From superheroes to the clitoris: 5 scientists tell the stories behind these species names

- Written by Anthea Batsakis, Deputy Editor: Environment + Energy, The Conversation

Weaving creative, heartfelt or even risqué words into the formal Latin names for new species has long been common in taxonomy — the science of classifying flora and fauna.

An 18th century botanist, for example, named a genus of flower “Clitoria” after the human clitoris, and some scientists have named species after celebrities, or their loved ones.

The ‘Deadpool fly’ went viral last week for its striking resemblance to the Marvel superhero.

Isabella Robinson/CSIRO

The ‘Deadpool fly’ went viral last week for its striking resemblance to the Marvel superhero.

Isabella Robinson/CSIRO

In any case, naming a species is the first step to understanding and protecting our precious biodiversity. Only 30% of the world’s species have been named and many are lost to climate change, deforestation and introduction of invasive species before ever being known to science.

Here, five experts tell the stories behind species they’ve named or researched, from a Hugh Jackman-esque spider to a tiny crustacean named for the researcher’s partner’s swimming prowess.

Wolverine (Wolf) spider, Tasmanicosa hughjackmani

Volker Framenau

This wolf spider species honours the Australian actor Hugh Jackman, who played Wolverine in the X-Men film series. I named the spider in 2016 after Jackman’s extraordinary artistic skills, and for his numerous philanthropic activities.

Of course, wolf spiders are much more remarkable than wolverines. For example, if you hold a torch or spotlight near your head, their sparkling green eyes reflect back into yours.

At night you might catch its sparkling green eyes reflected in your light.

Volker Framenau, Author provided

At night you might catch its sparkling green eyes reflected in your light.

Volker Framenau, Author provided

They can orientate using polarised light, even in the absence of direct sunshine or moonlight. This allows spiders to position themselves along coastal or riverbank environments, without needing a direct view to water.

The wolverine spider can also “fly” using gossamer threads (their spider silk) to catch the wind. They also use multimodal (visual, chemical, percussive) communication. Their mothers carry their eggs and subsequently often hundreds of young on their back, and they can live without food for more than a year.

Read more: It's funny to name species after celebrities, but there's a serious side too

Butterfly pea, Clitoria ternatea

Michelle Colgrave

The genus name Clitoria, is taken from Latin, meaning “from a human female genital clitoris”. And if you look at the distinctive shape of the flower, you may be able to see why.

The genus of the butterfly pea was named after the human clitoris.

Shutterstock

The genus of the butterfly pea was named after the human clitoris.

Shutterstock

I’ve researched species within this genus, such as Clitoria ternatea, but it was 18th century Swedish botanist Carl von Linne (or Carolus Linnaeus) who named it. Linnaeus is credited with formalising “binomial nomenclature”, the way we name species today. And he was largely responsible for several rather ribald names, including orchids, named Orchis from the Greek word for “testicle”.

Read more: Oh, oh, oh! The clitoris certainly gives pleasure. But does it also help women conceive?

Clitoria ternatea, or the butterfly pea, is a legume originating in Africa, but is now widespread through much of Asia and tropical regions in Australia. It was used in a variety of indigenous medicines throughout Asia ascribed with a range of activities, including anecdotal evidence of their use as an aphrodisiac.

Clitoria ternatea has found numerous uses in Australia as a forage crop for grazing or for soil remediation. It is popular in horticulture for its bright blue flowers, and is revered in India as a holy flower. It’s also widely used in food and beverages — from rice to tea to cocktails and liqueurs.

Butterfly peas can be used for food and beverages, with a striking colour.

Shutterstock

Butterfly peas can be used for food and beverages, with a striking colour.

Shutterstock

More recently, it has been found to offer protection from insect pests, and has been commercialised as Sero-X, an eco-friendly insecticide.

If this sparks your interest, then you might also be interested in Nepenthes species or Amorphophallus titanum!

The Beyoncé fly, Plinthina beyonceae

Bryan Lessard

Naming a species after a celebrity is a creative way to draw attention to a particular creature and taxonomy.

The first species I ever named was a golden horse fly from the Atherton Tableland in Queensland. It was originally collected in 1982, but there were no horse fly experts in the country to identify it, so it was archived in Australian natural history collections for 30 years.

The Beyoncé fly, because Beyoncé is fly.

Bryan Lessard, Author provided

The Beyoncé fly, because Beyoncé is fly.

Bryan Lessard, Author provided

Then, during my PhD in 2012, I immediately recognised it as a new species, and named it after Beyoncé since I was listening to a lot of her music while examining the species under the microscope. The specimens were even collected in the same year she was born!

Plinthina beyonceae, its official name, sparked a global discussion on the importance of flies. And scientists are just starting to realise how important the Beyoncé fly and other horse flies are at pollinating some of our iconic native plants including eucalypts, tea trees and grevilleas.

Since the Beyoncé fly, our team at CSIRO has been more imaginative in naming species. Our PhD student Xuankun Li recently named a species of a winter-loving bee fly with crown of thorn-like spines after the Night King from Game of Thrones. And just last week our undergraduate student Isabella Robinson named a heroic group of assassin flies after Deadpool and other Marvel characters.

Mogurnda mosa

Aaron Jenkins

I’ve been fortunate enough to discover, describe, and name several species new to Western science, including 11 new species of fishes. While many of these critters have legitimately avoided recognition in any language, several have long been known and named by local indigenous people.

So, to say I “discovered” and “named” them is blatantly untrue and pongs of colonial misappropriation of traditional knowledge.

Lake Kutubu, where this fish was discovered.

Ambok1/Wikimedia, CC BY

Lake Kutubu, where this fish was discovered.

Ambok1/Wikimedia, CC BY

About 20 years ago I was the first person to SCUBA dive in Lake Kutubu — an exceptionally clear, high altitude lake in Southern Highlands in Papua New Guinea. As part of this marvellous experience I found several species of fishes new to Western science. One of which was a preferred food fish for the local Foe people, named “mosa” in Foe tokples (local language in Melanesian Pidgin).

In recognition of the tokples name of this species, I simply provided mosa as the species name in my scientific description. This new species is now named Mogurnda mosa in Western science, combining “Mogurnda”, which is an Aboriginal name used in Australia, and the tokples name “mosa”.

The Mogurnda mosa fish, found in Papua New Guinea.

Western Australian Museum Field Guides and Catalogues

The Mogurnda mosa fish, found in Papua New Guinea.

Western Australian Museum Field Guides and Catalogues

This fish is a true indigenous species of Oceania, named to honour the original names of the traditional custodians. But oil and gas drilling around the lake significantly threatens the entire known, critically endangered population. Additional threats include invasive species.

Moody’s swamp amphipod, Kartachiltonia moodyi

Rachael King

Finding tiny crustaceans in unusual places is one of the best parts of my work as a research scientist. I’ve trawled the deep-sea floor on big oceanographic vessels, fished down bore holes in arid deserts, and dug in swamps, seeps and springs in the outback — all in an effort to find new species.

In 2009 my colleague and I travelled to Kangaroo Island and collected specimens from a new site to us — a spring-fed swamp near Rocky River. The specimens ended up being a new genus and species of amphipod, which we called Kartachiltonia moodyi.

The name breaks down roughly as “Karta” for the local Indigenous name of Kangaroo Island, and “chiltonia” for the family (Chiltoniidae) it belongs to.

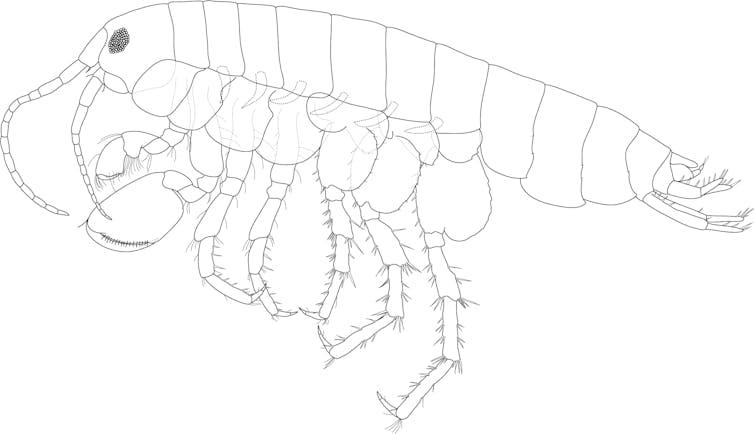

An illustration of the Moody’s swamp amphipod.

Author provided

An illustration of the Moody’s swamp amphipod.

Author provided

The last part to the species name was named after my partner, whose last name is Moody. This animal basically has a whole extra set of gills that no other Australian chiltoniid amphipods had — and my partner was a good competitive swimmer in his youth. It made perfect sense to me (Phar Lap had a bigger heart, right?!).

He’s quite happy to have a species named for him, and also happy any similarities weren’t based on something like a giant head or weirdly shaped feet (neither of which he, or the amphipod, has).

And with the recent bushfires roaring through this swamp area on Kangaroo Island, we have been on tenterhooks to see if the species managed to survive. This week we’ve managed to get some samples from nearby, and it’s looking good, but I won’t know for sure until I get them under a microscope.

Authors: Anthea Batsakis, Deputy Editor: Environment + Energy, The Conversation