We have enough electorates named after dead white men. It's time we chose a woman instead

- Written by Clare Wright, Professor of History, La Trobe University

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

What’s in a name? A rose might very well smell as sweet if it was called a turnip, but clearly there is more cultural cache invested in nomenclature than Shakespeare would have us believe.

Why else would our forefathers have been so intent on reserving the lion’s share of geographic names in Australia for men if there was not real value in the symbolic real estate?

Why are there so many streets, buildings, bridges, public institutions and private firms named after dudes, and not women?

This cavernous gender gap in public naming practices is precisely why there should be intense scrutiny of the Australian Electoral Commission as it designates a new federal electorate later this month.

The AEC is currently taking public submissions on the name for the new electorate, which is being created in Victoria in 2021 due to a federal redistribution.

Gender equality activists (including, I hope, some of those fabled Male Champions of Change) are busy compiling extensive lists of women, including Indigenous women, who meet the AEC’s criteria for naming divisions: that is, deceased Australians who have rendered outstanding service to their country.

Aboriginal activist Margaret Tucker is one name worth considering for the new electorate.

State Library of New South Wales

Aboriginal activist Margaret Tucker is one name worth considering for the new electorate.

State Library of New South Wales

Place names have always been a means for exerting power

Like statues and monuments, we’ve been taught to treat official names with veneration. As New Yorker journalist Hua Hsu has argued about statues to historical figures in the wake of Black Lives Matters protests,

we are also taught to read them as unitary and their message as unified, rooted in consensus.

We are rarely encouraged to consider whose names — and whose stories and histories — are silenced in the christening process.

Geographic place names have also long been a means for exerting power.

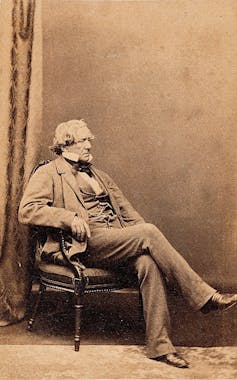

William Charles Wentworth has a federal electorate, town, streets, buildings and even a waterfall named after him.

Wikimedia Commons

William Charles Wentworth has a federal electorate, town, streets, buildings and even a waterfall named after him.

Wikimedia Commons

Recasting a mountain, river or plain from its Indigenous designation to a European name is one of the first and most enduring acts of colonial dispossession. Ensuring those European names belong to exalted or aspirational men is patriarchy’s way of pissing on the post of dominion.

And so it was that when the new Australian nation branded its first federal electorates in 1901 for the 75 House of Representative seats, not one was named after a European woman, let alone a First Australian.

Wentworth, Lang, Oxley, Parkes, Kennedy, Cowper, yes. But not Goldstein, Lee, Windeyer or Wolstenholme — all women who had contributed to the successful inauguration of the Federation. (Look them up.)

Just 11% of electorates named after women

But what about the naming of electorates more recently, in the supposedly more enlightened modern Australia that has witnessed two waves of feminism and – if you believe the Murdoch media — a tsunami of political correctness?

Women’s names are still disproportionately unrepresented. At a federal level, 114 out of the current 150 House seats are named after one or more people. Eighty-nine are named after a man and eight are jointly named for a husband and wife (for example, Lyons) or a family. A mere 17 — or 11% — are named after a woman.

Perhaps even more remarkable, only six electorates bear the name of a First Nations person.

Of those original Federation electoral division names, 36 remain.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Wauba Debar, an Indigenous swimmer from Tasmania who saved her captors

In a nation that claims to value equality and fairness, these numbers are simply not good enough. (Neither are they inevitable: in New Zealand, where seats are exclusively given place names, 37 of 71 have Maori names.)

Electoral boundaries ebb and flow according to demographic fluctuations, but for the names of divisions to reflect our current values when it comes to gender parity — not to mention cultural diversity — will take leadership and commitment on the part of the AEC.

The AEC’s most recent fails: Monash and Bean

The AEC’s most recent opportunity to level the scales of commemorative justice was an abject failure.

Two years ago, the AEC reviewed the federal seat of McMillan, which was first proclaimed in 1949 and encompasses the region of Gippsland in Victoria. The seat was named after colonial “explorer” Angus McMillan, who is now widely acknowledged as the perpetrator of massacres of the Gunaikurnai people. Even Wikipedia calls McMillan “a mass murderer”.

Many Gippsland residents and other civic-minded folk tendered the names of suitable women to help erase McMillan’s sullied legacy. These were all rejected in favour of the electorate’s new name: Monash.

As co-founder of the Honour a Woman campaign, Ruth McGowan lamented in an email to me

a freeway, a university, a local council and a hospital were not enough for the good general.

Nobody disputes John Monash’s valour, but seriously? Come on Australia.

The list of places named after John Monash, Australian military commander, is extensive.

Wikimedia Commons

The list of places named after John Monash, Australian military commander, is extensive.

Wikimedia Commons

Similarly, the creation of a third Commonwealth electorate in Canberra in 2018 witnessed the birth of the division of Bean, honouring the memory of Australian Imperial Force war correspondent Charles Bean.

(Ironically, one of the many objections to the Bean nomination focused on his anti-Semitic comments about Monash during the first world war.)

Was the problem the AEC didn’t receive public support for or suggestions of names of worthy female and Indigenous citizens? Of course not. There were plenty. They were simply overlooked.

Some suggestions of meritorious women for the AEC

Fortunately, we now have another chance to circumvent what Kim Rubenstein, the co-director of the 50/50 By 2030 Foundation, and law student Katrina Hall have pointed out is

effectively a system of affirmative action in favour of men.

The 2021 Victorian redistribution could see the AEC recognise the political and civic leadership of such women as Margaret Tucker, Eleanor Harding, Zelda D'Aprano, Joan Kirner and, of course, the woman who smashed a galaxy of glass ceilings, Susan Ryan.

Pulling down statues is one way to make a statement about the ruins of history. Naming places is an equally powerful — and arguably more creative and cohesive — way of demonstrating, as Hsu puts it,

whether a nation’s story is finished or a work in progress.

The 2021 redistribution will test the AEC’s mettle: instrument of the Canberra boys’ club or, as its mission statement asserts, independent electoral service which meets the needs of the Australian people.

All of the people. Not half of them.

Authors: Clare Wright, Professor of History, La Trobe University