'Expect sexism': a gender politics expert reads Julia Gillard's Women and Leadership

- Written by Blair Williams, Associate Lecturer, School of Political Science and International Relations, Australian National University

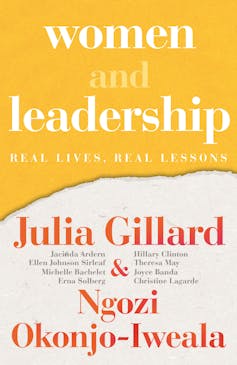

Why are there so few women at the top levels of politics? This question is at the centre of the new book, Women and Leadership, co-authored by Australia’s first woman prime minister, Julia Gillard, and former Nigerian finance minister, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala.

Using their personal experiences and interviews with an impressive group of eight women leaders - including Theresa May, Hillary Clinton, Jacinda Ardern and Christine Lagarde - Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala test various academic studies to see if their findings are reflected in reality.

Penguin Books Australia

Theses studies include media coverage of women’s leadership, as well as perceptions of women’s “power-seeking” and gender norms around leadership.

What results is both a sobering reminder that sexism isn’t going away anytime soon and an empowering message about women’s strength and resilience.

As an academic researching women’s political leadership, this book acts as a crucial point between scholarly studies and public debate. It also offers a fresh perspective of the many issues women in leadership face.

Here are four key messages:

1. The fashion police are everywhere

Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala find women leaders are heavily judged for their appearance. This was a problem faced by all leaders interviewed, despite their diverse experiences and locations.

However, there were still differences across the world. Clinton, a former US presidential candidate and secretary of state, was known for her pant suits - which she said helped her feel professional and “fit in”. But former Liberian president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf noted how she “would have got some eyes as a woman wearing pant suits” and traditional dress worked best for her.

Penguin Books Australia

Theses studies include media coverage of women’s leadership, as well as perceptions of women’s “power-seeking” and gender norms around leadership.

What results is both a sobering reminder that sexism isn’t going away anytime soon and an empowering message about women’s strength and resilience.

As an academic researching women’s political leadership, this book acts as a crucial point between scholarly studies and public debate. It also offers a fresh perspective of the many issues women in leadership face.

Here are four key messages:

1. The fashion police are everywhere

Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala find women leaders are heavily judged for their appearance. This was a problem faced by all leaders interviewed, despite their diverse experiences and locations.

However, there were still differences across the world. Clinton, a former US presidential candidate and secretary of state, was known for her pant suits - which she said helped her feel professional and “fit in”. But former Liberian president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf noted how she “would have got some eyes as a woman wearing pant suits” and traditional dress worked best for her.

Hillary Clinton has said her pantsuits made her feel ‘ready to go’.

David Moir/AAP

There can also be power in clothing. For example, New Zealand’s Ardern was seen to show compassion, empathy and solidarity when she wore a hijab after the Christchurch terrorist attack. As Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala write,

it became a symbol of love in the face of hate. There was a transcendent power in appearance.

2. Prepare to be judged for your reproductive choices

The book also explores how women leaders are judged for their reproductive choices. While fatherhood increases perceptions of male leaders as affable, relatable and conventional, public motherhood is a far more problematic experience.

Read more:

How Julia Gillard forever changed Australian politics - especially for women

As the authors note, women leaders with young children are frequently asked, “who’s minding the kids?”

Seven hours after her election, Ardern was asked on national television about her plans for having children. When she had her daughter, there was intense media scrutiny about how she would juggle her leadership role and her baby. Yet male leaders, such as former UK prime minister Tony Blair, who welcome babies in office, are not questioned about who will be looking after them.

Hillary Clinton has said her pantsuits made her feel ‘ready to go’.

David Moir/AAP

There can also be power in clothing. For example, New Zealand’s Ardern was seen to show compassion, empathy and solidarity when she wore a hijab after the Christchurch terrorist attack. As Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala write,

it became a symbol of love in the face of hate. There was a transcendent power in appearance.

2. Prepare to be judged for your reproductive choices

The book also explores how women leaders are judged for their reproductive choices. While fatherhood increases perceptions of male leaders as affable, relatable and conventional, public motherhood is a far more problematic experience.

Read more:

How Julia Gillard forever changed Australian politics - especially for women

As the authors note, women leaders with young children are frequently asked, “who’s minding the kids?”

Seven hours after her election, Ardern was asked on national television about her plans for having children. When she had her daughter, there was intense media scrutiny about how she would juggle her leadership role and her baby. Yet male leaders, such as former UK prime minister Tony Blair, who welcome babies in office, are not questioned about who will be looking after them.

Jacinda Ardern has taken her daughter Neve to the UN General Assembly.

Carlo Allegri/ AAP

And what about women leaders who don’t have children? Gillard is intrigued by the respectful treatment of former British prime minister May’s childlessness, as she had a polar opposite experience in Australia (who could forget the frenzy sparked by her empty fruit bowl).

Gillard makes a thought-provoking point here about choice. May wanted, but was unable, to have children, while Gillard was deliberately child-free. Perhaps this was the cause of the criticism she faced. As Gillard writes,

in being seen to offend against female stereotypes, is there anything bigger than not becoming a mother by choice?

3. The situation is not getting better

The book makes the point that despite the focus on women in politics, the experience for those at the top is not necessarily improving.

As someone whose research found media reaction to May in 2016 was more gendered than for Margaret Thatcher in 1979, I wasn’t shocked to read this. However, it was still surprising to learn that Michelle Bachelet – Chile’s president from 2006-10 and 2014-18 – noticed things were worse in her second term.

Read more:

Women leaders and coronavirus: look beyond stereotypes to find the secret to their success

Initially assuming the pressure of gendered expectations had improved the second time around, Bachelet realised,

it was the same or worse. I think politics is getting more complicated these days and more vicious. There is less respect. It’s more personalised now.

All leaders interviewed said they were conscious of the difficulties of finding a balance in leadership style. If they were too strong or assertive, they could be seen as “cold”, “robotic” or “bitchy”.

4. ‘Be aware, not beware’

The experiences and advice of these eight high-profile women leaders reveal how sexism is par for the course.

This message is hammered home in the final chapter, in which Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala note “Be aware, not beware”. They argue that they want to inspire women to pursue politics and leadership roles, but glossing over the challenges would be dishonest and insulting.

Jacinda Ardern has taken her daughter Neve to the UN General Assembly.

Carlo Allegri/ AAP

And what about women leaders who don’t have children? Gillard is intrigued by the respectful treatment of former British prime minister May’s childlessness, as she had a polar opposite experience in Australia (who could forget the frenzy sparked by her empty fruit bowl).

Gillard makes a thought-provoking point here about choice. May wanted, but was unable, to have children, while Gillard was deliberately child-free. Perhaps this was the cause of the criticism she faced. As Gillard writes,

in being seen to offend against female stereotypes, is there anything bigger than not becoming a mother by choice?

3. The situation is not getting better

The book makes the point that despite the focus on women in politics, the experience for those at the top is not necessarily improving.

As someone whose research found media reaction to May in 2016 was more gendered than for Margaret Thatcher in 1979, I wasn’t shocked to read this. However, it was still surprising to learn that Michelle Bachelet – Chile’s president from 2006-10 and 2014-18 – noticed things were worse in her second term.

Read more:

Women leaders and coronavirus: look beyond stereotypes to find the secret to their success

Initially assuming the pressure of gendered expectations had improved the second time around, Bachelet realised,

it was the same or worse. I think politics is getting more complicated these days and more vicious. There is less respect. It’s more personalised now.

All leaders interviewed said they were conscious of the difficulties of finding a balance in leadership style. If they were too strong or assertive, they could be seen as “cold”, “robotic” or “bitchy”.

4. ‘Be aware, not beware’

The experiences and advice of these eight high-profile women leaders reveal how sexism is par for the course.

This message is hammered home in the final chapter, in which Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala note “Be aware, not beware”. They argue that they want to inspire women to pursue politics and leadership roles, but glossing over the challenges would be dishonest and insulting.

Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala say women leaders should expect sexist commentary.

Lisi Niesner/AAP

Summarising the insights gleaned from previous chapters, Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala offer some stand-out lessons that will aid aspiring women leaders. These include:

expect sexism and sexist commentary relating to your appearance, family and leadership style and figure out early on how you will respond to this

support other women, whether through network-building, mentoring, role-modelling or general solidarity

persevere.

A reality check

Women and Leadership is, at times, a depressing reality check that feminism still has a long way to go. However, readers should not come away from this feeling hopeless or disheartened.

Rather, they can appreciate the respect the authors have given them by speaking plainly about the realities women leaders face.

Perhaps more consideration could have been given to the experiences of women in less senior positions. Do we need to hear from the success stories when we talk about the struggles of women in leadership, or could we perhaps also learn from those whose glass ceilings were just too thick?

Read more:

Fiction, fact and Hillary Clinton: an American politics expert reads Rodham

While this book might be less useful for women - and men - without leadership aspirations, its general analysis of gender stereotypes and double standards still makes it a worthwhile read.

This is also problem that women cannot fix alone. Men need to do their bit, by calling out sexism and supporting women. The media must also be more active in combating sexism and misogyny.

One enduring message of this book is that progress and equality are not linear.

Sexism doesn’t just one day magically disappear. Rather, it can only be dismantled through constant pressure and the actions of those who persevere.

Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala say women leaders should expect sexist commentary.

Lisi Niesner/AAP

Summarising the insights gleaned from previous chapters, Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala offer some stand-out lessons that will aid aspiring women leaders. These include:

expect sexism and sexist commentary relating to your appearance, family and leadership style and figure out early on how you will respond to this

support other women, whether through network-building, mentoring, role-modelling or general solidarity

persevere.

A reality check

Women and Leadership is, at times, a depressing reality check that feminism still has a long way to go. However, readers should not come away from this feeling hopeless or disheartened.

Rather, they can appreciate the respect the authors have given them by speaking plainly about the realities women leaders face.

Perhaps more consideration could have been given to the experiences of women in less senior positions. Do we need to hear from the success stories when we talk about the struggles of women in leadership, or could we perhaps also learn from those whose glass ceilings were just too thick?

Read more:

Fiction, fact and Hillary Clinton: an American politics expert reads Rodham

While this book might be less useful for women - and men - without leadership aspirations, its general analysis of gender stereotypes and double standards still makes it a worthwhile read.

This is also problem that women cannot fix alone. Men need to do their bit, by calling out sexism and supporting women. The media must also be more active in combating sexism and misogyny.

One enduring message of this book is that progress and equality are not linear.

Sexism doesn’t just one day magically disappear. Rather, it can only be dismantled through constant pressure and the actions of those who persevere.

Authors: Blair Williams, Associate Lecturer, School of Political Science and International Relations, Australian National University