Global weekly COVID cases are falling, WHO says — but 'if we stop fighting it on any front, it will come roaring back'

- Written by Adam Kamradt-Scott, Associate professor, University of Sydney

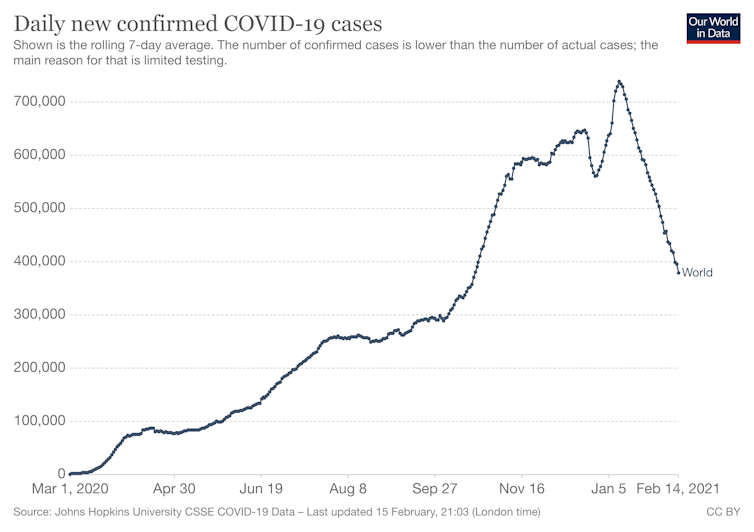

The number of reported global weekly COVID cases is falling and has dropped nearly 50% this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) said overnight. This incredibly encouraging news shows the power of public health measures — but we must remain vigilant. Letting our guard down now, when new variants are emerging, could easily reverse the trend.

According to a WHO press release:

“Last week saw the lowest number of reported weekly cases since October”, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) told journalists at a regular press briefing in Geneva.

Noting a nearly 50% drop this year, he stressed that “how we respond to this trend” is what matters now.

While acknowledging that there is more reason for hope of bringing the pandemic under control, the WHO chief warned, “the fire is not out, but we have reduced its size”.

“If we stop fighting it on any front, it will come roaring back”.

Director-General of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said ‘If we stop fighting it on any front, it will come roaring back’.

Jean-Christophe Bott/AP/AAP

Director-General of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said ‘If we stop fighting it on any front, it will come roaring back’.

Jean-Christophe Bott/AP/AAP

Read more: Are vaccines already helping contain COVID? Early signs say yes, but mutations will be challenging

This welcome news shows that when governments respond rapidly by putting in place public health measures, we reap the benefits even before widespread vaccine rollouts. That’s a really important message now, and for when the next pandemic hits (and another one eventually will).

As good as this news is, though, we are still seeing infections in fairly large numbers worldwide. And, as we have regrettably seen in the past, subsequent waves of infection can easily emerge.

We also now have a series of variants to contend with. Even as begin to understand how the variants now circulating will affect the effectiveness of current vaccines, it’s possible we could see yet another new variant emerge that would reverse the downward trend. This remains a real risk when there are still so many new infections worldwide and when so few countries have been able to start vaccinating.

Our World in Data

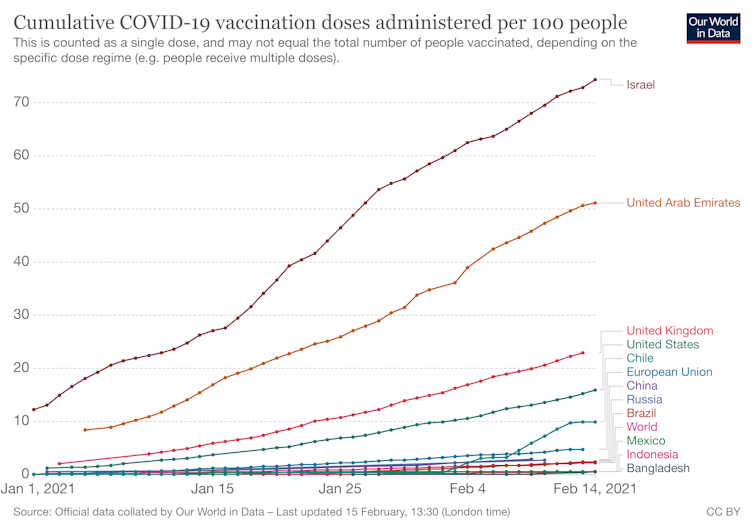

It’s too early to see vaccine effect

Some countries, such as Israel and the United Kingdom, have already vaccinated huge swathes of their population. That’s a tremendous achievement and we will start to see the benefits in the coming months. But fundamentally, it’s too early to see the effect of the vaccine rollout in widespread reduction of infection.

Our World in Data

It’s too early to see vaccine effect

Some countries, such as Israel and the United Kingdom, have already vaccinated huge swathes of their population. That’s a tremendous achievement and we will start to see the benefits in the coming months. But fundamentally, it’s too early to see the effect of the vaccine rollout in widespread reduction of infection.

Our World in Data

On the other hand, we have recently seen a much greater focus on public health measures in places such as Europe, the Middle East and the United States. These places have been significantly affected by COVID outbreaks and are dealing with third waves, as some are preparing for their fourth.

It’s likely these public health measures — such as lockdowns, physical distancing, mask-wearing and increased hygiene measures — are what’s driving the global downward trend. That shows the benefit when leaders do engage and bring their populations with them.

To keep that trend going in the right direction, we need high levels of public compliance with those public health measures and more equitable access to vaccines globally.

Unequal global access to vaccines is a major risk

Very few low-income countries have started a widespread vaccine rollout, and many are struggling to secure doses. Having unequal access globally to vaccines is obviously morally wrong and dangerous — but it also represents a great economic risk to high income countries like Australia.

Having high-income countries buying up all the stock of vaccines and leaving poorer nations with little recourse will prolong the pandemic. And that’s bad news for the global economy, with estimates suggesting the pandemic will cost US$16 trillion dollars.

Our World in Data

On the other hand, we have recently seen a much greater focus on public health measures in places such as Europe, the Middle East and the United States. These places have been significantly affected by COVID outbreaks and are dealing with third waves, as some are preparing for their fourth.

It’s likely these public health measures — such as lockdowns, physical distancing, mask-wearing and increased hygiene measures — are what’s driving the global downward trend. That shows the benefit when leaders do engage and bring their populations with them.

To keep that trend going in the right direction, we need high levels of public compliance with those public health measures and more equitable access to vaccines globally.

Unequal global access to vaccines is a major risk

Very few low-income countries have started a widespread vaccine rollout, and many are struggling to secure doses. Having unequal access globally to vaccines is obviously morally wrong and dangerous — but it also represents a great economic risk to high income countries like Australia.

Having high-income countries buying up all the stock of vaccines and leaving poorer nations with little recourse will prolong the pandemic. And that’s bad news for the global economy, with estimates suggesting the pandemic will cost US$16 trillion dollars.

Some countries, such as the UK and Israel, have begun mass COVID vaccination programs. But it’s probably too early to see widespread impact.

Joe Giddens/POOL/EPA/AAP

Even if Australia were able to maintain its success so far, having the pandemic run out of control in other countries means no travel, will continue to make it hard for Australians to return home, and could lead to shortages of products and materials from other countries. As the global financial crisis showed, economic strife in other parts of the world can have profound impact locally, even when Australia is doing relatively OK.

The risk this poses to lives and to the global economy is one reason the WHO has called for vaccine rollouts to begin in all countries in the first 100 days of 2021, and for health-care workers in lower- and middle-income countries to be protected first.

The WHO has issued a vaccine equity declaration calling for, among other things, world leaders to increase contributions to the UN-led vaccine equity initiative, COVAX, and to share doses with COVAX even as they roll out their own national campaigns.

We also clearly need to upscale vaccine research and manufacturing capacity around the world, which would also help us respond to the next pandemic, too.

There’s still a lot of work to be done.

Relaxing too soon can undo our progress

As the WHO’s Director-General said overnight, the fire is not out and “if we stop fighting it on any front, it will come roaring back”.

That’s why sticking to the fundamentals of infection control is so important. That means keeping up with the hand-washing and physical distancing. It means wearing a mask if you can’t physically distance and complying with lockdowns and other public health orders. Yes, it’s hard to maintain a high level of commitment, but the alternative is far worse.

When people start to hear that global case numbers are improving, there’s a tendency to relax — and that’s risky. Now is the time we need to work together to see this contained, and ideally suppressed.

We may never completely eradicate this virus. But if we stick with the public health measures, and vaccinate as many people as possible worldwide, we can keep the trend going in the right direction.

Read more:

UK, South African, Brazilian: a virologist explains each COVID variant and what they mean for the pandemic

Some countries, such as the UK and Israel, have begun mass COVID vaccination programs. But it’s probably too early to see widespread impact.

Joe Giddens/POOL/EPA/AAP

Even if Australia were able to maintain its success so far, having the pandemic run out of control in other countries means no travel, will continue to make it hard for Australians to return home, and could lead to shortages of products and materials from other countries. As the global financial crisis showed, economic strife in other parts of the world can have profound impact locally, even when Australia is doing relatively OK.

The risk this poses to lives and to the global economy is one reason the WHO has called for vaccine rollouts to begin in all countries in the first 100 days of 2021, and for health-care workers in lower- and middle-income countries to be protected first.

The WHO has issued a vaccine equity declaration calling for, among other things, world leaders to increase contributions to the UN-led vaccine equity initiative, COVAX, and to share doses with COVAX even as they roll out their own national campaigns.

We also clearly need to upscale vaccine research and manufacturing capacity around the world, which would also help us respond to the next pandemic, too.

There’s still a lot of work to be done.

Relaxing too soon can undo our progress

As the WHO’s Director-General said overnight, the fire is not out and “if we stop fighting it on any front, it will come roaring back”.

That’s why sticking to the fundamentals of infection control is so important. That means keeping up with the hand-washing and physical distancing. It means wearing a mask if you can’t physically distance and complying with lockdowns and other public health orders. Yes, it’s hard to maintain a high level of commitment, but the alternative is far worse.

When people start to hear that global case numbers are improving, there’s a tendency to relax — and that’s risky. Now is the time we need to work together to see this contained, and ideally suppressed.

We may never completely eradicate this virus. But if we stick with the public health measures, and vaccinate as many people as possible worldwide, we can keep the trend going in the right direction.

Read more:

UK, South African, Brazilian: a virologist explains each COVID variant and what they mean for the pandemic

Authors: Adam Kamradt-Scott, Associate professor, University of Sydney