In a land of ancient giants, these small oddball seals once called Australia home

- Written by James Patrick Rule, Palaeontology PhD Candidate, Monash University

When most of us think of the prehistoric past, we envision a world of bizarre, often fearsome giants. From dinosaurs to mammoths and even penguins, life then seemed larger than life today.

Millions of years ago in Australia, giant goannas, kangaroos and diprotodontids (wombat relatives) roamed the landscape. The seas teemed with gargantuan predators such as the infamous “megalodon” shark and so-called giant killer sperm whales.

Fossils from this lost world can be found in sandstone rocks, between five million and six million years old, at Beaumaris – a bayside suburb in Melbourne and one of Australia’s most significant urban fossil sites. Here, fossils of ancient marine animals often wash ashore, eroded out of rocks by the tides.

However, some of these fossils are now revealing “jumbo” was not the only size for extinct animals. Our team’s research, published today in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, reports nine new seal fossils from Beaumaris, which we suspect came from nine different individuals.

The findings paint a picture of a relatively small animal, making its way through a world of giants.

Read more: Meet the giant wombat relative that scratched out a living in Australia 25 million years ago

More than doubling the seal fossil record

Melburnians have been collecting fossils from Beaumaris for more than 100 years. Yet it continues to produce remarkable and scientifically important finds.

The fossils we studied were found on the foreshore of Beaumaris, Melbourne.

Erich Fitzgerald, Author provided

The fossils we studied were found on the foreshore of Beaumaris, Melbourne.

Erich Fitzgerald, Author provided

This includes extremely rare fossils of animals such as seals. Previously, scientists had studied only one seal fossil from this site.

The nine new fossils detailed in our research were collected and donated to Museums Victoria by local scientists and citizen scientists over the past 88 years. They have more than doubled the known fossil record of seals in Australia.

These fossils represent the oldest evidence of seals in Australia and were identified as “true seals”, a group mostly known from the Arctic and Antarctic. True seals belong to a different group to Australia’s fur seals and sea lions (eared seals), which only arrived in the region about 500,000 years ago.

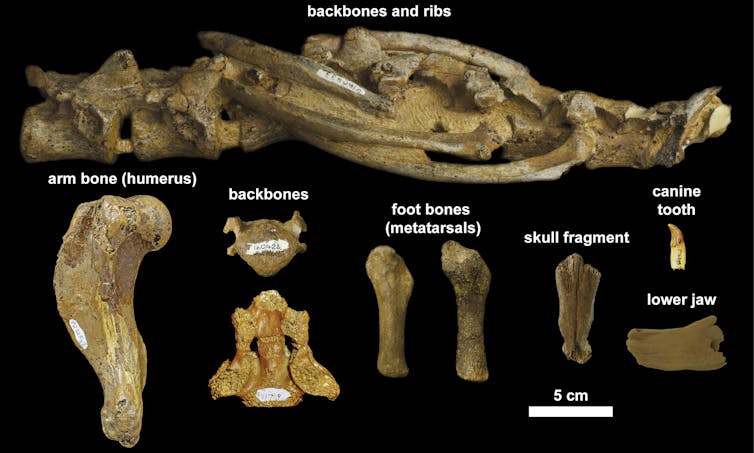

In total, we found nine seal fossil specimens from Beaumaris, from potentially nine different individuals.

Erich Fitzgerald and James Rule, Author provided

In total, we found nine seal fossil specimens from Beaumaris, from potentially nine different individuals.

Erich Fitzgerald and James Rule, Author provided

In particular, one of the fossils we identified is a monachine (a southern true seal). Today, these are represented by animals such as leopard or elephant seals in the Southern Ocean surrounding the Antarctic, to which they are related.

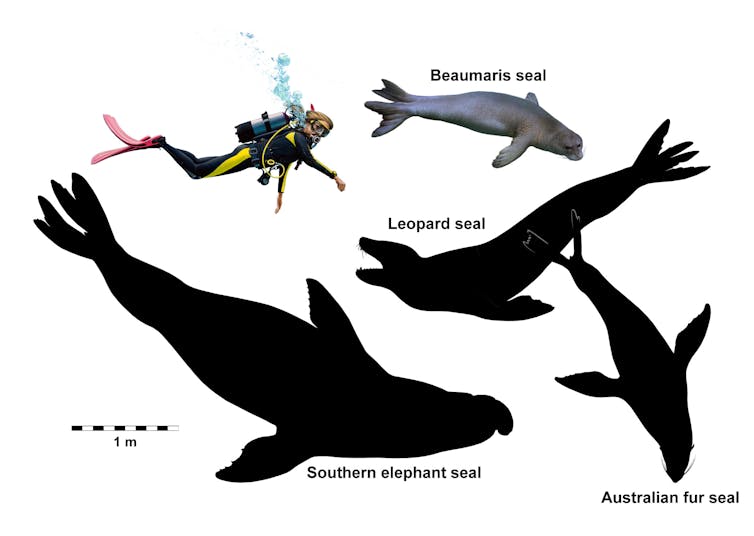

Size estimates found the Beaumaris monachines to have been quite small, at only 1.7 metres long. This is similar to the size of today’s Northern Hemisphere seals such as the harbour seal.

However, the Beaumaris seal’s living relatives are much larger – usually 3m long or more. Modern leopard seals can grow to more than 3m long, while elephant seals can reach up to a gigantic 5m in length.

Most fossil whales found at Beaumaris are also smaller than their living counterparts.

This is the opposite trend to many other animal groups with fossils found there, including some sharks and seabirds, wherein the extinct animals were much larger than those alive today.

The extinct Beaumaris seal was much smaller than its living relatives today.

Art by Peter Trusler, Author provided

The extinct Beaumaris seal was much smaller than its living relatives today.

Art by Peter Trusler, Author provided

An uncertain future for marine life

Why is finding small seals at Beaumaris important?

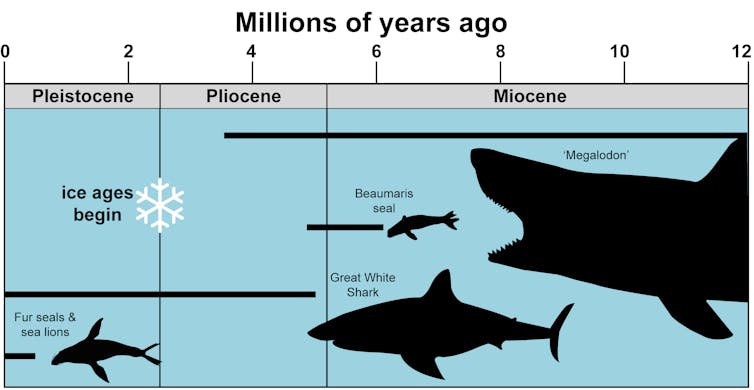

Five million years ago, before the ice ages, the average annual temperature in southeast Australia was about 2–4°C warmer than it is today, with sea levels up to 25m higher.

These warmer oceans supported a greater diversity of marine megafauna than today, with longer but less energy-efficient food chains. These chains only had room for a few large top predators, such as megalodon sharks. And this may have limited the size of other top predators, including seals.

This chart shows the history of seals’ size evolution in Australia, compared to large sharks.

Peter Trusler and James Rule, Author provided

This chart shows the history of seals’ size evolution in Australia, compared to large sharks.

Peter Trusler and James Rule, Author provided

This is important. It suggests the large size of Antarctic seals living in the Southern Ocean today is due to colder oceans with more energy-efficient food chains, in which more food is available for marine animals.

If climate change continues to warm the oceans, food chains may once again start to become less energy efficient, resulting in a loss of the resources today’s large seals rely on for survival.

The discovery of seal fossils at Beaumaris has implications for not only unlocking the past, but also for contextualising the future.

It shows the biodiversity and ecology of marine megafauna off southern Australia originated during the long-term transition from a warmer to colder world – a process that only recently began changing trajectory.

To this day, the fossil site at Beaumaris continues to reveal scientifically important finds, thanks to members of the public working with scientists from Museums Victoria.

Read more: The Meg: the ocean's fossil record is a treasure trove for potential monster movies

Authors: James Patrick Rule, Palaeontology PhD Candidate, Monash University