Athletes won't stay silent on politics anymore. But will leagues support their protests if it costs them real money?

- Written by Keith Rathbone, Lecturer, Modern European History and Sports History, Macquarie University

This week, the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks refused to take the court in protest over the police shooting of a Black man in Wisconsin, Jacob Blake, who remains paralysed in hospital.

The players’ boycott immediately threatened the viability of the NBA’s playoffs, endangering the most lucrative part of the season for the league. The players were also risking millions of their own dollars to raise their voices against racism in America.

As the Bucks players later explained in a statement,

We are calling for justice for Jacob Blake and demand the officers be held accountable. […] We encourage all citizens to educate themselves, take peaceful and responsible action, and remember to vote on November 3.

The protest quickly spread across the NBA, where players are increasingly using their social clout to demand action on labour issues from the league and owners. Under pressure from other teams, the league postponed several games. Lakers star LeBron James was quick to remind fans, however, the players were actually boycotting the games — this wasn’t a mere postponement.

And the action quickly spread across the sporting landscape: the WNBA, Major League Baseball and Major League Soccer all cancelled games to protest the Blake shooting. Tennis pro Naomi Osaka refused to play her semifinal match at a tournament, tweeting this:

Remember the backlash against Colin Kaepernick?

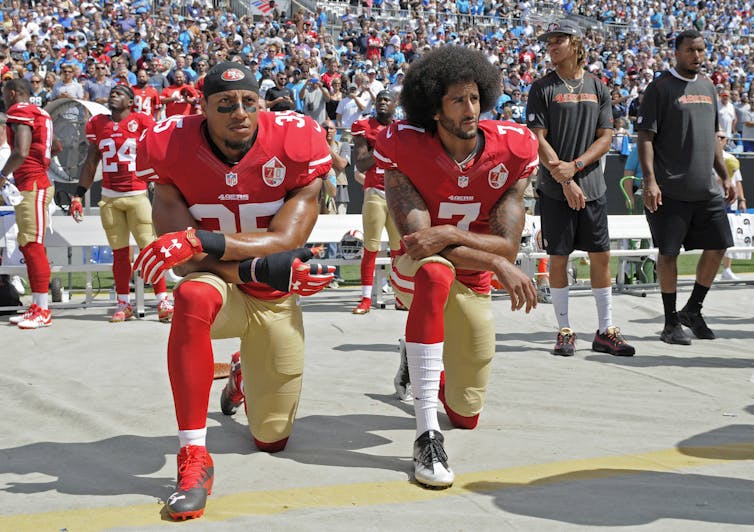

The NBA boycott comes four years to the day that US football player Colin Kaepernick started kneeling before NFL games. The NFL blackballed him due to the protest — and he has yet to return to the league.

Colin Kaepernick has not played in the NFL since his protest movement in the 2016 season.

Mike McCarn/AP

Colin Kaepernick has not played in the NFL since his protest movement in the 2016 season.

Mike McCarn/AP

Since then, however, other American sporting leagues, particularly the NBA, have supported their players’ right to protest and voice their opinions on political issues.

Last month, NBA Commissioner Adam Silver defended players’ right to kneel during the national anthem. The COVID bubble where the playoffs are being held also features Black Lives Matter jerseys, signs and floor decals.

Although the players have voted to resume the playoffs after a day, they made a statement that would have been unthinkable in the sports world just a few years ago.

Despite risking millions of dollars in salary, endorsements and bonuses, many players have shown they are willing to pay the price, potentially even jeopardising their careers, because they are simply fed up with unchecked police violence against people of colour.

As Toronto Raptors guard Fred VanVleet told reporters,

if we’re gonna sit here and talk about making change, then at some point we’re gonna have to put our [manhood] on the line and actually put something up to lose.

Some players are also becoming political in more direct ways. James, for instance, has raised millions to pay off the fines for convicted felons to allow them to vote. Chris Paul of the Oklahoma City Thunder, meanwhile, registered his whole team to vote.

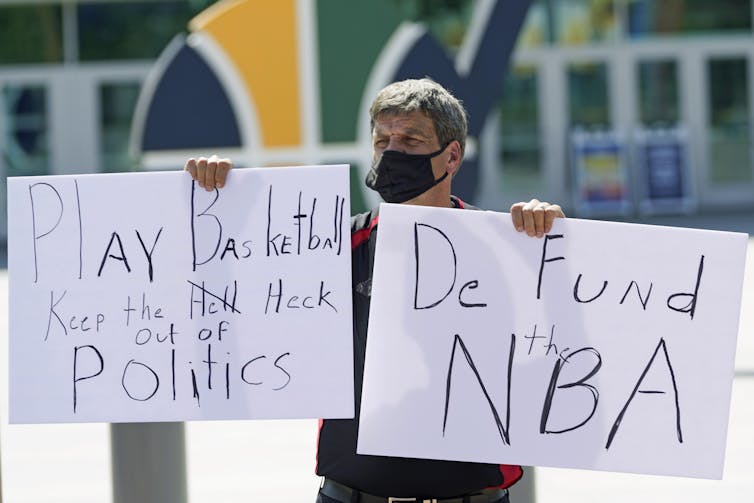

The stoppage in play across sport was in stark contrast to the response to Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling four years ago.

JOHN G. MABANGLO/EPA

The stoppage in play across sport was in stark contrast to the response to Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling four years ago.

JOHN G. MABANGLO/EPA

What happens if the NBA loses money, though?

Whether the NBA continues to stand by players in their protests, however, remains to be seen.

The league reportedly stands to lose upwards of US$1 billion in revenue if the playoffs are cancelled. Not only that, the bubble itself cost the NBA US$170 million just to set up.

Read more: Why US sports stars are taking a knee against Trump

If the playoffs do end early, the relationship between the league and players could very well be broken, possibly leading to a lockout next season. This, in turn, would further devastate the finances of both players and the league.

Trapped between the competing demands of its advertisers, TV partners, owners and players, the NBA has until now remained remarkably silent about the boycott. The big question is how the league will respond if fans start to tune out and the protests ultimately start to cost it money.

Crucially, it should be noted the NBA collective bargaining agreement bans strikes, so in effect, the players’ actions could be in violation of this (though there is some debate over whether this was a “boycott” or a “strike”).

Silver, the NBA commissioner, has been faced by a somewhat similar dilemma before. Last year, Houston Rockets General Manager Daryl Morey tweeted support for the Hong Kong protests, angering the Chinese government to such an extent, the state broadcaster stopped airing NBA games — and still hasn’t resumed.

Silver has said the league could lose as much as US$400 million in revenue from China, yet he still stuck by Morey’s right to express himself.

The future of sport is no doubt political

For many NBA players and coaches, police violence is personal. Some Bucks players have spoken out about their own difficult experiences with the police. Clippers coach Doc Rivers tearfully explained how hard it was loving a country so much that “does not love us back”.

The players have also been supported by many inside the sport. NBA refs are marching in solidarity with the players, while one commentator walked off the set during a live broadcast.

But criticisms are also coming in from other parts of society. Author Juanita Broaddrick tweeted a message directly to James, telling him to “Move to China”, which was liked nearly 35,000 times.

The NBA boycott has angered some fans who want to keep politics out of sport.

Rick Bowmer/AP

The NBA boycott has angered some fans who want to keep politics out of sport.

Rick Bowmer/AP

President Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, meanwhile, said NBA players were

very fortunate that they have the financial position where they’re able to take a night off from work.

But despite the inevitable backlash, the boycott feels like the start of “something big”, to quote one sports columnist.

Taking a knee before a game or raising a fist during a medal ceremony rocked the country, but never before has a league just had to shut it down. Now we have, at least for a day.

In a sign of just how far such politically motivated protests could go, even the National Hockey League, the whitest pro sport in North America, decided to postpone games following Blake’s shooting.

Sports figures won’t stay silent anymore when it comes to politics, nor should they be expected to.

Read more: Is Russia worthy of hosting the World Cup?

Authors: Keith Rathbone, Lecturer, Modern European History and Sports History, Macquarie University