial Research, the predecessor to the CSIRO, and the organisation that would become the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) had been founded in Australia.

A gradual turn towards research

In the UK, many of the older universities were not that keen on applied research. Chemistry, engineering and physics were taught at Oxford between the wars, but by 1939 the chemistry cohort was just over 40 students, of whom “two or three were women”.

It wasn’t until 1937 that Oxford drew up a plan to develop the “Science Area” with new buildings, but in that same year, the university also agreed to reduce its size to avoid a fight with the Town over “further intrusion on the Parks”.

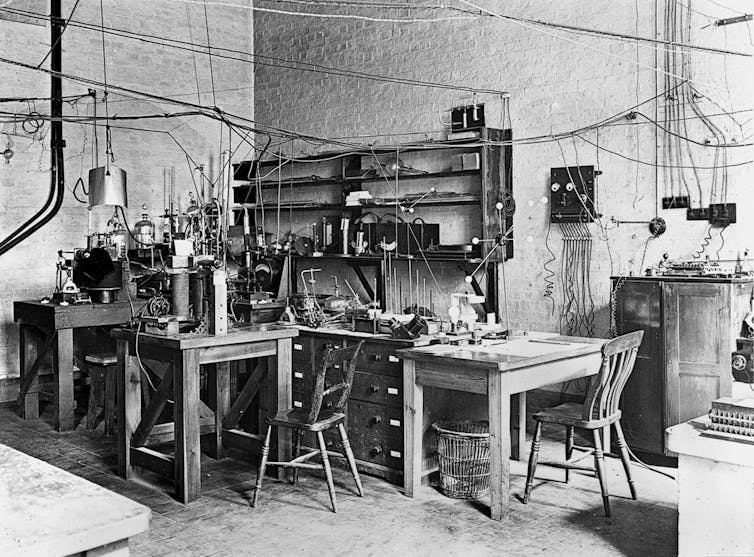

Facilities at Cambridge for physical sciences were slightly better, but not by much, despite its historical focus on mathematics. The Cavendish laboratory in which the New Zealander Ernest Rutherford discovered in 1911 that the atom had a nucleus was small, dark, damp and ill-equipped.

A century ago, universities provided modest facilities for researchers like Nobel laureate Ernest Rutherford.

Science Museum London/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

A century ago, universities provided modest facilities for researchers like Nobel laureate Ernest Rutherford.

Science Museum London/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

This relative lack of interest in experimental sciences at Oxbridge was unhelpful for science research in Australia, because our six small state-run universities tended to follow their lead. As an indication of its priorities, the University of Adelaide built its humanities buildings in stone and its much more modest science facilities in brick.

Nobel laureate and University of Adelaide Professor W.H. Bragg carried out his pioneering experiments on X-ray crystallography in Adelaide during 1900 to 1908 in a converted storeroom in the basement of the Mitchell Building. His lab is now a storeroom again.

The post-war transformations

The application of university research had been a German strength since well before the first world war with the rise of the Humboldtian model of higher education, which favoured research over scholarship. A key reason the Allies prevailed in 1945 was that the United States in particular rapidly improved its capacity to carry out and apply research, based on the Humboldtian model.

In 1917, MIT established a naval aviation school. The University of Washington soon followed MIT’s example.

This decision had a direct bearing on the success of the Boeing company following construction of the Boeing wind tunnel at the University of Washington’s Seattle campus in 1917. It led directly to the development of advanced aerodynamics for the Boeing 247 of 1933, which provided the template for all subsequent commercial airliners.

The Australian university system between the wars offers no such exemplars. The focus on applied research was foreign to the prevailing university culture in Australia at the time. As Hannah Forsyth writes in A History of the Modern Australian University, not until the 1940s did “scholarly esteem began to move away from ‘mastery’ of disciplines towards the discovery of new knowledge”.

The wartime construction of a wind tunnel at the University of Washington enabled development of the Boeing 247, which provided the template for commercial airliners.

Ken Fielding/Flickr, CC BY-SA

The wartime construction of a wind tunnel at the University of Washington enabled development of the Boeing 247, which provided the template for commercial airliners.

Ken Fielding/Flickr, CC BY-SA

New research facilities and new campuses

New technologies led to a host of new post-war industries, including commercial aviation, television, plastics, information technology (IT) and advanced health care. The demand for skills to operate these new industries was the primary driver of an explosion in university enrolments.

University science research in Australia only got a serious start in 1946 with the foundation of the Australian National University (ANU) and the Commonwealth Universities Grants Committee, which became the Australian Research Council (ARC).

The founding of the Australian National University in 1946 marked a shift in Australia towards more research-focused universities set on very large campuses.

EQRoy/Shutterstock

The founding of the Australian National University in 1946 marked a shift in Australia towards more research-focused universities set on very large campuses.

EQRoy/Shutterstock

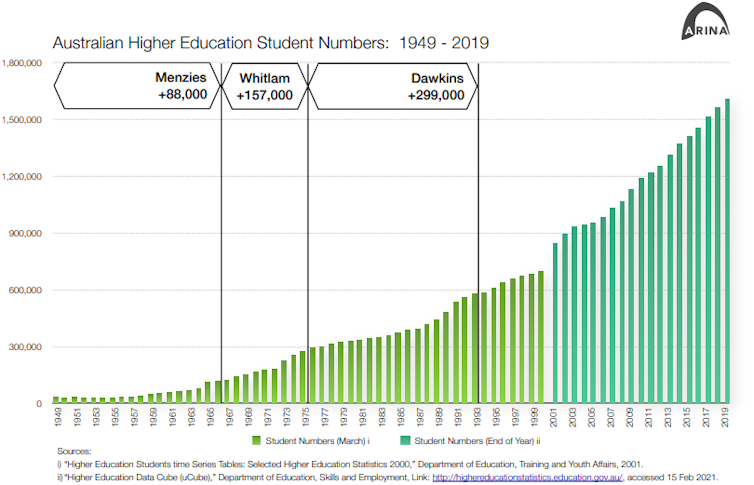

As Robert Menzies, the prime minister from 1949-66, later wrote:

The Second World War brought about great social changes. In the eye of the future observer, the greatest may well provide to be in the field of higher education.

In Australia, about 80% of our universities have been founded since the second world war. The growth of the sector has been startling.

Author provided

Read more:

Australia doesn't have too many universities. Here's why

All of the institutions founded during the Menzies era were sited on large campuses in the suburbs or beyond. Although mainly Commonwealth-funded, they were designed and delivered by state public works authorities to tight budgets on land provided largely by state governments. UNSW, Monash, Griffith, La Trobe, Flinders and WAIT (now Curtin) share a heritage of economical buildings on large parcels of land.

The key reasons for this approach were to minimise cost and maximise capacity for growth and change. Low to medium-rise buildings on land surplus to state needs maximised bang for buck. Development costs per square metre of building were about half that of a campus in the central business district (CBD) of cities.

This was not a new discovery. The universities of Stanford, Berkeley, Caltech, Tokyo, Wisconsin and Peking, all founded in the 19th century, used this model for similar reasons.

Fortunately, the states were generous with land they didn’t need. Of all the universities built in the Menzies era, only UNSW with 39 hectares has a significant land area constraint. The other universities have at least 50ha and several have well over 100ha. This has given them some headaches, but also lots of options.

Research by ARINA, an architectural firm specialising in higher education, community and public design, shows that virtually all universities built since 1949 – that’s more than 90% of universities in the world – have large campuses with densities less than 500 students per hectare. The University of Bath, built in 1966, is typical of post-war UK universities with 59ha and 16,000 students in 2021, less than 300/ha.

The same is true even in small city-states such as Hong Kong and Singapore. The National University of Singapore has a campus of about 140ha with 37,000 students (264/ha) and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology has 55ha with 11,000 students (200/ha).

Author provided

Read more:

Australia doesn't have too many universities. Here's why

All of the institutions founded during the Menzies era were sited on large campuses in the suburbs or beyond. Although mainly Commonwealth-funded, they were designed and delivered by state public works authorities to tight budgets on land provided largely by state governments. UNSW, Monash, Griffith, La Trobe, Flinders and WAIT (now Curtin) share a heritage of economical buildings on large parcels of land.

The key reasons for this approach were to minimise cost and maximise capacity for growth and change. Low to medium-rise buildings on land surplus to state needs maximised bang for buck. Development costs per square metre of building were about half that of a campus in the central business district (CBD) of cities.

This was not a new discovery. The universities of Stanford, Berkeley, Caltech, Tokyo, Wisconsin and Peking, all founded in the 19th century, used this model for similar reasons.

Fortunately, the states were generous with land they didn’t need. Of all the universities built in the Menzies era, only UNSW with 39 hectares has a significant land area constraint. The other universities have at least 50ha and several have well over 100ha. This has given them some headaches, but also lots of options.

Research by ARINA, an architectural firm specialising in higher education, community and public design, shows that virtually all universities built since 1949 – that’s more than 90% of universities in the world – have large campuses with densities less than 500 students per hectare. The University of Bath, built in 1966, is typical of post-war UK universities with 59ha and 16,000 students in 2021, less than 300/ha.

The same is true even in small city-states such as Hong Kong and Singapore. The National University of Singapore has a campus of about 140ha with 37,000 students (264/ha) and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology has 55ha with 11,000 students (200/ha).

The National University of Singapore has a campus of about 150ha despite the city-state’s small area.

EQRoy/Shutterstock

Most new universities in Europe, Asia, India and the Middle East still rely on the large campus model. The University of Paris-Saclay, for example, is being built on 189ha of former farmland 15km south of the Paris orbital motorway.

Broad-acre campuses are popular with students as measured by surveys of educational experience such as the Australasian Survey of Student Engagement (AUSSE) and the US National Survey of

Student Engagement (NESSE). The most popular campuses in Australia are Bond, New England, Griffith and Notre Dame. RMIT and UTS, the highest-ranked CBD campuses finish in the middle of the pack, a long way behind the leaders. A similar phenomenon can be seen in the UK and the US.

Read more:

Looking beyond the sandstone: universities reinvent campuses to bring together town and gown

Campus model goes corporate

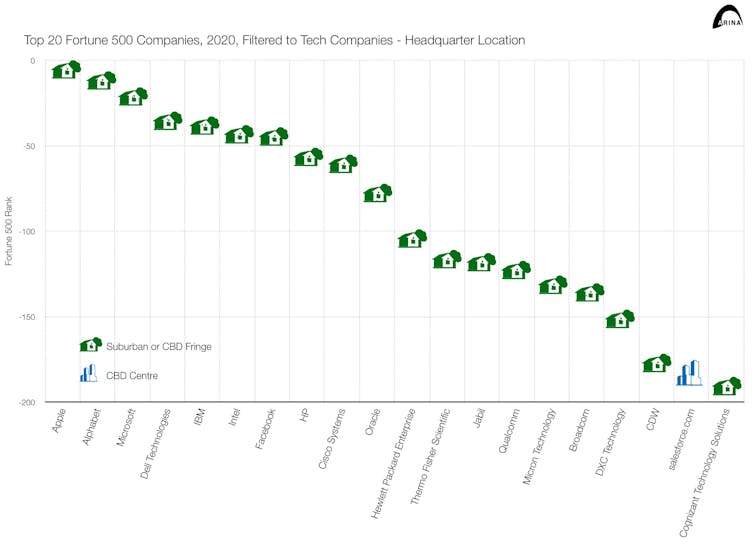

The ARINA research indicates broad-acre campus models have also become increasingly part of the physical organisation and accommodation of many commercial operations.

In 2020, 63% of the top 30 US Fortune 500 index and 87% of the top 30 tech companies in the index were located in suburban and extra-urban settings, mostly campuses. This includes well-known tech companies such as Apple, Alphabet, Facebook, Tesla and HP, but also less obvious candidates such as Walmart, Exxon Mobil and Amazon.

The National University of Singapore has a campus of about 150ha despite the city-state’s small area.

EQRoy/Shutterstock

Most new universities in Europe, Asia, India and the Middle East still rely on the large campus model. The University of Paris-Saclay, for example, is being built on 189ha of former farmland 15km south of the Paris orbital motorway.

Broad-acre campuses are popular with students as measured by surveys of educational experience such as the Australasian Survey of Student Engagement (AUSSE) and the US National Survey of

Student Engagement (NESSE). The most popular campuses in Australia are Bond, New England, Griffith and Notre Dame. RMIT and UTS, the highest-ranked CBD campuses finish in the middle of the pack, a long way behind the leaders. A similar phenomenon can be seen in the UK and the US.

Read more:

Looking beyond the sandstone: universities reinvent campuses to bring together town and gown

Campus model goes corporate

The ARINA research indicates broad-acre campus models have also become increasingly part of the physical organisation and accommodation of many commercial operations.

In 2020, 63% of the top 30 US Fortune 500 index and 87% of the top 30 tech companies in the index were located in suburban and extra-urban settings, mostly campuses. This includes well-known tech companies such as Apple, Alphabet, Facebook, Tesla and HP, but also less obvious candidates such as Walmart, Exxon Mobil and Amazon.

ARINA, Author provided

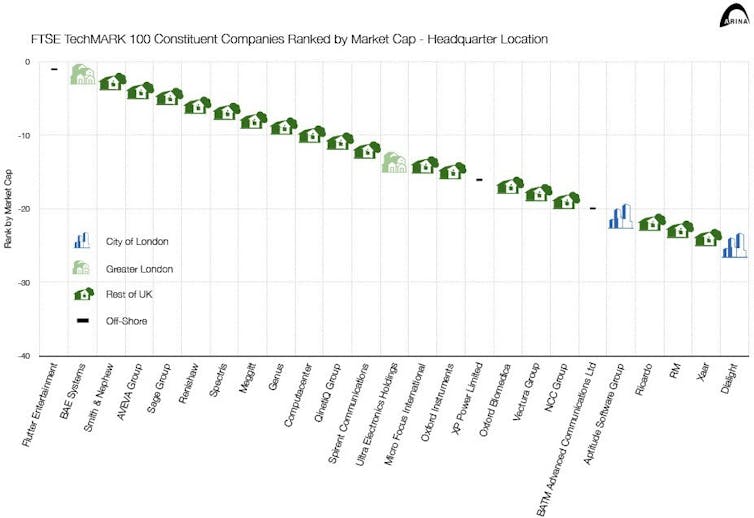

In the UK, 28% of all FTSE 100 companies and 54% of FTSE Techmark 100 companies by market capitalisation are based outside greater London.

ARINA, Author provided

In the UK, 28% of all FTSE 100 companies and 54% of FTSE Techmark 100 companies by market capitalisation are based outside greater London.

ARINA, Author provided

The reasons for this are straightforward: capital and operating costs for research-based firms are lower outside a CBD. While some Australian universities are choosing to head into the city, much of the new economy appears to be heading for the suburbs. It’s happening for the same reason that universities started to migrate there over a hundred years ago.

Read more:

The rise of the corporate campus

ARINA, Author provided

The reasons for this are straightforward: capital and operating costs for research-based firms are lower outside a CBD. While some Australian universities are choosing to head into the city, much of the new economy appears to be heading for the suburbs. It’s happening for the same reason that universities started to migrate there over a hundred years ago.

Read more:

The rise of the corporate campus

Authors: Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture, University of Adelaide

Read more https://theconversation.com/a-century-that-profoundly-changed-universities-and-their-campuses-151765