Aged care isn't working, but we can create neighbourhoods to support healthy ageing in place

- Written by Melanie Davern, Senior Research Fellow, Director Australian Urban Observatory, Deputy Director (Acting) Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University

This article is part of our series on aged care. You can read the other articles in the series here.

In 2020, the coronavirus pandemic has exposed issues and inequities across society. How we plan for ageing populations and older people is one critical issue that has been neglected for decades. Fresher-faced youth and families have become the demographic focus of increasingly short-term electoral cycles, reinforcing a deep-seated prejudice against ageing and older people.

If Gandhi is right, and the true measure of a society can be found in how we treat the most vulnerable, then Australia has a lot to learn from the 683 deaths from COVID-19 in residential aged care this year. Australia needs a radical shift to policies that better support ageing in place — that is, in their own homes — rather than relying so heavily on underfunded and poorly resourced residential aged care.

Residential aged care populations are growing, with 70% of facilities located in major cities and 30% in regional areas. These facilities and current policies are failing our older people as identified by the current Royal Commission into Aged Care. Reform is needed now.

However, residential aged care is only part of the problem of failing to plan adequately for ageing. Neoliberal policies have turned the ageing population into a growing consumer market while filial piety or family caring becomes rarer as economic and social pressures on working families (their adult children) become greater.

Caring for older family members is becoming rarer in Australia, but remains common practice in Asia.

Chayatorn Laorattanavech/Shutterstock

Caring for older family members is becoming rarer in Australia, but remains common practice in Asia.

Chayatorn Laorattanavech/Shutterstock

Read more: Asian countries do aged care differently. Here's what we can learn from them

These trends have reinforced health inequities. More than 100,000 people are on the waiting list for in-home support package funding. Over the past two years, 28,000 people have died before receiving any funding.

Older women are particularly vulnerable. In 2007, 75% of women aged over 70 had no superannuation (with superannuation beginning in the 1980s). Two-thirds of residents in aged care were women.

We need to shift the conversation on ageing to healthy ageing and creating environments that better support ageing in place. Age-friendly places aren’t just good for older people. They also support the needs of children, people with a disability and everyone else in a community.

Read more: 'Ageing in neighbourhood': what seniors want instead of retirement villages and how to achieve it

The 50-year-old child-friendly cities movement has increasingly emphasised how the features of a city that make it safe, healthy and accommodating for its most vulnerable citizens can also make it much more liveable for everyone.

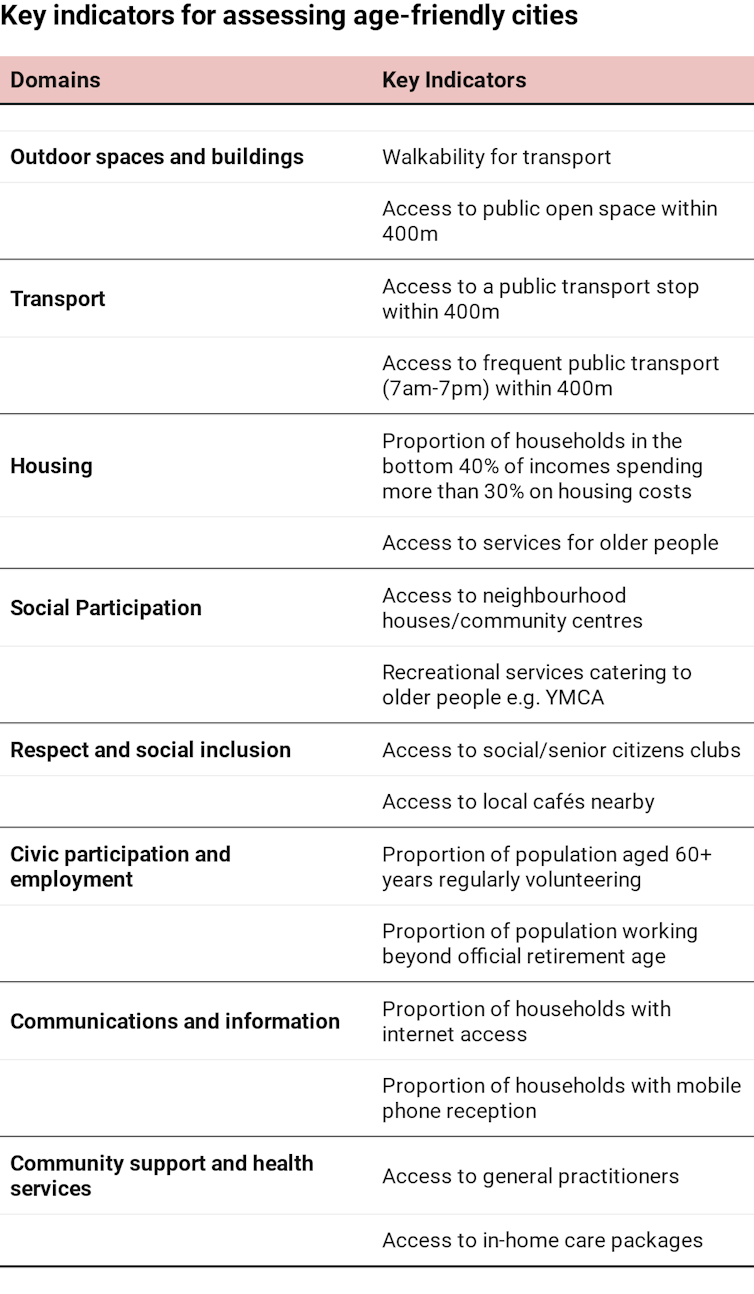

In recent research we looked at how the World Health Organisation’s Global Age-Friendly Cities Guide can be applied in local planning. The aim was to develop practical tools to help policymakers and planners assess the age-friendliness of local neighbourhoods. This included the use of spatial indicators to measure the eight domains of the Age-Friendly Cities framework.

Spatial indicators investigating the relationship between health and place are created using geographic information systems (GIS) to map the presence of features within a local area. We have suggested key indicators that can be created and mapped using desktop analysis to understand how age-friendly local spaces are.

Author provided

One of the most striking features is that many of these suggested measures are important for everyone living locally and not just older people. Examples include good walkability, public open spaces, public transport, affordable housing, local services, cafes, doctors and internet connectivity. Others are age-specific such as in-home aged care.

Most importantly, all of these factors are essential ingredients of healthy and liveable communities. Together, they support better health and well-being outcomes for all. We have mapped many of the suggested measures of age-friendly communities in the Australian Urban Observatory.

Read more:

How do we create liveable cities? First, we must work out the key ingredients

The use of additional technology such as sensor and robot technology should also be considered in future community and housing design, but this depends on household internet access. That can be a problem, particularly in regional and remote areas where populations are ageing rapidly and fewer aged-care places are available.

Some of these indicators might not necessarily be feasible for all regional and rural communities. Many regional communities have reduced access to services. However, these indicators still provide an important starting point for discussions with diverse rural older people about what is important and what constitutes reasonable access within their community.

Read more:

The average regional city resident lacks good access to two-thirds of community services, and liveability suffers

If we have learnt anything from this difficult year, then post-COVID recovery must include a broader approach to ageing that extends beyond residential aged care to a focus on healthy ageing. That means better support for people to age in place.

Age-friendly communities enable older people to continue to make significant economic and social contributions to families and communities. However, this can’t occur unless local places plan for all ages and abilities from the beginning.

Author provided

One of the most striking features is that many of these suggested measures are important for everyone living locally and not just older people. Examples include good walkability, public open spaces, public transport, affordable housing, local services, cafes, doctors and internet connectivity. Others are age-specific such as in-home aged care.

Most importantly, all of these factors are essential ingredients of healthy and liveable communities. Together, they support better health and well-being outcomes for all. We have mapped many of the suggested measures of age-friendly communities in the Australian Urban Observatory.

Read more:

How do we create liveable cities? First, we must work out the key ingredients

The use of additional technology such as sensor and robot technology should also be considered in future community and housing design, but this depends on household internet access. That can be a problem, particularly in regional and remote areas where populations are ageing rapidly and fewer aged-care places are available.

Some of these indicators might not necessarily be feasible for all regional and rural communities. Many regional communities have reduced access to services. However, these indicators still provide an important starting point for discussions with diverse rural older people about what is important and what constitutes reasonable access within their community.

Read more:

The average regional city resident lacks good access to two-thirds of community services, and liveability suffers

If we have learnt anything from this difficult year, then post-COVID recovery must include a broader approach to ageing that extends beyond residential aged care to a focus on healthy ageing. That means better support for people to age in place.

Age-friendly communities enable older people to continue to make significant economic and social contributions to families and communities. However, this can’t occur unless local places plan for all ages and abilities from the beginning.

Authors: Melanie Davern, Senior Research Fellow, Director Australian Urban Observatory, Deputy Director (Acting) Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University