Review: new biography shows Vida Goldstein's political campaigns were courageous, her losses prophetic

- Written by Marilyn Lake, Professorial Fellow in History, University of Melbourne

Review: Vida: A Woman for Our Time, published by Penguin (Viking imprint)

Australian women were not the first to win the right to vote in national elections. That world-historic distinction belongs to New Zealanders. But they were the first to win, in 1902, both the right to vote and stand for election to the national parliament.

Three Australian women quickly availed themselves of the opportunity. Nellie Martel and Mary Bentley from New South Wales joined Vida Goldstein from Victoria as candidates in the 1903 federal election.

Little is now known of Martel and Bentley, but Goldstein’s contribution to politics has been commemorated in numerous scholarly studies, theses, essays, book chapters and encyclopedia entries, Janette Bomford’s biography That Dangerous and Persuasive Woman, and a federal electorate named in her honour. But historical memory is fickle and we need still to know more about the political history of women in Australia.

Read more: Women's votes: six amazing facts from around the world

Enlivened by speculation

A skilled and prize-winning biographer, Jacqueline Kent brings fresh enthusiasm and focus to her quest to understand Vida’s extraordinary political career and its disappointments in her new biography. Goldstein stood five times for election to the federal parliament and suffered five defeats.

Kent’s previous biography was The Making of Julia Gillard and it seems the painful experiences of our first woman Prime Minister – subject to relentless misogyny and sexist attacks – remain fresh in the writer’s mind.

Penguin

In Kent’s telling, Vida’s story is framed by Gillard’s fate. There are regular references to Gillard’s experiences and the trials of politicians such as Julie Bishop and Sarah Hanson-Young. Thus Vida’s biography becomes a story of continuity, rather than change, with Vida still “a woman for our time”.

Kent’s account is enlivened by speculation. Vida and her activist mother “might very well have attended” the initial meeting of the Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society (VWSS) and “must have known about” the women’s novels then in circulation.

There is also a good amount of authorial displeasure evident. Women speakers had to endure “the tedious jocularity that was de rigueur” for mainstream journalists. The Age newspaper “evidently considered the welfare of women and children to be a trivial matter”.

Some of the most vivid passages in the book sketch the range of forceful personalities in the Melbourne “woman movement” of the late 19th century, who served as Vida’s models and mentors.

Henrietta Dugdale, cofounder of the VWSS was small in stature, but formidable in argument and the author of the radical Utopian novel A Few Hours in a Far-Off Age. Brettena Smyth, “an imposing speaker, being six feet tall and voluminous in figure, with blue shaded spectacles” was also a member of the VWWS, and sold women contraceptives. Annette Bear-Crawford and Constance Stone were cofounders of the Shilling Fund that made possible the Queen Victoria Hospital for Women.

Read more:

'Expect sexism': a gender politics expert reads Julia Gillard's Women and Leadership

Missing chapters

The larger community of the Australian “woman movement” is largely absent from this account.

There are glimpses of Rose Scott and Louisa Lawson in Sydney and Catherine Spence in Adelaide, who could be frosty when confronted by Goldstein’s evident ambition.

In 1902, Goldstein represented “Australasian” women at the First International Woman Suffrage Conference in Washington, DC. Yet Spence, who preceded Goldstein in her informal role as ambassador for Australian women at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and embarked on a lecture tour, offered her successor a long list of contacts and helpful advice.

Scott, Spence, Goldstein and others of their generation were strong advocates of non-party politics for women, convinced they should avoid the male domination of established political parties. Their strong international connections reinforced woman-identified politics. But would enfranchised women vote as a bloc?

While in Boston in 1902, lecturing to a range of women’s groups, Goldstein met a bright young feminist, Maud Wood Park, whom she invited to Australia. When Goldstein hosted Park and her friend Myra Willard in Melbourne in 1909 she introduced them to future Labor Prime Minister Andrew Fisher and a number of Labor women at a tea party at Parliament House.

Elected to government in 1910, in a historic victory assisted by a strong women’s vote, Fisher responded to lobbying from Labor women and introduced the acclaimed Maternity Allowance.

Kent misses the significance of the rise of the labour women’s movement and its part in the 1910 election result.

Penguin

In Kent’s telling, Vida’s story is framed by Gillard’s fate. There are regular references to Gillard’s experiences and the trials of politicians such as Julie Bishop and Sarah Hanson-Young. Thus Vida’s biography becomes a story of continuity, rather than change, with Vida still “a woman for our time”.

Kent’s account is enlivened by speculation. Vida and her activist mother “might very well have attended” the initial meeting of the Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society (VWSS) and “must have known about” the women’s novels then in circulation.

There is also a good amount of authorial displeasure evident. Women speakers had to endure “the tedious jocularity that was de rigueur” for mainstream journalists. The Age newspaper “evidently considered the welfare of women and children to be a trivial matter”.

Some of the most vivid passages in the book sketch the range of forceful personalities in the Melbourne “woman movement” of the late 19th century, who served as Vida’s models and mentors.

Henrietta Dugdale, cofounder of the VWSS was small in stature, but formidable in argument and the author of the radical Utopian novel A Few Hours in a Far-Off Age. Brettena Smyth, “an imposing speaker, being six feet tall and voluminous in figure, with blue shaded spectacles” was also a member of the VWWS, and sold women contraceptives. Annette Bear-Crawford and Constance Stone were cofounders of the Shilling Fund that made possible the Queen Victoria Hospital for Women.

Read more:

'Expect sexism': a gender politics expert reads Julia Gillard's Women and Leadership

Missing chapters

The larger community of the Australian “woman movement” is largely absent from this account.

There are glimpses of Rose Scott and Louisa Lawson in Sydney and Catherine Spence in Adelaide, who could be frosty when confronted by Goldstein’s evident ambition.

In 1902, Goldstein represented “Australasian” women at the First International Woman Suffrage Conference in Washington, DC. Yet Spence, who preceded Goldstein in her informal role as ambassador for Australian women at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and embarked on a lecture tour, offered her successor a long list of contacts and helpful advice.

Scott, Spence, Goldstein and others of their generation were strong advocates of non-party politics for women, convinced they should avoid the male domination of established political parties. Their strong international connections reinforced woman-identified politics. But would enfranchised women vote as a bloc?

While in Boston in 1902, lecturing to a range of women’s groups, Goldstein met a bright young feminist, Maud Wood Park, whom she invited to Australia. When Goldstein hosted Park and her friend Myra Willard in Melbourne in 1909 she introduced them to future Labor Prime Minister Andrew Fisher and a number of Labor women at a tea party at Parliament House.

Elected to government in 1910, in a historic victory assisted by a strong women’s vote, Fisher responded to lobbying from Labor women and introduced the acclaimed Maternity Allowance.

Kent misses the significance of the rise of the labour women’s movement and its part in the 1910 election result.

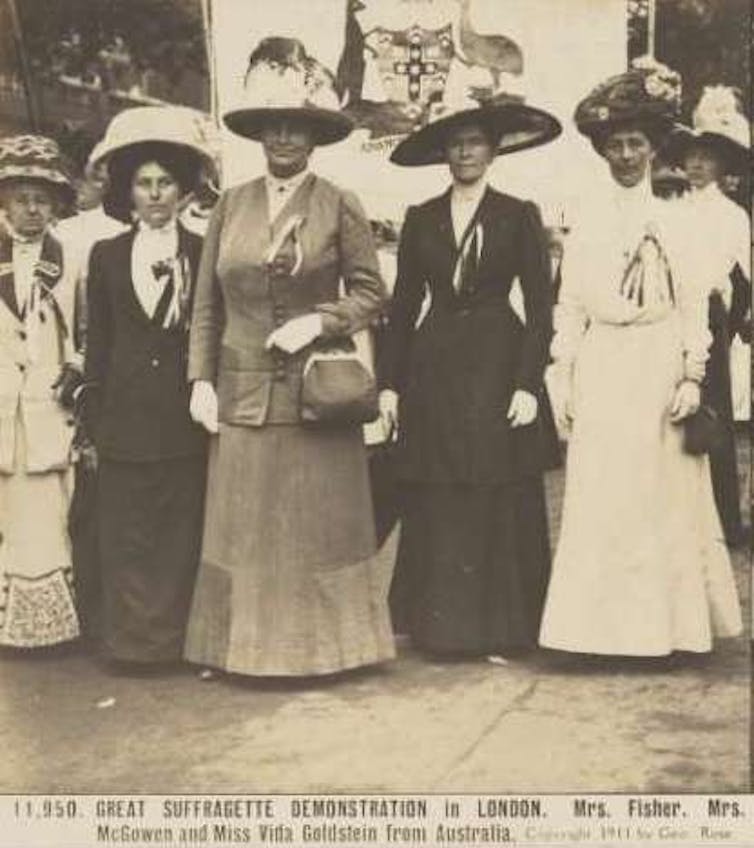

Vida Goldstein (right) takes part in the great suffragette demonstration in London in 1911.

Geo Rose/National Library of Australia

Questions of class

Class divisions mattered, but Kent tends to read Goldstein’s failure as a symptom of sexism, rather than class affiliation.

In the Epilogue, she observes that in the UK and US, Nancy Astor and Jeanette Rankin were quickly elected to Parliament and Congress. In Australia, Dorothy Tangney and Enid Lyons had to wait until 1943 to win seats in the Senate and House of Representatives. Kent doesn’t note, however, that Astor (Conservative) and Rankin (Republican) were party-endorsed candidates, as were Tangney (Labor) and Lyons (Liberal).

Sadly, Vida Goldstein’s series of electoral defeats as a non-party woman candidate would prove prophetic rather than path-breaking.

Goldstein’s courage and endurance qualify her as a woman for our time. But her political strategy of seeking power as an “independent woman candidate” meant she didn’t succeed then or set the most compelling example for aspiring political women today.

Read more:

More than a century on, the battle fought by Australia's suffragists is yet to be won

‘Vote No!’ Vida Goldstein campaigned against WWI conscription as Chair of the Women’s Peace Army and in her newspaper, The Woman Voter.

Vida Goldstein (right) takes part in the great suffragette demonstration in London in 1911.

Geo Rose/National Library of Australia

Questions of class

Class divisions mattered, but Kent tends to read Goldstein’s failure as a symptom of sexism, rather than class affiliation.

In the Epilogue, she observes that in the UK and US, Nancy Astor and Jeanette Rankin were quickly elected to Parliament and Congress. In Australia, Dorothy Tangney and Enid Lyons had to wait until 1943 to win seats in the Senate and House of Representatives. Kent doesn’t note, however, that Astor (Conservative) and Rankin (Republican) were party-endorsed candidates, as were Tangney (Labor) and Lyons (Liberal).

Sadly, Vida Goldstein’s series of electoral defeats as a non-party woman candidate would prove prophetic rather than path-breaking.

Goldstein’s courage and endurance qualify her as a woman for our time. But her political strategy of seeking power as an “independent woman candidate” meant she didn’t succeed then or set the most compelling example for aspiring political women today.

Read more:

More than a century on, the battle fought by Australia's suffragists is yet to be won

‘Vote No!’ Vida Goldstein campaigned against WWI conscription as Chair of the Women’s Peace Army and in her newspaper, The Woman Voter.Authors: Marilyn Lake, Professorial Fellow in History, University of Melbourne