Streeton: an optimistic celebration of the golden boy of Australian art

- Written by Joanna Mendelssohn, Principal Fellow (Hon), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, University of Melbourne

Review: Streeton, Art Gallery of New South Wales.

The Art Gallery of New South Wales has launched its summer season with a large, optimistic reconsideration of one of Australian art’s most favoured sons.

Curator Wayne Tunnicliffe has indicated that his decision to name the exhibition simply Streeton, without any subtitles, was part of his strategy to emphasise Streeton’s importance to Australian art and culture.

This assessment is hardly new. Lionel Lindsay, in The Art of Arthur Streeton of 1919 called him “our national painter”.

In 1923 when Streeton’s The Purple Noon’s Transparent Might was first exhibited in London, Lindsay wrote,

Streeton has painted the light and colour of Australia with such truth and beauty that his service to our country must ever remain the equivalent of Constable’s to England.

Arthur Streeton, The Purple Noon’s Transparent Might 1896 oil on canvas, 123 x 123 cm National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne,

purchased 1896.

Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Arthur Streeton, The Purple Noon’s Transparent Might 1896 oil on canvas, 123 x 123 cm National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne,

purchased 1896.

Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Six years later, in 1929, James S. MacDonald, the then director of the AGNSW, claimed Streeton

has shown us our land as no one else has done, and is still our best exemplar of the craft and mystery of painting as applied to landscape.

Nora Streeton, Arthur Streeton with palette in Venice 1908.

Private collection

Nora Streeton, Arthur Streeton with palette in Venice 1908.

Private collection

In 1931, as a way of lifting spirits in the Great Depression, the cash-strapped gallery gave Streeton the first ever survey exhibition of work by a living Australian artist.

In the years between the two world wars, Streeton’s characteristic paintings of blue tinged bush, golden fields, and clear Australian skies spoke of a country that had never seen war. His work was easily seen as characteristic of Australian smug insularity.

Most are pure landscapes but some show stocky soldier settlers attempting to tame the land by culling trees. Others show cattle grazing in newly cleared land. In The Land of the Golden Fleece (1926) a flock of sheep confidently graze in a valley sheltered by the Grampians.

Arthur Streeton Land of the Golden Fleece 1926.

oil on canvas, 92.3 x 146 cm Private collection, Sydney.

Photo: Jenni Carter, AGNSW

Arthur Streeton Land of the Golden Fleece 1926.

oil on canvas, 92.3 x 146 cm Private collection, Sydney.

Photo: Jenni Carter, AGNSW

It is not surprising this painting so effectively encapsulates the sentiment of the conservative establishment: a label on the frame indicates it is the proud possession of one of Australia’s gentleman’s clubs.

Conservatives and conservation

Streeton’s art is also a reminder that conservatives once cared about conservation. He was a passionate advocate for the need to conserve the Australian bush against the timber industry.

Silvan Dam of 1939 is a celebration of the tree clad landscape near his home in the Dandenongs. But in Silvan Dam and Donna Buang, AD 2000, painted the following year, the same subject becomes an apocalyptic vision condemning the then state government’s proposed logging of the forest. Stark, bleached, tree trunks stand against bare rock and denuded mountains.

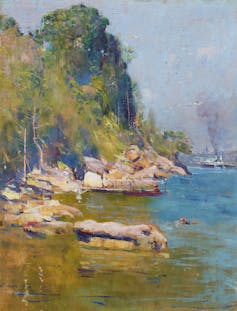

Arthur Streeton Cremorne Pastoral 1895, oil on canvas, 91.5 x 137.2 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, purchased 1895.

Photo: Jenni Carter, AGNSW

Arthur Streeton Cremorne Pastoral 1895, oil on canvas, 91.5 x 137.2 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, purchased 1895.

Photo: Jenni Carter, AGNSW

Streeton’s advocacy for nature over industry was not new. In 1895, when living in Sydney, he painted Cremorne Pastoral, an exquisite landscape of a grassy hill framed by graceful trees and Sydney Harbour as a political response to a proposed coal mine.

It is one of many harbour subjects painted in his Sydney years. As the AGNSW is directly opposite Sirius Cove, where Streeton lived in the 1890s, the bias towards this subject matter is understandable. The camp where Streeton, Roberts and others lived during the 1890s recession was built by the Brasch brothers who were active patrons of the arts.

Arthur Streeton From my Camp (Sirius Cove) 1896, oil on plywood, 28 x 21.5 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, bequest of Mrs Elizabeth Finley 1979.

Photo: Jenni Carter, AGNSW

Arthur Streeton From my Camp (Sirius Cove) 1896, oil on plywood, 28 x 21.5 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, bequest of Mrs Elizabeth Finley 1979.

Photo: Jenni Carter, AGNSW

Reuben Brasch supplied the artists with discarded varnished cedar panels from his department store. Their dark tones and elongated shape encouraged Streeton to become more experimental in his composition.

The colours of the harbour of his paintings in this period are almost dazzling in their intense blue of the water and gold of the Sydney sandstone, with flashes of gum tree green.

A further room shows his second Sydney period, after his return from spending some years in England. These are virtuoso pieces, but lack the experimental flair of the earlier works.

His paintings of Coogee Beach, a subject previously painted by Tom Roberts and Charles Conder, deserve a close look as a reminder of how Sydney’s magnificent beaches have been so degraded.

Lack of context

If there is one problem I have with this exhibition, and indeed with all celebrations of the life of a single artist, it is the lack of context. From the beginning, Streeton was praised simply because he was an Australian, born with a natural talent developed with little formal teaching.

But this is not quite true. While he attended evening classes with Frederick McCubbin at the National Gallery School in Melbourne, the young artist met the academically trained Tom Roberts and the sophisticated adventurer Charles Conder.

Streeton’s art developed during his relationship with these more experienced artists. He painted alongside them at Box Hill and Eaglemont. The exhibition includes his Settler’s Camp (1888), a less than successful homage to Tom Roberts’ The Artists’ Camp (1886). Streeton was, however, a fast learner, and by the time he participated in the 9 by 5 Impressions exhibition, was their equal.

Arthur Streeton Settler’s Camp 1888 oil on canvas, 86.5 x 112.5 cm Private collection, Jugiong, NSW.

Photo: Brenton McGeachie for AGNSW

Arthur Streeton Settler’s Camp 1888 oil on canvas, 86.5 x 112.5 cm Private collection, Jugiong, NSW.

Photo: Brenton McGeachie for AGNSW

The wall of Streeton’s paintings from that most radical of all Australian art exhibitions is a joy. Conder’s influence can be seen in many of Streeton’s earlier paintings, especially in his Symbolist works and in The Railway Station, Redfern (1893), a painting that successfully quotes Departure of the Orient – Circular Quay (1888).

Arthur Streeton The Railway Station, Redfern 1893 oil on canvas, 40.8 x 61 cm.

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, gift of Lady Denison 1942.

Photo: Jenni Carter, AGNSW

Arthur Streeton The Railway Station, Redfern 1893 oil on canvas, 40.8 x 61 cm.

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, gift of Lady Denison 1942.

Photo: Jenni Carter, AGNSW

‘Smike’

The clearest indication of Streeton’s position in the early hierarchy of these brothers of the brush lies in the nickname bestowed on him by the dogmatic Roberts (aka “Bulldog”). Streeton was called “Smike”, after Nicholas Nickleby’s amiable but feeble-minded acolyte.

Arthur Streeton’s later career serves as a repudiation of that assessment. Travel broadened his perspective. He relished the exoticism of Egypt, where magical architecture took the place of gum trees. After initially being intimidated by the sophistication, class system and muted light of England, he did eventually achieve modest success in the centre of the empire.

At the end of World War I, he returned to Australia for real fame and fortune. In 1937, he became the only one of the artists who painted at Heidelberg to be honoured with a knighthood.

The last Arthur Streeton exhibition, curated by Geoffrey Smith for the National Gallery of Victoria in 1995, was shown in other state galleries. This much larger exhibition will not travel.

It is, however, on view throughout summer until February 14 2021. It is well worth the effort of an interstate trip for those newly liberated from quarantine.

Authors: Joanna Mendelssohn, Principal Fellow (Hon), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, University of Melbourne