The government would save $1 billion a year with proposed university reforms — but that's not what it's telling us

- Written by Mark Warburton, Honorary Senior Fellow, University of Melbourne

Federal Education Minister Dan Tehan released his Job-ready Graduates Package on June 19 2020. In his National Press Club address, he said it would help drive our economic recovery after COVID-19 and “put more funding into the system in a way that encourages people to study in areas of expected employment growth”.

He said the package would deliver an additional 39,000 university places by 2023 and 100,000 places by 2030.

But my analysis shows the growth in student places is illusory. It will not meet any additional demand from the COVID-19-induced economic slowdown or future growth in the university-age cohort.

I show that — over the period from December 2017 (when the government put a cap on demand-driven funding) to 2024 (when the job-ready policies are fully implemented) — the government will deliver itself an annual saving of nearly A$1 billion.

A bit of background

In 2018, the government used a legislative handbrake to stop student subsidies for bachelor degrees from growing by capping funding.

Before that, the government was providing funding to universities based on how many students had enrolled. A two-year freeze on funding was followed by population-based increases of less than the inflation rate.

This stopped new student places being subsidised. And over time, it eroded the number of places receiving a subsidy.

There was no coherent plan for longer-term growth. The Job-ready policies are meant to fix this. If legislation passes, they will start in 2021 and be fully phased in by 2024.

New subsidy and student contribution arrangements would replace the current arrangements. The total revenue for a student place would be better aligned with the estimated cost of teaching in each discipline, removing the surplus funding now spent on other things like research.

Student contributions are being set to encourage them to study things like maths and agriculture, and to discourage them from studying things like history and communications. The government subsidy meets the remainder of the cost in each discipline.

These changes save the government money, but it spends some of it on “additional student places”. It also spends some on grants to promote links with industry and on resuming inflation-linked increases of the subsidies for student places.

Read more: Coronavirus and university reforms put at risk Australia's research gains of the last 15 years

It is a complicated package. There is a three-year transition period in which existing students, whose contributions would otherwise increase, stay on the old funding arrangements.

If a university would get more funding for the same total number of students under the old funding arrangements, the government will make up the difference. Funding will be progressively increased to allow universities to provide more places over this three-year period.

The government didn’t release any analysis of the end point of its changes. What will have happened to university funding by 2024? Will there be more student places than when it first capped the system? Will it be spending more or less than in the past?

My calculations

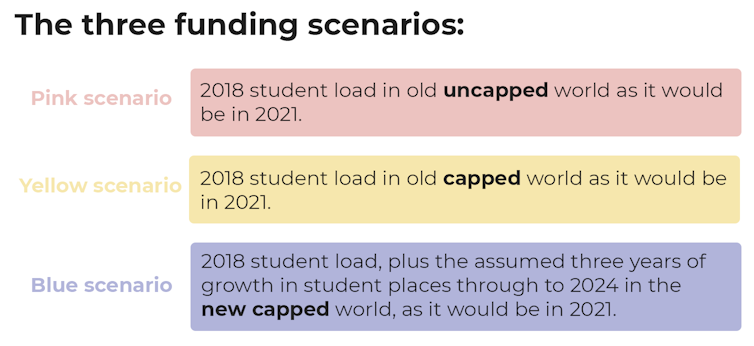

In the pink scenario (below), I calculate funding for 2018 student load using current 2021 funding rates and no funding cap.

In the yellow scenario, I calculate funding for 2018 student load using current 2021 funding rates and with the funding cap in place at its 2021 value. I calculate how many places are no longer funded due to the operation of the cap using the average funding rate for all places.

In the blue scenario, I calculate how much the 2018 student load, combined with the growth in student places to 2024, would be worth in 2021 (in 2021 dollars) with the new Job-ready graduate funding rates.

The Conversation/Author provided, CC BY-ND

Comparing the pink and yellow scenarios

From 2018 to 2021, the funding cap has reduced university revenue by around $266 million, down to $12.6 billion. Using the average bachelor subsidy rate, around 23,000 student places are no longer subsidised.

Comparing the yellow and blue scenarios

University revenue declines by a further $0.5 billion to $12.1 billion. To earn this revenue, universities will have to provide around 11,700 more student places than in the yellow scenario.

Those 11,700 extra places arise from the Job-ready policy providing 3.5% growth for bachelor degrees at regional campuses, 2.5% for high-growth metropolitan campuses and 1% for low-growth metropolitan campuses.

The government is allocating other places to universities too (for national priorities, the University of Notre Dame Australia and Charles Sturt University’s medical school), but the total number of “new” places remains just over 15,000 – fewer than the 23,000 that have their funding taken away by the operation of the funding cap from 2018 to 2021.

Read more:

The government is making ‘job-ready’ degrees cheaper for students – but cutting funding to the same courses

While universities lose around $0.5 billion in student place funding, they receive an extra $222 million as Industry Linkage funding. We are yet to find out what they need to do for that funding.

The government makes large savings from two sources – students and universities. On average it increases contributions from students and every extra student dollar reduces what the government pays. It also reduces funding overall to more closely align with discipline teaching costs. My model estimates it goes to 94% of its former value.

Total student contributions rise by around $564 million a year in the change from current to new Job-ready graduate rates. Students will pay an average of 48-49% of costs by 2024.

The bottom line

Over the period from December 2017 to 2024, the government will deliver itself an annual saving of around $988 million. Around $266 million is from capping the system over the four years 2018 to 2021. Around $722 million is from the Job-ready policies.

Student choices will be little affected by changing student contribution levels, due to our income-contingent loan system, but restoring indexation of student subsidies is sensible policy. The lack of growth in student places into the future is not. It is essentially a policy to reduce higher education attainment levels.

The Conversation/Author provided, CC BY-ND

Comparing the pink and yellow scenarios

From 2018 to 2021, the funding cap has reduced university revenue by around $266 million, down to $12.6 billion. Using the average bachelor subsidy rate, around 23,000 student places are no longer subsidised.

Comparing the yellow and blue scenarios

University revenue declines by a further $0.5 billion to $12.1 billion. To earn this revenue, universities will have to provide around 11,700 more student places than in the yellow scenario.

Those 11,700 extra places arise from the Job-ready policy providing 3.5% growth for bachelor degrees at regional campuses, 2.5% for high-growth metropolitan campuses and 1% for low-growth metropolitan campuses.

The government is allocating other places to universities too (for national priorities, the University of Notre Dame Australia and Charles Sturt University’s medical school), but the total number of “new” places remains just over 15,000 – fewer than the 23,000 that have their funding taken away by the operation of the funding cap from 2018 to 2021.

Read more:

The government is making ‘job-ready’ degrees cheaper for students – but cutting funding to the same courses

While universities lose around $0.5 billion in student place funding, they receive an extra $222 million as Industry Linkage funding. We are yet to find out what they need to do for that funding.

The government makes large savings from two sources – students and universities. On average it increases contributions from students and every extra student dollar reduces what the government pays. It also reduces funding overall to more closely align with discipline teaching costs. My model estimates it goes to 94% of its former value.

Total student contributions rise by around $564 million a year in the change from current to new Job-ready graduate rates. Students will pay an average of 48-49% of costs by 2024.

The bottom line

Over the period from December 2017 to 2024, the government will deliver itself an annual saving of around $988 million. Around $266 million is from capping the system over the four years 2018 to 2021. Around $722 million is from the Job-ready policies.

Student choices will be little affected by changing student contribution levels, due to our income-contingent loan system, but restoring indexation of student subsidies is sensible policy. The lack of growth in student places into the future is not. It is essentially a policy to reduce higher education attainment levels.

Authors: Mark Warburton, Honorary Senior Fellow, University of Melbourne