3 reasons meeting climate targets and dumping Kyoto credits won't salvage Australia’s international reputation

- Written by Matt McDonald, Associate Professor of International Relations, The University of Queensland

Today, the Morrison government released updated projections of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, which indicate Australia is on track to meet 2030 Paris targets without using “carryover” credits earned from the Kyoto Protocol period.

Australia’s plan to use Kyoto carryover credits to meet Paris targets have long been contentious. The government claims that because emissions fell by more than Australia had committed to under the Kyoto Protocol, they should be allowed to carry these “credits” forward to the Paris agreement. Yet legal experts and other governments have suggested there’s no basis for applying these to the Paris agreement, which is a separate agreement.

The new modelling is good news for the Morrison government, which has been under increasing domestic and international pressure over its climate policy. And Prime Minister Scott Morrison is likely to announce this development proudly at the virtual Pacific Islands Forum on Friday night.

So are the latest projections enough to salvage Australia’s reputation on this issue? That appears unlikely.

Dumping credits

Under the Paris Agreement, Australia committed to reducing emissions by 26-28% of 2005 levels by 2030. This target has been widely criticised for years for being too meagre, but previous modelling had suggested even meeting this target was unlikely unless carryover credits were used.

Read more: Emissions projections indicate Australia won't need carryover credits to meet Paris targets

The latest modelling suggests if the recently-announced technology roadmap — a policy which will support new and emerging clean energy technologies — is taken into account, then Australia would beat its 2030 target by 145 million tonnes. In other words, by 2030 Australia could be 29% under 2005 levels, without using carryover credits.

Morrison had flagged he would announce that Australia will dump the Kyoto credits at a global leaders’ climate summit at the weekend. However, it’s unlikely he’ll be given a speaking slot by the hosts, a reflection of his failure to make meaningful climate commitments. This is why he’ll probably make the announcement to Pacific leaders tomorrow night instead.

Pacific Island leaders were unimpressed with Australia’s climate commitments after last year’s Pacific Islands Forum.

AAP Image/Mick Tsikas

Pacific Island leaders were unimpressed with Australia’s climate commitments after last year’s Pacific Islands Forum.

AAP Image/Mick Tsikas

But even if Morrison announces he’ll scrap the controversial carryovers tomorrow, our international counterparts will still regard Australia as a climate change laggard. There are three big reasons why.

1. Our Paris target is still unambitious

A reduction of 26-28% by 2030 from 2005 levels is well below the commitments of other countries under the Paris Agreement. And under the Paris Agreement, states were encouraged to ratchet up their commitments to emissions over time.

Yet unlike other countries, Australia has not made any indication of a plan to outline a more ambitious contribution ahead of the CoP26 meeting in Glasgow next year.

It’s also worth recalling Australia’s 2005 baseline is a comparatively easy starting point. Under the Kyoto Protocol, Australia was one of only two developed countries allowed to increase its greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2008-12.

This means most other developed countries had already reduced emissions in sectors where it was easiest for them to do so — the “low hanging fruit”. This makes further commitments under Paris more challenging for those countries than Australia.

2. Improved projections are no thanks to federal policy

If we don’t have to use Kyoto carry-over credits to meet Paris targets, it may be despite — rather than because — of federal government policy.

Simply put, much of the decline in (projected) emissions can be attributed to the actions of state governments, which have more actively supported the renewable energy sector.

The revision in the 2020 projections partly reflects new measures to speed up development and deployment of low emissions technologies in the recent budget.

Shutterstock

The revision in the 2020 projections partly reflects new measures to speed up development and deployment of low emissions technologies in the recent budget.

Shutterstock

By contrast (and despite claims to the contrary) the government continues to commit billions of dollars to subsidising the fossil fuel industry. Yet there are clear indications of a declining future market for coal in particular.

Read more: Matt Canavan says Australia doesn't subsidise the fossil fuel industry, an expert says it does

While the technology investment roadmap, a federal policy, may serve to further drive down emissions, this is still far from clear.

3. There’s still no commitment to a net zero emissions timetable

The European Union has had a long-standing commitment to net zero emissions by 2050. More recently it has been joined by other major emitters in Japan and South Korea, while emissions giant China has committed to net zero emissions by 2060.

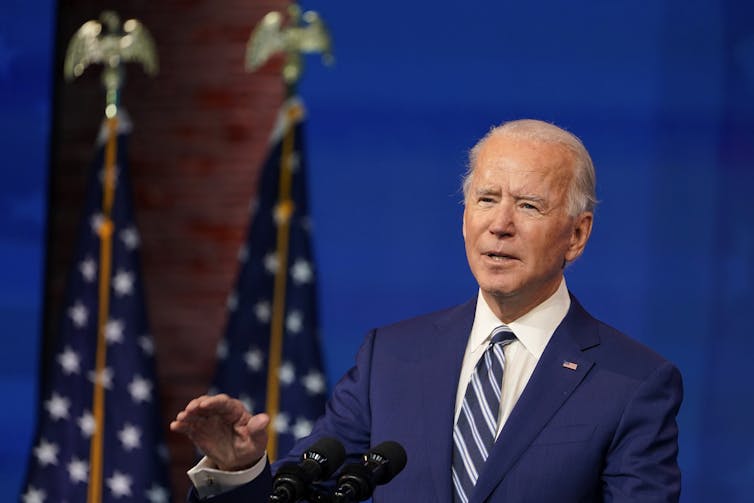

US President-elect Joe Biden has also committed the US to reach net zero emissions by 2050, and to return the US to the Paris agreement.

Under a Biden administration, the US will have the most progressive position on climate change in the nation’s history.

AP Photo/Susan Walsh

Under a Biden administration, the US will have the most progressive position on climate change in the nation’s history.

AP Photo/Susan Walsh

And yet, the Morrison government continues to baulk at setting a net zero emissions timetable, preferring to describe this as a general ambition rather than endorse a specific target or date.

The response from the Pacific will be telling

Australia consistently ranks among the worst performers internationally on the Climate Change Performance Index, and there are indications already that other states will actively pressure Australia on climate ambition and action in the lead up to the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26).

Combined with steadily growing domestic pressure to act on climate change and weakening financial prospects for Australia’s coal exports, international pressure may contribute to a perfect storm for the Morrison government on climate policy.

The response Morrison receives at the virtual Pacific Islands Forum to this position will be telling.

Read more: Pacific Island nations will no longer stand for Australia's inaction on climate change

The region has long been deeply critical of Australia’s climate policy, and is at the frontlines of climate change impacts such as sea level rises, natural disasters and ocean acidification.

While Morrison may avoid the same diplomatic fallout from the 2019 Pacific Islands Forum on this issue, he’s unlikely to find an audience wholly convinced Australia now recognises the scale of the threat climate change poses.

Authors: Matt McDonald, Associate Professor of International Relations, The University of Queensland