Despite being permanently banned, Trump's prolific Twitter record lives on

- Written by Audrey Courty, PhD candidate, School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science, Griffith University

For years, US President Donald Trump pushed the limits of Twitter’s content policies, raising pressure on the platform to exercise tougher moderation.

Ultimately, the violent siege of the US Capitol forced Twitter’s hand and the platform permanently banned Trump’s personal account, @realDonaldTrump.

But this doesn’t mean the 26,000 or so tweets posted during his presidency have vanished. They are now a matter of public record — and have been preserved accordingly.

Read more: Twitter permanently suspends Trump after U.S. Capitol siege, citing risk of further violence

The de-platforming of Donald Trump

The loss of public access to Trump’s original Twitter posts means every online hyperlink to a tweet is now defunct. Embedded tweets are still visible as simple text, but can no longer be traced to their source.

Adding to this, retweets of the president’s messages no longer appear on the forwarding user’s feed. Quote tweets have been replaced with the message: “This Tweet is unavailable” and replies can’t be viewed in one place anymore.

But even if Trump’s account had not been suspended, he would have had to part with it at the end of his presidency anyway, since he used it extensively for presidential purposes.

Under the US government’s ethics regulations, US officials are prevented from benefiting personally from their public office, and this applies to social media accounts.

Former US ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, also used her personal and political Twitter accounts to conduct official business as ambassador. The account was wiped and renamed in 2019 once her role ended.

Where did all the information go?

Despite being permanently suspended, Trump’s prolific Twitter record is not lost. Under the Presidential Records Act, all of Trump’s social media communications are considered public property, including non-public messages sent via direct chat features.

The act defines presidential records as any materials created or received by the president (or immediate staff or advisors) in the course of conducting his official duties.

It was passed in 1978, out of concern that former president Richard Nixon would destroy the tapes which ultimately led to his resignation. Today, it remains a way to force governments to be transparent with the public.

And although Trump tweeted extensively from his personal Twitter account created in 2009, @realDonaldTrump, it has undoubtedly been used for official purposes.

From banning transgender military service to threatening the use of nuclear weapons against North Korea, his tweets on this account constitute an important part of the presidential record.

As such, the US National Archives says it will preserve all of them, including deleted posts — as well as all posts from @POTUS, the official presidential account.

The Trump administration will have to turn over the digital records for both accounts on January 20, which will eventually be made available to the public on a Trump Library website.

Still, the president reserves the right to invoke as many as six specific restrictions to public access for up to 12 years.

We don’t know whether Trump will invoke restrictions. But even if he does, grassroots initiatives have already archived all of his tweets.

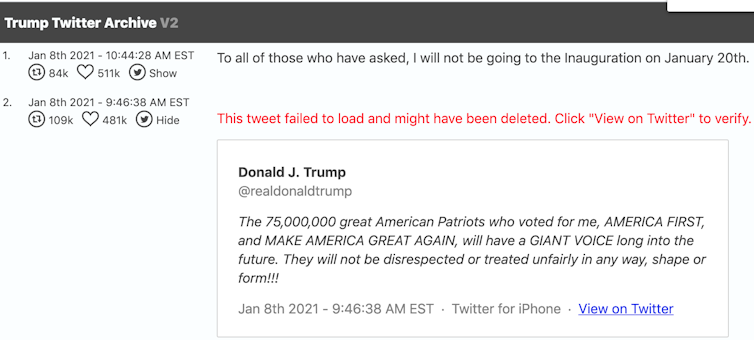

For example, the Trump Twitter Archive is a free, public resource that lets users search and filter through more than 56,000 tweets by Trump since 2009, including deleted tweets since 2016.

The Trump Twitter Archive, started in 2016, is currently one of few extensive online databases providing access to the president’s past tweets.

Screenshot

The Trump Twitter Archive, started in 2016, is currently one of few extensive online databases providing access to the president’s past tweets.

Screenshot

A matter of public record

In 2017, Trump told Fox News he believed he may have never been elected without Twitter — and that he viewed it as an effective means for pushing his message.

Twitter also benefited from this relationship. Trump’s 88 million followers (as of when his account was suspended) generated endless streams of user engagement for the social media giant.

Trump’s approach to using Twitter was unprecedented. He bypassed traditional media channels, instead tweeting for political and diplomatic purposes — including to make important policy announcements.

His tweets set the agenda for US politics during his presidency. For example, they influenced foreign relations between the US and Mexico, North Korea, China and Iran. They were also used to endorse allies and attack rivals.

Read more: Twitter diplomacy: how Trump is using social media to spur a crisis with Mexico

The closest thing to a town square

For all the reasons listed above, the value of Trump’s Twitter record extends beyond historical research. It’s a way to hold him accountable for what he has said and done.

And this will soon be on display as the US Democratic Party looks to impeach him for the second time for “inciting insurrection”.

Trump’s administration of “alternative facts” has continuously stonewalled a number of enquiries — going as far as refusing to testify before Congress on certain matters.

From this frame of view, Trump’s Twitter feed was arguably one of few places where his claims and decisions could really be scrutinised. And indeed, news coverage of the president often relied heavily on this.

The US Capitol building in Washington was stormed by thousands of pro-Trump rioters on Wednesday. Trump in response tweeted a video in which he called the agitators ‘very special’ and said he loved them.

AP

The US Capitol building in Washington was stormed by thousands of pro-Trump rioters on Wednesday. Trump in response tweeted a video in which he called the agitators ‘very special’ and said he loved them.

AP

The amplification effect

The media’s reliance on president Trump’s tweets ultimately highlights a key aspect that governs today’s hybrid media system. That is, it’s highly responsive to a populist communication style.

Trump’s use of Twitter indirectly contributed to his election success in 2016, by helping boost media coverage of his campaign. Researchers also observed him strategically increasing his Twitter activity in line with waning news interest.

Through a constant stream of provocative remarks, Trump exploited news values and continuously inserted himself into the news cycle. And for journalists under pressure to churn out content, his impassioned messages were the perfect sound bites.

Now, stripped of his favourite mouthpiece, it’s uncertain whether Trump will find another way to exert his influence. But one thing is for sure: his time on Twitter will go down in history.

Authors: Audrey Courty, PhD candidate, School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science, Griffith University