Blackout Tuesday: the black square is a symbol of online activism for non-activists

- Written by Jolynna Sinanan, Research Fellow in Digital Media and Ethnography, University of Sydney

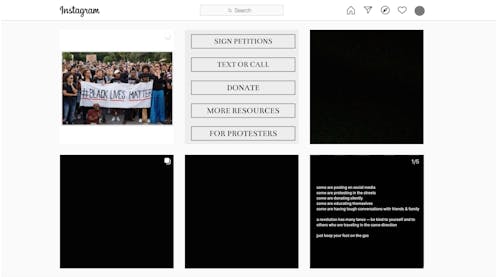

Earlier this week, you might have seen your social media taken over by a stream of posts showing simple images of a black square. These posts, often tagged with #BlackoutTuesday, were gestures of solidarity with protests against the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

There have been more than 28 million of these posts on Instagram, and online services such as Spotify and Apple Music also joined the movement. Social media activism is nothing new, but the scale of #BlackoutTuesday showed not only the cause but also the method of the protest were distinctly 2020.

Read more: The fury in US cities is rooted in a long history of racist policing, violence and inequality

What was Blackout Tuesday?

Last weekend, two black women working in the music industry began a campaign asking the music industry, which they note “has profited predominantly from Black art”, to put its activities on hold for a day on Tuesday June 2.

Using the hashtag #theshowmustbepaused, they began making their case by posting an image to Instagram of a black background and white text asking the music industry to pause and reflect on the ways it disenfranchises black employees.

The movement soon took off: as the week began, posts showing simple black squares quickly proliferated across social media. The hashtags varied, from the original #theshowmustbepaused to #blacklivesmatter and #blackouttuesday.

Strange effects of the black squares

The black square posts have come in many forms. Some show the square alone with no text, some with #BlackoutTuesday and others with #BlackLivesMatter, associating the trend with the established political movement.

Many captions and comments posted with the image express the poster’s desire to educate themselves and others about racial inequality, to stand in solidarity with the wider Black Lives Matter movement, or simply “to do better”.

While the trend gathered momentum with posts from US celebrities as well as ordinary people around the world, it also attracted criticism.

Criticisms include the use of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, which activists use to stay informed about demonstrations, for financial donations and to document racial violence by police. Filling the hashtag’s feed with black squares, some argued, obscured more direct activities associated with the movement, redirected attention and “silenced” activists.

The current situation

Despite the backlash, the sheer numbers of people around the world who have posted black squares indicates that #BlackoutTuesday is a form of political expression that has resonated with the particular moment of June 2020.

Several countries are just coming out of pandemic lockdowns that have lasted for weeks or months. These lockdowns have meant work, education, entertainment and political engagement have largely been experienced online.

Read more: The coronavirus pandemic is boosting the big tech transformation to warp speed

The pandemic and the economic devastation in its wake have left millions of people feeling uncertain and helpless. And in this dismal environment, in the same week the US surpassed 100,000 COVID-19 deaths, George Floyd was killed by police like many other African-American men before him.

Why not everyone is an activist

From the Arab Spring uprisings of the early 2010s to the Hong Kong demonstrations of 2019-20, social media has become an essential tool for political action. Activists use it to organise demonstrations, generate debate and facilitate social change.

However, for many people outside Western, liberal democracies, and in the “Global South”, visible political engagement can have severe consequences. This is particularly true for those who are kept from freedoms and opportunities by systemic exclusion based on race, class, gender or sexuality.

These consequences range from professional or social exclusion to harassment and intimidation to outright persecution and detention. As a result, many people in such societies may subscribe to “non-activism”.

Non-activism means explicitly rejecting visible involvement with political causes to focus on everyday concerns. People may reject activism even while they know doing so makes social change less likely.

Activism for non-activists

Blackout Tuesday was in some ways an ideal form of activism for non-activists, which may explain some of its enormous international popularity.

My own analysis of posts indicates users are based in countries including Ukraine, Brazil, and the Caribbean islands. Those who posted used visual social media to connect the experiences of one individual to structural violence and race-based exclusion that is pervasive in countries beyond the US.

The black square allowed millions of people to engage with a politically charged issue without having to seem too political themselves.

For many, especially those who would not consider themselves “political”, symbolism is a legitimate form of political engagement.

Worlds colliding

Algorithms, applications and automated systems play a significant role in what we see in online media. They affect how content reaches some audiences and not others, and automated systems may also perpetuate racial bias.

When activists turn to social media to further their cause, they too are ruled by the algorithms. We saw this in the criticisms of #BlackoutTuesday posts on Instagram, and particularly those using the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, for preventing the hashtags (and the algorithms) from doing what protest organisers wanted them to do.

We may think of “social media users” as collective audiences, but they are made up of individuals embedded in a variety of contexts who do not necessarily have much in common.

For seasoned activists, #BlackoutTuesday was a moment in which popular support paradoxically made it harder to keep people informed. But for many others, it may have been a step towards political engagement through difficult terrain.

Authors: Jolynna Sinanan, Research Fellow in Digital Media and Ethnography, University of Sydney