Early access to super doesn’t justify higher compulsory contributions

- Written by Brendan Coates, Program Director, Household Finances, Grattan Institute

A big part of the Morrison government’s response to COVID-19 has been allowing people early access to their superannuation.

Australians who have claimed hardship have applied for A$30.7 billion to date.

This has been happening in an environment in which compulsory super contributions are set to climb from 9.5% of wages to 12% over the next five years starting in July next year.

Many in the super industry and former prime minister Paul Keating argue that these scheduled increases have to go ahead in order to repair the damage done to the super balances of Australians who withdrew super.

However, new Grattan Institute modelling shows most Australians will have a comfortable retirement even if they have spent some of their super early.

Withdrawals cost less than you might think

Under the government’s scheme, people who have lost their job or had their hours cut or trading income cut by 20% or more were allowed to withdraw up to $10,000 from their super between April and June, and up to another $10,000 between July and December.

More than 500,000 have cleared out their super accounts entirely. Treasury expects total withdrawals to reach $42 billion.

Retirement incomes will fall for workers who withdraw their super, but not by as much as might be thought.

The pension means test means that the government, via higher pension payments, makes up much of what’s lost.

Read more: Why we should worry less about retirement - and leave super at 9.5%

The result is that a typical (median income) 35 year old who takes the full $20,000 would see their retirement balance fall by around $58,000 but would see their actual income over retirement would fall by only $24,000.

Put another way, in retirement that worker would earn 88% of their pre-retirement income instead of 89%.

Retirees need less to live on than while working.

Both are well above the 70% post-tax replacement benchmark used by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Mercer Global Pension Index to determine how much is needed in retirement.

Workers on median incomes who withdraw the full $20,000 will remain well above that benchmark, even with compulsory super contributions staying where they are, at 9.5% of salary.

The very highest and very lowest income earners will receive less extra pension to compensate, and will have less of a cushion.

For most, 9.5% will remain enough

Defaults such as compulsory contributions have to be set so they work for most of the population.

While around one in five Australians have accessed their super early, four in five have not. Policy makers can only justify forcibly lowering someone’s living standards during their working life – by lifting compulsory super – if they are protecting that person from an even worse outcome in retirement.

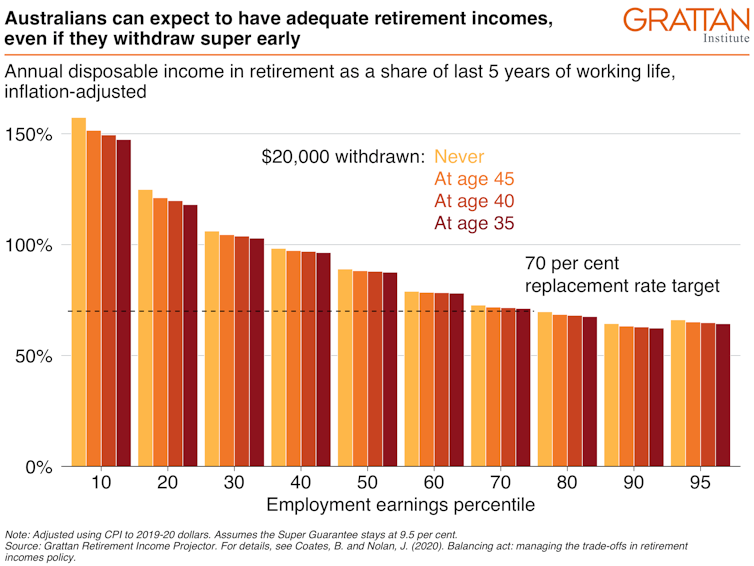

Our modelling shows workers on all but the highest incomes will retire on incomes at least 70% of their pre-retirement post-tax earnings, the so-called replacement standard.

Retirees need less to live on than while working.

Both are well above the 70% post-tax replacement benchmark used by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Mercer Global Pension Index to determine how much is needed in retirement.

Workers on median incomes who withdraw the full $20,000 will remain well above that benchmark, even with compulsory super contributions staying where they are, at 9.5% of salary.

The very highest and very lowest income earners will receive less extra pension to compensate, and will have less of a cushion.

For most, 9.5% will remain enough

Defaults such as compulsory contributions have to be set so they work for most of the population.

While around one in five Australians have accessed their super early, four in five have not. Policy makers can only justify forcibly lowering someone’s living standards during their working life – by lifting compulsory super – if they are protecting that person from an even worse outcome in retirement.

Our modelling shows workers on all but the highest incomes will retire on incomes at least 70% of their pre-retirement post-tax earnings, the so-called replacement standard.

The graph shows that many low-income workers will receive a pay rise when they retire, even if they withdraw the full $20,000 from super.

Of course, some low-income Australians remain at risk of poverty in retirement – especially those who rent. They struggle even more before they retire.

Boosting rent assistance would do far more to help them than would higher compulsory super contributions, and would do less to make them poor while working.

COVID is another reason to keep super where it is

Before COVID-19, there were good reasons to abandon the planned increases in compulsory super; among them that it would do little to boost the retirement incomes of many Australians, that it would drain government tax revenues and widen the gender gap in retirement incomes.

COVID provides another reason. Previous Grattan work has shown that higher super comes at the expense of future wage increases. It’s a conclusion the Reserve Bank has also reached.

Read more:

Think superannuation comes from employers' pockets? It comes from yours

The retirement income review at present with the government is likely to come to the same conclusion.

Increasing compulsory super contributions in the midst of a deep recession would slow the pace of recovery. And that would be bad news for all Australians, regardless of how much we end up with in super.

The graph shows that many low-income workers will receive a pay rise when they retire, even if they withdraw the full $20,000 from super.

Of course, some low-income Australians remain at risk of poverty in retirement – especially those who rent. They struggle even more before they retire.

Boosting rent assistance would do far more to help them than would higher compulsory super contributions, and would do less to make them poor while working.

COVID is another reason to keep super where it is

Before COVID-19, there were good reasons to abandon the planned increases in compulsory super; among them that it would do little to boost the retirement incomes of many Australians, that it would drain government tax revenues and widen the gender gap in retirement incomes.

COVID provides another reason. Previous Grattan work has shown that higher super comes at the expense of future wage increases. It’s a conclusion the Reserve Bank has also reached.

Read more:

Think superannuation comes from employers' pockets? It comes from yours

The retirement income review at present with the government is likely to come to the same conclusion.

Increasing compulsory super contributions in the midst of a deep recession would slow the pace of recovery. And that would be bad news for all Australians, regardless of how much we end up with in super.

Authors: Brendan Coates, Program Director, Household Finances, Grattan Institute