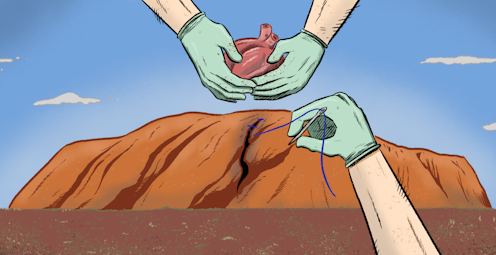

Three years on from Uluru, we must lift the blindfolds of liberalism to make progress

- Written by Stan Grant, Vice Chancellors Chair Australian/Indigenous Belonging, Charles Sturt University

The Uluru Statement from the Heart offered a new compact with all Australians that would reset our national identity and enhance our political legitimacy. But its poetic vision and pragmatism proved its death knell.

Trying to reconcile two historically divergent if not hostile ideas – Indigenous sovereignty and the sovereignty of the Commonwealth – asked the nation to embark on a project of rehabilitation: “Voice, Treaty, Truth”.

Read more: Listening with 'our ears and our eyes': Ken Wyatt's big promises on Indigenous affairs

The proposed constitutionally enshrined Voice to Parliament was rejected; treaty remains a dream, and the Australian people appear generally indifferent to historical introspection.

The Uluru Statement offered nation-building for a nation that seems content with itself.

It was an easy target for conservative politicians.

The great lie of the Turnbull government – that the Voice would be a “third chamber” of parliament – prevailed over Indigenous truth because to enough ears it sounded right.

The appearance of Indigenous people enjoying rights not shared by other Australians was cast as offensive to liberal principles. Indigenous advocates had no simple answer to the bumper-sticker slogan that they were putting race in the constitution.

They were left to try to convince Australians with complicated, long-winded arguments about the scientific fiction of race. The Voice would not be a veto; the “truth” would set us free.

The Uluru Statement was junked and Australians, hitherto generous to the idea of constitutional recognition, barely raised a whimper.

What should have been a high watermark of Australian liberalism became instead a victim of Australian liberalism.

It poses an existential question: can liberal democracy meet the demands of First Nations people?

For classical liberals the answer is no, if it means privileging group rights over the individual.

Some Indigenous people reject liberalism itself as an inherently and irredeemably racist colonial project.

They adopt an ethical stance of “refusal”, citing Canadian First Nations scholar Glen Coulthard, who argues that the liberal form of political recognition reproduces:

the very configurations of colonialist, racist, patriarchal, state power that Indigenous people […] have historically sought to transcend.

Indigenous liberals are in a bind: caught between other Indigenous people who share their struggle and liberals with whom they seek to find common cause.

Can we untie this Gordian knot? Political philosopher Duncan Ivison believes so.

The Uluru Statement, he argues, presented an opportunity for “a refounding of Australia”.

It was an invitation to re-imagine Australian liberalism around what the profoundly influential American political thinker John Rawls called “reasonable pluralism”.

Can a liberal state negotiate unavoidable deep moral and political disagreements without fracturing civic unity?

Take the issues of rights and history: the Scylla and Charybdis of Australian politics.

Navigating the straits between them is treacherous, invariably triggering culture wars over who owns the truth.

Ivison says if Indigenous people are to accept the legitimacy of the state, then the most important shift liberalism can make is to “embrace a more historically informed approach to justice”.

Yet liberalism is a progressive idea that seeks to transcend history.

Political scientist Francis Fukuyama went as far as to declare the Cold War triumph of liberal democracy over Soviet communism the “end of history”.

There is a persuasive imperative of “forgetting”: to “move on” to build a peacefully reconciled nation, free of historical grudges.

Australians may be interested in learning more about our past, but that stops short of national catharsis.

Australians generally don’t think history is a debt to be repaid. Liberalism looks forward, not back.

Symbolic acts of reconciliation – the Stolen Generations apology – are okay, but separate rights not so much.

Any full consideration of rights is beyond this article, cutting across issues like recognition, identity and political power.

The pertinent tension here is between group rights or individual rights.

Ivison concedes it is a tight fit.

It is not beyond the scope of liberal democracies to embrace group rights.

Ivison’s native Canada incorporates what’s been called “a doctrine of Aboriginal rights”: not so Australia.

Even Native Title – a group right – was a legislative response to rein in the scope of the historic Mabo High Court decision amid concerns among pastoralists and miners, and a scare campaign that Australians could lose their backyards.

Indigenous rights challenge the Australian identity as egalitarian, multicultural, and tolerant: the fair go does not mean a better go.

Australians can support assimilationist projects of equality as they did overwhelmingly in the 1967 referendum when they were told Aborigines “want to be Australians too”.

However, mischievous politicians miscast the Indigenous Constitutional Voice as quasi-separatism. The inference was it was not just illiberal, but un-Australian.

To change Australia, Australians must want to change.

Consistent polling shows healthy support for the concept of constitutional recognition, but history reminds us how goodwill can dissolve against a fear campaign.

Ivison and other like-minded liberals make a heroic attempt to renovate Australian liberalism, but the people seem content with the liberalism they have.

To paraphrase Bertolt Brecht: what do you want to do, elect a new people?

Like Ivison, I believe liberalism is an idea worth preserving.

The Uluru Statement was a clarion call for all Australians to walk together for a better future.

To find our way, we may first have to lift some of the blindfolds of our liberalism.

Authors: Stan Grant, Vice Chancellors Chair Australian/Indigenous Belonging, Charles Sturt University