Guide to the Classics: how Marcus Aurelius' Meditations can help us in a time of pandemic

- Written by Matthew Sharpe, Associate Professor in Philosophy, Deakin University

Marcus Aurelius was no stranger to pandemics. For 16 years of his reign as Roman Emperor (161-180 CE), the empire was ravaged by the Antonine plague, which took five million lives.

It was during this period that the philosopher king penned a series of “notes to himself”. Unpublished during his lifetime and found untitled with his mortal remains, this work has come to be called his Meditations.

Described by philosopher and biblical scholar Ernst Renan as “a gospel for those who do not believe in the supernatural,” the Meditations is a series of fragments, aphorisms, arguments, and injunctions. They were written at different moments in the final years of Marcus’ life.

As its opening book makes clear, Marcus had been converted to the philosophy of Stoicism at a young age. Like its great ancient competitor Epicureanism, Stoicism was more than a set of doctrines explaining the world and human nature.

Stoicism also demanded from its students a transformed attitude to life. Many Stoic texts prescribe practical exercises to reshape how a person responds to adversity and prosperity, insults, illness, old age, and mortality.

This practical dimension to Stoic philosophy underlies its extraordinary global rebirth in the new millennium, even before COVID-19. So, what can Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations tell us today, in our time of pandemic?

Read more:

Stoicism 5.0: The unlikely 21st century reboot of an ancient philosophy

A kind of lockdown

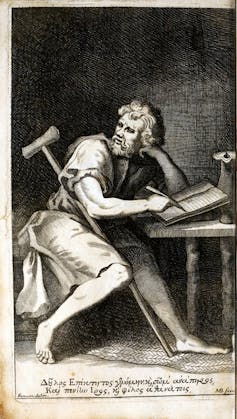

The Meditations comprises over 400 fragments, divided into 12 books. These disparate fragments are shaped by a few core philosophical principles. At the basis of these principles is the fundamental Stoic distinction expressed most clearly by the emancipated slave turned philosopher, Epictetus, whom Marcus greatly admired: that some things depend upon us and others do not.

As its opening book makes clear, Marcus had been converted to the philosophy of Stoicism at a young age. Like its great ancient competitor Epicureanism, Stoicism was more than a set of doctrines explaining the world and human nature.

Stoicism also demanded from its students a transformed attitude to life. Many Stoic texts prescribe practical exercises to reshape how a person responds to adversity and prosperity, insults, illness, old age, and mortality.

This practical dimension to Stoic philosophy underlies its extraordinary global rebirth in the new millennium, even before COVID-19. So, what can Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations tell us today, in our time of pandemic?

Read more:

Stoicism 5.0: The unlikely 21st century reboot of an ancient philosophy

A kind of lockdown

The Meditations comprises over 400 fragments, divided into 12 books. These disparate fragments are shaped by a few core philosophical principles. At the basis of these principles is the fundamental Stoic distinction expressed most clearly by the emancipated slave turned philosopher, Epictetus, whom Marcus greatly admired: that some things depend upon us and others do not.

Epictetus, the crippled slave who became one of Rome’s leading Stoic philosophers.

Wikimedia Commons

In fact, of all the things in the world, we can only directly control what we do, think, choose, desire, and fear.

Everything else, including everything our society tells us that we need to “get a life” – riches, property, fame, promotions – depends on others and on fortune. It is here today and gone tomorrow, and it is usually distributed unfairly.

So to pin our dreams on achieving such things makes our happiness and peace of mind a highly uncertain prospect.

The Stoics propose that what they call “virtue” is the only good. And this virtue consists above all in knowing how best to respond to the things that befall us, rather than fretting about things we cannot control.

For Marcus, all those “goods” that markets trade, and our contemporary advertisements hawk, are “indifferent”. It is what you do with the pleasurable things, and with the difficulties you face, that shapes how happy or unhappy you will be.

It is almost as if Stoicism asks of us a kind of “virtual lockdown”, anticipating the actual one some of us are currently experiencing. The inability to go swimming, or to the football, gym, or movies, is for the Stoic regrettable. But it isn’t devastating. For s/he has weighed such preferable external things at their relative value.

“Wherever it is possible to live, it is possible to live well”, Marcus affirms.

None of us chose the pandemic. But each of us can strive to exercise courage in facing it, generosity in helping others, and resilience before the challenges it presents.

‘Only the present’

“Things do not touch the soul,” Marcus writes: “our perturbations come only from the opinion which is within”. And our opinions can, with hard work, be reformed. For they depend upon us.

This is the Stoic “good news”. Pandemics, bullies, and mischances really can rob us of our money, our jobs, our reputations. If they are malign enough, they affect our physical health. But they cannot change our minds. They cannot make us commit evil actions. They are powerless to even compel us to think resentful or hateful things about our fellows.

If it becomes clear, for instance, that someone has back-stabbed you, Marcus advises:

Pronounce no more to yourself, beyond what the appearances directly declare. It is said to you that someone has spoken ill of you. This alone is told you, and not that you are hurt by it.

If what your insulter has said is true, then change. If what they have said is false, it does not merit your being upset by it. If they have betrayed your trust, the shame and the fault lies with them.

“The best revenge,” Marcus counsels, “is not to become like the wrongdoer”.

Yes, we might reply, but what about truly enormous situations like COVID-19, or the end of a life-shaping relationship, or the illnesses of loved ones?

The Stoic principle of focusing only on what depends upon us operates here too. Worries carry our minds away into the future. Unless we watch ourselves, we can quickly find ourselves imagining the worst – the death of friends and family, a second great depression, the end of a career …

Epictetus, the crippled slave who became one of Rome’s leading Stoic philosophers.

Wikimedia Commons

In fact, of all the things in the world, we can only directly control what we do, think, choose, desire, and fear.

Everything else, including everything our society tells us that we need to “get a life” – riches, property, fame, promotions – depends on others and on fortune. It is here today and gone tomorrow, and it is usually distributed unfairly.

So to pin our dreams on achieving such things makes our happiness and peace of mind a highly uncertain prospect.

The Stoics propose that what they call “virtue” is the only good. And this virtue consists above all in knowing how best to respond to the things that befall us, rather than fretting about things we cannot control.

For Marcus, all those “goods” that markets trade, and our contemporary advertisements hawk, are “indifferent”. It is what you do with the pleasurable things, and with the difficulties you face, that shapes how happy or unhappy you will be.

It is almost as if Stoicism asks of us a kind of “virtual lockdown”, anticipating the actual one some of us are currently experiencing. The inability to go swimming, or to the football, gym, or movies, is for the Stoic regrettable. But it isn’t devastating. For s/he has weighed such preferable external things at their relative value.

“Wherever it is possible to live, it is possible to live well”, Marcus affirms.

None of us chose the pandemic. But each of us can strive to exercise courage in facing it, generosity in helping others, and resilience before the challenges it presents.

‘Only the present’

“Things do not touch the soul,” Marcus writes: “our perturbations come only from the opinion which is within”. And our opinions can, with hard work, be reformed. For they depend upon us.

This is the Stoic “good news”. Pandemics, bullies, and mischances really can rob us of our money, our jobs, our reputations. If they are malign enough, they affect our physical health. But they cannot change our minds. They cannot make us commit evil actions. They are powerless to even compel us to think resentful or hateful things about our fellows.

If it becomes clear, for instance, that someone has back-stabbed you, Marcus advises:

Pronounce no more to yourself, beyond what the appearances directly declare. It is said to you that someone has spoken ill of you. This alone is told you, and not that you are hurt by it.

If what your insulter has said is true, then change. If what they have said is false, it does not merit your being upset by it. If they have betrayed your trust, the shame and the fault lies with them.

“The best revenge,” Marcus counsels, “is not to become like the wrongdoer”.

Yes, we might reply, but what about truly enormous situations like COVID-19, or the end of a life-shaping relationship, or the illnesses of loved ones?

The Stoic principle of focusing only on what depends upon us operates here too. Worries carry our minds away into the future. Unless we watch ourselves, we can quickly find ourselves imagining the worst – the death of friends and family, a second great depression, the end of a career …

Marcus Aurelius Distributing Bread To the People, by Joseph-Marie Vien (1765).

Wikimedia Commons

All of these things may come to pass. Or they may not. But, just now, we cannot immediately avert them. What depends on us right now, always, is what we think and do. And there is, for the Stoic, a comfort in this. As Marcus reminds himself:

Do not disturb yourself by thinking of your whole life. Don’t let your thoughts all at once embrace all the various troubles which may … befall you: but on every occasion ask yourself: What is there in this which is intolerable and past bearing? For you will be ashamed to confess. Next, remember that neither the future nor the past pains you, but only the present.

The parallels between this attitude and other spiritual traditions, notably Buddhism, are clear. For Marcus, the inner life of the wise person will be as serene as an open sky, even under fire.

He is content with two things: to accomplish the present action with justice, and to love the fate which has been allotted to him, here and now.

Does this mean then, that we should just accept the worst, rather than struggling to prevent it?

No: we each have a small range of things we can do and influence at any time. We can increase our understanding, start new initiatives, form or join groups, advocate and persuade others to the best of our powers.

But Marcus asks us also to recognise this: however great and urgent the causes we take up, any positive change will always consist of a lot of small decisions, each taken in the present moment.

And each of these decisions is more likely to be efficacious if we can calmly and clearly assess what is possible, rather than giving way to anxiety, fear, hatred or despair.

A soul’s secrets

Unlike much philosophy, the meditations of Marcus are mostly easy to grasp. The philosopher-emperor writes beautifully, with an honesty that can be affecting.

The difficulty lies in really applying these simple, often striking ideas to our lives.

It is (alas) somewhat easier to see why it is right to serenely bear misfortunes and forbear others’ flaws; to remember that “we are made for cooperation, like feet, like hands, like eyelids”; and not to fear death but embrace life in full awareness of one’s mortality, than to do these things in the heat of the moment.

This is why the traditional title, Meditations, is telling.

Marcus Aurelius Distributing Bread To the People, by Joseph-Marie Vien (1765).

Wikimedia Commons

All of these things may come to pass. Or they may not. But, just now, we cannot immediately avert them. What depends on us right now, always, is what we think and do. And there is, for the Stoic, a comfort in this. As Marcus reminds himself:

Do not disturb yourself by thinking of your whole life. Don’t let your thoughts all at once embrace all the various troubles which may … befall you: but on every occasion ask yourself: What is there in this which is intolerable and past bearing? For you will be ashamed to confess. Next, remember that neither the future nor the past pains you, but only the present.

The parallels between this attitude and other spiritual traditions, notably Buddhism, are clear. For Marcus, the inner life of the wise person will be as serene as an open sky, even under fire.

He is content with two things: to accomplish the present action with justice, and to love the fate which has been allotted to him, here and now.

Does this mean then, that we should just accept the worst, rather than struggling to prevent it?

No: we each have a small range of things we can do and influence at any time. We can increase our understanding, start new initiatives, form or join groups, advocate and persuade others to the best of our powers.

But Marcus asks us also to recognise this: however great and urgent the causes we take up, any positive change will always consist of a lot of small decisions, each taken in the present moment.

And each of these decisions is more likely to be efficacious if we can calmly and clearly assess what is possible, rather than giving way to anxiety, fear, hatred or despair.

A soul’s secrets

Unlike much philosophy, the meditations of Marcus are mostly easy to grasp. The philosopher-emperor writes beautifully, with an honesty that can be affecting.

The difficulty lies in really applying these simple, often striking ideas to our lives.

It is (alas) somewhat easier to see why it is right to serenely bear misfortunes and forbear others’ flaws; to remember that “we are made for cooperation, like feet, like hands, like eyelids”; and not to fear death but embrace life in full awareness of one’s mortality, than to do these things in the heat of the moment.

This is why the traditional title, Meditations, is telling.

Roman bust of Marcus Aurelius.

Wikimedia Commons

Readers who go to this classic expecting an ordered, linear philosophical argument will be quickly disillusioned. There are many repetitions and seeming hesitations. Many key Stoic ideas, and Marcus’ own preoccupations (for instance, with how to respond to schemers, and accept his own death) return multiple times. He reformulates his ideas in new ways, striving to find their most compelling expression.

Indeed the Meditations, as scholar Pierre Hadot has argued, need to be seen as an exemplar of a particular Stoic exercise, explicitly prescribed by Epictetus. This involved writing key precepts down as a means to later recall them and to deeply internalise them as philosophical aids to call upon at need.

All this makes the Meditations the singular classic that it is. Or, in Hadot’s moving words:

In world literature one finds lots of preachers, lesson-givers, and censors, who moralise to others with complacency, irony, cynicism, or bitterness; but it is extremely rare to find a person training himself to live and to think like a human being …

We feel “a highly particular emotion”, Hadot continues, as we witness Marcus trying, as we each do, “to live in complete consciousness and lucidity; to give each of our instants its fullest intensity; and to give meaning to our entire life”.

“Marcus is talking to himself”, Hadot observes, “but we get the impression that he is talking to each one of us”.

Roman bust of Marcus Aurelius.

Wikimedia Commons

Readers who go to this classic expecting an ordered, linear philosophical argument will be quickly disillusioned. There are many repetitions and seeming hesitations. Many key Stoic ideas, and Marcus’ own preoccupations (for instance, with how to respond to schemers, and accept his own death) return multiple times. He reformulates his ideas in new ways, striving to find their most compelling expression.

Indeed the Meditations, as scholar Pierre Hadot has argued, need to be seen as an exemplar of a particular Stoic exercise, explicitly prescribed by Epictetus. This involved writing key precepts down as a means to later recall them and to deeply internalise them as philosophical aids to call upon at need.

All this makes the Meditations the singular classic that it is. Or, in Hadot’s moving words:

In world literature one finds lots of preachers, lesson-givers, and censors, who moralise to others with complacency, irony, cynicism, or bitterness; but it is extremely rare to find a person training himself to live and to think like a human being …

We feel “a highly particular emotion”, Hadot continues, as we witness Marcus trying, as we each do, “to live in complete consciousness and lucidity; to give each of our instants its fullest intensity; and to give meaning to our entire life”.

“Marcus is talking to himself”, Hadot observes, “but we get the impression that he is talking to each one of us”.

Authors: Matthew Sharpe, Associate Professor in Philosophy, Deakin University