Heat-detecting drones are a cheaper, more efficient way to find koalas

- Written by Ryan R. Witt, Conjoint Lecturer | School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle

This article is a preview from Flora, Fauna, Fire, a multimedia project launching on Monday July 13. The project tracks the recovery of Australia’s native plants and animals after last summer’s bushfire tragedy. Sign up to The Conversation’s newsletter for updates.

Last summer’s catastrophic bushfires burnt about one quarter of New South Wales’ best koala habitat. On the state’s mid-north coast, an estimated 30% of koalas were killed.

Collecting the most accurate possible information about surviving koala populations, in both burnt and unburnt areas, will help save these precious few.

But at the moment, accurate information can be hard to come by. A NSW parliamentary inquiry into koala populations last week found that the fires, and general population decline, meant the current estimate of 36,000 koalas in the state was “outdated and unreliable”.

The report warned that without government intervention, wild koalas in NSW were on track for extinction by 2050. It recommended exploring the use of drones, among other detection methods, next fire season.

For the last year, we’ve been developing the use of heat-detecting drones to find koalas at night. This efficient method will save on costs. It will also help better assess koala numbers – a key step in saving the species.

Accurate koala counts are key to successful conservation efforts.

IFAW

Accurate koala counts are key to successful conservation efforts.

IFAW

Promising results

Koalas camouflage well and are notoriously difficult to detect. Traditional methods such as scat surveys or spotlighting with head torches are often considered either too localised, or too labour intensive and costly to efficiently locate and count koalas.

We tested our new koala-locating technique in Port Stephens, NSW, in the winter of 2019. Fortunately, the bush we visited did not burn in the later summer fires. Our method, to be published as a study in the journal Australian Mammalogy, was more efficient and cost effective than traditional koala population survey techniques.

Read more: Scientists find burnt, starving koalas weeks after the bushfires

How much more efficient? Well, by searching forests at night on foot with spotlights we found, on average, about one koala every seven hours.

Flying the thermal drone at night in the same forests, we found an average of one koala every two hours. And this was in an area with a notoriously dispersed population.

This method could potentially be used to assess koala populations in fire-burnt areas over winter this year.

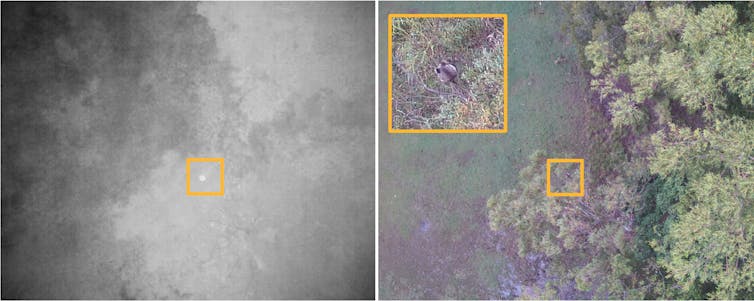

Koala night-time detection and daylight verification. On average, a koala is 17.1% brighter than the surrounding canopy.

A. Roff/NSW DPIE

Koala night-time detection and daylight verification. On average, a koala is 17.1% brighter than the surrounding canopy.

A. Roff/NSW DPIE

Drones have big potential

Victorian authorities used drones during the 2020 summer fires - while fires were still active - to assess the damage in remote areas. Scientists also used drones to help detection dogs find starving koalas in the weeks after fire.

Our work takes the use of drones further, by detecting koala heat signatures at night.

On several occasions we flew the drone back to a possible koala detection at first light and confirmed the thermal signatures were indeed koalas.

Read more: Koalas are the face of Australian tourism. What now after the fires?

We travelled to potential koala habitat in the Port Stephens area. Using a drone with a thermal and a colour camera, we flew a lawnmower pattern (meaning back and forth, so no spots are missed) about 70 metres above the ground. We then checked the results in real-time on a handheld tablet.

We flew the drones mostly at night, as initial surveys suggested koalas were more likely to be detected in the early morning before sunrise. Each flight was around 22 minutes long and simultaneously captured thermal and colour video recordings.

During and immediately after each flight, we checked the footage for signs of koalas. If we saw a large infrared “blob” in the tree canopy, we paused the drone to capture GPS data and detailed images.

Real-life checks

To make sure these “blobs” really were koalas, we needed to lay eyes on the animals. We did this at first light in two ways: one, by physically walking to the suspected koala location to check with binoculars and two, by programming the drone to fly back over the potential koala detection during the day.

This allowed us to simultaneously collect thermal and very high-resolution colour images. It also meant we could verify night-time detections, even in difficult to reach places.

We learnt that koalas noticed the drone approaching but were not bothered by it.

The drone also detected wallabies, possums, grey-headed flying foxes and a number of birds, highlighting the future potential applications of the technology.

Our team comprised experts from the University of Newcastle and the NSW Environment, Energy and Science Group of the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment. We were helped by several local government and not-for-profit groups such as Port Stephens Koalas, Tilligerry Habitat and FAUNA Research Alliance.

On ground observers sight drone detected koalas and identify tree species.

A. Roff/NSW DPIE

On ground observers sight drone detected koalas and identify tree species.

A. Roff/NSW DPIE

How could this help in future?

Under climate change, increasingly frequent and severe fires are likely to drive animal population declines.

A thermal camera won’t be much help in a recently burned area that’s still hot. But our technique could be used to monitor fire-affected bushland in the weeks, months and years following bushfire - even in isolated refuges or difficult terrain.

Heat-detecting drones can help koalas after future fire seasons.

Ben Beaden/AAP

Heat-detecting drones can help koalas after future fire seasons.

Ben Beaden/AAP

In future fire seasons, our method may also be useful for wildlife rescue, localised population monitoring, pre-land use surveys (such as before development, logging or hazard reduction burning), and after rehabilitation to check on released koalas.

Australia has an opportunity to lead the innovative use of emerging technologies such as drones to help find koalas and other hard-to-detect wildlife.

Other species that can be monitored using drones include bears, monkeys, sharks, whales, green sea turtles and albatrosses.

We plan to continue this work in the winter of 2020 in fire-affected areas of NSW to help understand and conserve koala populations.

Read more: Stopping koala extinction is agonisingly simple. But here's why I'm not optimistic

Authors: Ryan R. Witt, Conjoint Lecturer | School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle