'You wake up with lab-engineered coffee': how our imaginations can help decide Earth's future

- Written by Michelle Lim, Senior Lecturer, Macquarie Law School, Macquarie University

There’s no shortage of scientific studies projecting a bleak future for the planet and her people, but none have led to real change. It’s clear we need better ways to envisage the futures we want.

Take, for example, the current review of Australia’s federal environment law. Among its recommendations are that developers consider the effect of their project on “specified climate change scenarios” — essentially computer-generated models of the future. These models are important. But achieving a radically different tomorrow will require more than a purely technocratic approach.

As we argue in our recent paper, our imaginations allow us to engage with emotions that motivate action, such as hope, fear and grief. Can we imagine a future with no koalas or orange-bellied parrots or wollemi pines? Or of bushfires that destroy the natural wonders of our childhoods?

Storytelling can help in this task. In the following vignettes, we’ve imagined three possible futures for Australia. They involve different challenges, trade-offs and worldviews. We hope these stories stimulate new ways to consider the consequences of our current decisions and actions. So now, imagine you are in the year 2050 …

Can we imagine a future of childhood wonders lost?

Shutterstock

Can we imagine a future of childhood wonders lost?

Shutterstock

1. Basic needs

You sit in a communal kitchen as you sip your low-food-mile oat latte. You watch the news through a holographic vid-cast floating beside you.

Governments and societies have prioritised equality and social welfare over consumerism and industrialisation. The myth of trickle-down economics has been exposed. Countries have turned to localised food production. Reduced consumption, trade and travel have caused carbon emissions to flatline, but it may be too little too late.

Read more: The Morrison government wants to suck CO₂ out of the atmosphere. Here are 7 ways to do it

Your vid-cast tells of winter bushfires in Tasmania and water shortages in all Australian capital cities. You wonder if more spending on technological innovation might have averted these crises.

Nature considered “useful” is doing well. Brisbane’s restored mangroves are flourishing; the city no longer floods, even with sea-level rise. But there is little funding to protect wildlife, and iconic species such as mountain pygmy possums are extinct.

Would better technology have averted catastrophic bushfires?

Warren Frey/Tasmanian Fire Service

Would better technology have averted catastrophic bushfires?

Warren Frey/Tasmanian Fire Service

2. Wildlife rules

You wake up with lab-engineered coffee, then eat breakfast cereal grown at an indoor climate-controlled farm.

You log onto the annual Australasian Conservation Summit. A virtual reality tour takes you to the Great Western Sydney Reserve. There, koalas shipped from Kangaroo Island brought local populations back from the brink. Data from their geo-location tags confirm they now occur across their historic range.

You welcome preservation of this iconic species. But the region’s traditional Dharug clans were not consulted in setting up the reserve. You wonder why they continue to be excluded from walking the Country of their ancestors.

Australia has a significant wildlife-conservation sector, supported by the military, which has created many “green” jobs. But society as a whole is disconnected from nature: most people now experience it via zoos and tree museums.

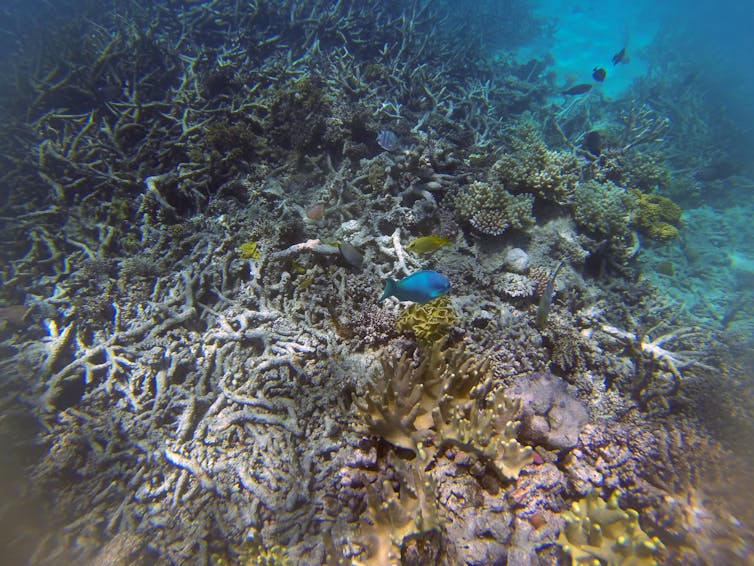

Some wildlife species may be thriving, but the Great Barrier Reef is not. Global heating is worsening and the burning of fossil fuels continues. Successive years of extreme bleaching has left the reef all but decimated.

Under one scenario, the Great Barrier Reef has been decimated.

Under one scenario, the Great Barrier Reef has been decimated.

3. Climate first

You munch breakfast from locally farmed oats. As you inject your carbon-neutral caffeine hit into an arm vein, you feel a wave of nostalgia for a good ‘ol long black in a mug.

Thanks to radical technological solutions, the most catastrophic climate impacts have been averted. Global governance is now dominated by the ideologies of the Radical Climate Action Alliance. In 2021, environmental and human rights treaties were revoked in favour of the Climate First Charter.

In one imagined version of the future, wind farms decimate swift parrot numbers.

Markets for Change

In one imagined version of the future, wind farms decimate swift parrot numbers.

Markets for Change

Your Unity BCI (Brain Computer Implant) receives drone footage from the alliance. It shows Australia’s red centre covered in solar farms, agricultural lands swamped by biofuel crops and South Australia’s Flinders Ranges dotted with nuclear reactors.

The clip closes with images of carbon-capturing radiata pines dominating vast landscapes of the Adani and Rocky Hill carbon sanctuaries. You wonder what it’s like inside — carbon sanctuaries are closed to all except the Carbon Rangers. Even Traditional Owners are excluded from the Country they sustained for millennia. Meanwhile, corporations benefit from green energy ventures while social inequality rises.

The Great Barrier Reef no longer suffers from summer bleaching events. But indiscriminately placed wind farms have brought the swift parrot and grey-headed flying fox almost to extinction.

Read more: Renewable energy can save the natural world – but if we're not careful, it will also hurt it

Imagination is key

None of these futures are inevitable. But exploring the logical conclusions of present-day attitudes and decisions can prompt us to ask: what futures do we want?

Together, the three scenarios raise questions such as whether:

revolutionary economic interventions should be used to address social inequality

local biodiversity should be valued only to the extent that it is useful to humans

iconic species and landscapes should be protected through fortress-style conservation, at the expense of local and Indigenous communities and direct climate change action

governments should prioritise climate action above all else, particularly via technological solutions

biodiversity matters only to the extent it can mitigate climate impacts.

Using our imaginations can help us decide the futures we want.

Shutterstock

Using our imaginations can help us decide the futures we want.

Shutterstock

All this matters. Research shows projections of the future shape how problems are understood and communicated, and which strategies are developed to address them.

So how might this apply to the review of Australia’s environment laws? Further reform should involve a range of groups coming together to discuss questions such as: what do we value? What do we want to change? What trade-offs are we willing to make? By collectively deploying our imaginations, we may create better futures for all.

Authors: Michelle Lim, Senior Lecturer, Macquarie Law School, Macquarie University