First lift JobSeeker, then add on fully-funded unemployment insurance

- Written by Steven Hamilton, Visiting Fellow, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

A chorus of voices is calling for the government to “raise the rate” of the JobSeeker unemployment benefit, among them the Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe. And they’re right.

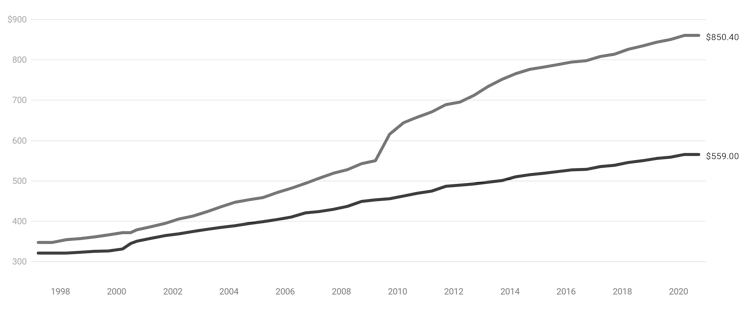

Once about as much as the age pension (and until recently called Newstart), JobSeeker is now less than two-thirds of it.

When the temporary coronavirus supplement ends on April 1, JobSeeker’s inability to provide a decent standard of living while unemployed will become mercilessly apparent.

JobSeeker versus the age pension

Dollars per fortnight, base rate, single.

Source: Ben Phillips ANU, DSS

Dollars per fortnight, base rate, single.

Source: Ben Phillips ANU, DSS

After JobSeeker is boosted, something the government is considering, there’s something else we should fix.

Right now JobSeeker is being asked to simultaneously serve two very different groups: those transitioning out of and back into work for a brief period (say, less than a year) and those in longer-term unemployment.

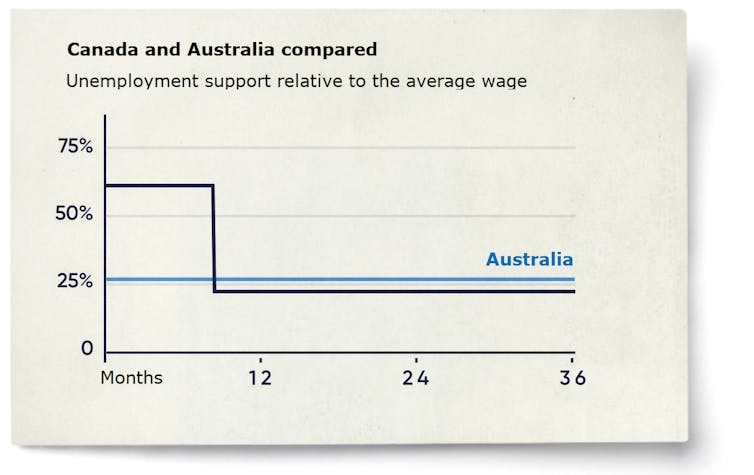

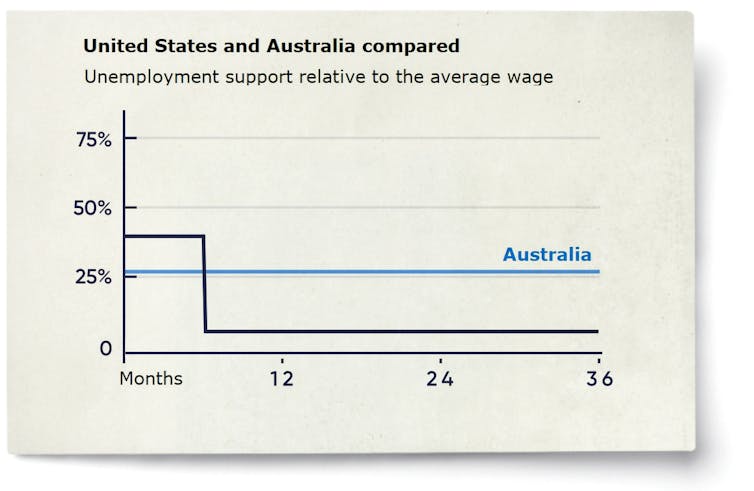

On this, Australia is an outlier.

Every member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development other than Britain, Ireland, and New Zealand offers a high, fairly generous, and time-limited initial payment (usually a portion of the former wage) that steps down at a later date.

In Canada the initial payment is 62% of average wages, falling to 23% after nine months. In the United States it is 40%, falling back to very little after six months.

Every member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development other than Britain, Ireland, and New Zealand offers a high, fairly generous, and time-limited initial payment (usually a portion of the former wage) that steps down at a later date.

In Canada the initial payment is 62% of average wages, falling to 23% after nine months. In the United States it is 40%, falling back to very little after six months.

The high initial rate helps people weather the temporary income shock of unemployment, and provides breathing space to search for a job that’s right.

Because our system doesn’t distinguish between the short- and long-term unemployed, Australians experiencing short-term unemployment receive the least-generous payment in the developed world.

Our rate of long-term support is actually middle of the road by OECD standards, despite being well below the poverty line.

Proper insurance

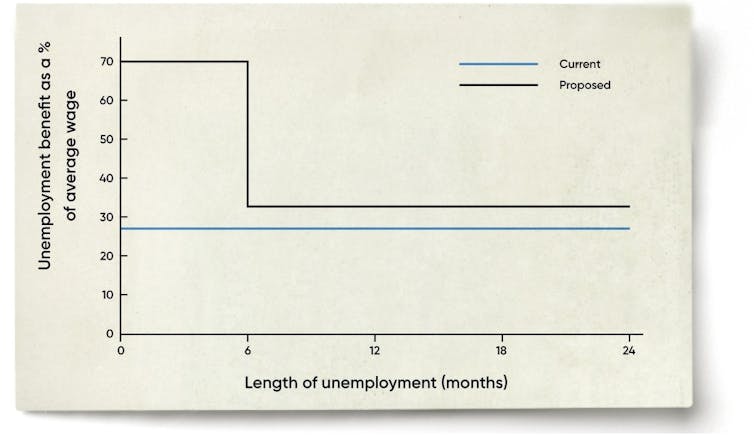

In a policy proposal released this week by the Blueprint Institute, we suggest something better, an unemployment insurance system I have called JobMatcher.

JobMatcher would pay newly unemployed people 70% of their previous wage for six months, providing what US researchers believe is enough time to find the right job.

After six months, they would be supported by the JobSeeker payment.

JobMatcher would have a number of economic benefits:

Getting people off the dole faster. Frontloading benefits has been found to speed up reemployment by providing a hard deadline after which support will be reduced.

Getting workers back into better jobs. Step-down systems of unemployment insurance provide more generous support workers at the start of unemployment, enabling them to find jobs better suited to their skills. These jobs are more likely to be full-time, last longer, and pay higher wages.

Smoothing the temporary income shock of losing work. JobMatcher would cushion the initial income shock of short-term unemployment far better than JobSeeker is likely to, providing recipients with time and space to adjust their adjust their lifestyle and debt obligations.

Serving as an automatic stabiliser. Unemployment insurance stabilises consumer spending by smoothing fluctuations in disposable incomes.

Other evidence suggests that a step-down scheme such as JobMatcher would boost wages, productivity, innovation, and worker retention.

First things first

First, JobSeeker needs to be increased. A reasonable boost would be $150 per fortnight, to replace the coronavirus supplement which is about to end.

And it should be indexed to wages rather than prices to keep pace with living standards.

With JobMatcher, payments to the unemployed would look like this:

The high initial rate helps people weather the temporary income shock of unemployment, and provides breathing space to search for a job that’s right.

Because our system doesn’t distinguish between the short- and long-term unemployed, Australians experiencing short-term unemployment receive the least-generous payment in the developed world.

Our rate of long-term support is actually middle of the road by OECD standards, despite being well below the poverty line.

Proper insurance

In a policy proposal released this week by the Blueprint Institute, we suggest something better, an unemployment insurance system I have called JobMatcher.

JobMatcher would pay newly unemployed people 70% of their previous wage for six months, providing what US researchers believe is enough time to find the right job.

After six months, they would be supported by the JobSeeker payment.

JobMatcher would have a number of economic benefits:

Getting people off the dole faster. Frontloading benefits has been found to speed up reemployment by providing a hard deadline after which support will be reduced.

Getting workers back into better jobs. Step-down systems of unemployment insurance provide more generous support workers at the start of unemployment, enabling them to find jobs better suited to their skills. These jobs are more likely to be full-time, last longer, and pay higher wages.

Smoothing the temporary income shock of losing work. JobMatcher would cushion the initial income shock of short-term unemployment far better than JobSeeker is likely to, providing recipients with time and space to adjust their adjust their lifestyle and debt obligations.

Serving as an automatic stabiliser. Unemployment insurance stabilises consumer spending by smoothing fluctuations in disposable incomes.

Other evidence suggests that a step-down scheme such as JobMatcher would boost wages, productivity, innovation, and worker retention.

First things first

First, JobSeeker needs to be increased. A reasonable boost would be $150 per fortnight, to replace the coronavirus supplement which is about to end.

And it should be indexed to wages rather than prices to keep pace with living standards.

With JobMatcher, payments to the unemployed would look like this:

Proper premiums

JobMatcher would be paid for with proper insurance premiums.

The government would charge most workers an annual JobMatcher premium equal to 1% of income, along the lines of the 2% Medicare levy.

Paying in to the system would do more than merely fund it. It would engender in people who have lost their jobs the belief that they had the right to use it.

And it would engender broader public support for the high payments involved.

Proper premiums

JobMatcher would be paid for with proper insurance premiums.

The government would charge most workers an annual JobMatcher premium equal to 1% of income, along the lines of the 2% Medicare levy.

Paying in to the system would do more than merely fund it. It would engender in people who have lost their jobs the belief that they had the right to use it.

And it would engender broader public support for the high payments involved.

Authors: Steven Hamilton, Visiting Fellow, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University