Captain Cook wanted to introduce British justice to Indigenous people. Instead, he became increasingly cruel and violent

- Written by Shino Konishi, ARC Research Fellow, University of Western Australia

Captain James Cook arrived in the Pacific 250 years ago, triggering British colonisation of the region. We’re asking researchers to reflect on what happened and how it shapes us today. You can see other stories in the series here and an interactive here.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

In The Apotheosis of Captain Cook, anthropologist Gananath Obeyesekere describes James Cook as a Kurtz-like figure, inspired by Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness.

He suggests Cook initially saw himself as an enlightened “civiliser”, bringing a new vision of the world to the so-called “savage lands” of the South Seas.

But over the course of his three voyages, Cook instead came to embody the “savagery” he ostensibly despised, indulging in increasingly tyrannical, punitive and violent treatment of Indigenous people in the Pacific.

Cook’s evolution was triggered by Indigenous people’s seeming refusal to embrace the gift of civilisation he offered, such as livestock and garden beds sown with Western crops and a justice system modelled after Britain’s.

After revisiting Tahiti on his third voyage, he was dismayed to discover that despite a decade of European encounters and exchanges, he nonetheless found

neither new arts nor improvements in the old, nor have they copied after us in any one thing.

He became increasingly frustrated by their determination to maintain their own laws and manners, especially their tendency to “steal”.

‘Hints’ for fostering good relations

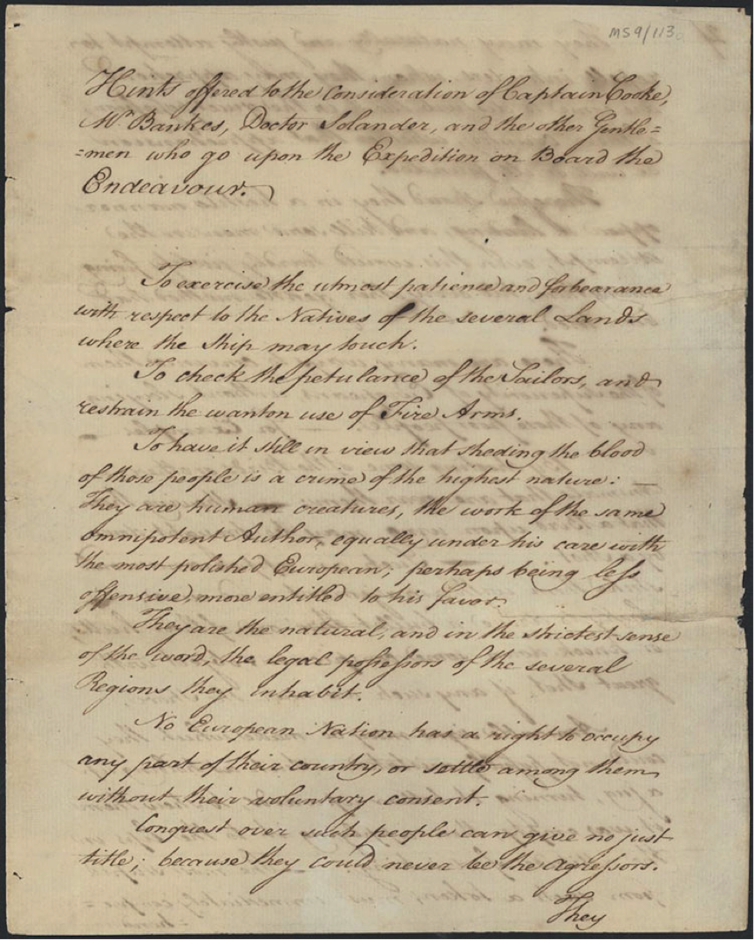

For his first expedition on the Endeavour, Cook received a document called Hints prepared by the Earl of Morton, president of the Royal Society, providing advice on how to deal with Indigenous people.

The earl reminded Cook’s crew that Indigenous peoples were the “legal possessors of the several regions they inhabit” and

No European Nation has the right to occupy any part of their country … without their voluntary consent.

He also advised Cook and his naturalists to:

Exercise the utmost patience and forbearance with respect to the Natives of the several lands where the ship may touch. To check the petulance of the Sailors and restrain the wanton use of Fire Arms. To have it still in view that shedding the blood of these people is a crime of the highest nature.

Cook decided the best way to prevent violence and foster good relations with Indigenous people he encountered was to demonstrate the “superiority” of European weapons, assuming

once they are sensible of these things, a regard for their own safety will deter them from disturbing you.

A passage from Hints.

National Library of Australia, Papers of Sir Joseph Banks

A passage from Hints.

National Library of Australia, Papers of Sir Joseph Banks

Cook’s early attempts to promote British justice

Cook was determined, however, to follow Morton’s instructions to the letter and ensure his crew, under threat of punishment, treated Indigenous people respectfully.

He enforced this rule in April 1769 during their first sojourn in Tahiti, when the ship’s butcher threatened to slit the throat of the high chief Te Pau’s wife when she refused to exchange her hatchet for a nail.

Outraged, Te Pau told the botanist Joseph Banks, with whom he had developed a close relationship. Cook then ordered the butcher to be publicly flogged in front of the Tahitians so they could witness British justice.

Yet, instead of being satisfied, the Tahitians were appalled to witness this form of corporal punishment.

A few days later, Cook’s resolve to maintain peaceful relations was tested again when their quadrant was stolen from a guarded tent. This scientific instrument was essential for observing the transit of Venus, a central aim of the expedition.

According to Cook’s journal, his first response was to “seize upon Tootaha” [Tutaha], the chief of Papara in western Tahiti, or

some others of the Principle people and keep them in custody until the Quadt was produce’d.

But he soon realised this would alarm the Tahitians. After realising Tutaha played no role in the theft, Cook ordered his men not to seize him. And Banks, tipped off by Te Pau as to the quadrant’s whereabouts, soon retrieved it.

On these occasions, Cook attempted to demonstrate what he saw as the fairness of British law to the Tahitians.

Johann Reinhold Forster, naturalist on Cook’s second voyage, also suggested Cook’s reactions were tempered by the presence of the naturalists, who were not subject to his authority.

A change in temperament

By his third voyage on the Resolution and Discovery from 1776-80, however, Cook would no longer be so measured in his treatment of Indigenous people.

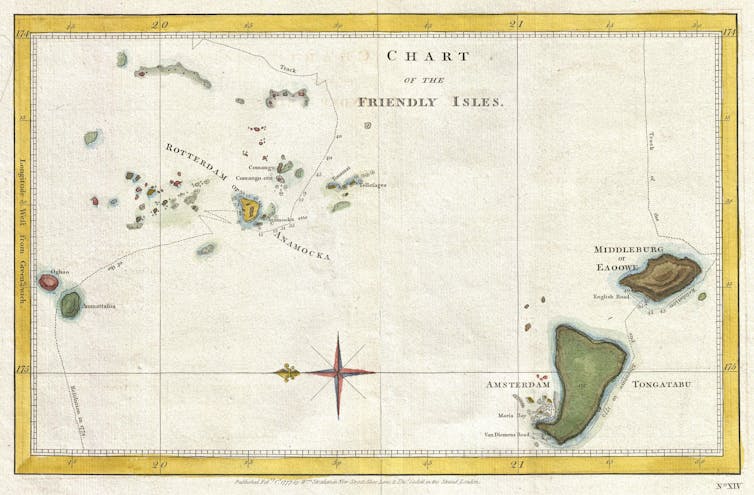

This was evident during his almost three-month stay in Tonga, then known as the Friendly Islands.

Chart of the Friendly Isles, published in 1777.

Wikimedia Commons

Chart of the Friendly Isles, published in 1777.

Wikimedia Commons

In May 1777, Cook visited Nomuka, and after exchanging gifts with the leading chief, Tupoulangi, he set up a market where the British received great stores of fresh meat and fruit.

Despite the efforts of both Cook and Tupoulangi to ensure order in the market, however, thefts still occurred.

On one occasion, an islander was caught trying to steal a small winch used to make rope, and Cook “ordered him a dozen lashes”. After the man was “severely flogg’d”, his hands were tied behind his back and he was carried to the market where he was

not releas’d till a large hog was brought for his ransom.

William Anderson, a surgeon on the expedition, thought the lashes were a justifiable punishment and deterrent. However, he said what came after would

not be found consonant with the principles of justice or humanity.

Cook later complained the chiefs were ordering their servants to steal from the market and “floging [sic] made no more impression” on them since the chiefs would “often advise us to kill them”.

Reluctant to resort to execution for stealing, Cook’s crew soon found an alternative method of punishment: shaving the heads of offenders. This, he said,

was looked upon as a mark of infamy.

A month later, the expedition moved to the island Tongatapu. Here, there was a radical shift in Cook’s conduct. As anthropologist Anne Salmond described it, he was “guilty of great cruelty” even in the eyes of his own men.

Historian John Beaglehole believes Cook was “at his wits’ end” by the thievery at Tongatapu and responded by applying “the lash as he had never done before”.

Instead of shaving the heads of thieves, Cook again ordered them to be severely flogged and ransomed.

Cut-throat retribution

The Discovery’s master, Thomas Edgar, kept a tally of these punishments and noted that in a two-week span, eight men were punished with 24-72 lashes apiece for stealing items such as a “tumbler and two wine glasses”.

Cook even punished his own men with the maximum 12 lashes for “neglect of duty” when thefts happened on their watch.

He also resorted to punishments which midshipman George Gilbert deemed “unbecoming of a European”, including:

cutting off their ears; fireing at them with small shot; or ball as they were swimming or paddling to the shore; and suffering the people (as he rowed after them) to beat them with the oars; and stick the boat hook into them; wherever he could hit them

Edgar described how one Tongan prisoner who received 72 lashes and then was dealt “a strange punishment” by

scoring both his Arms with a common Knife by one of our Seamen Longitudinally and transversly [sic], into the Bone.

This horrific and excessive carving of crosses into the man’s shoulders is most reminiscent of Kurtz in Heart of Darkness.

Blind hypocrisy

Cook’s increasingly violent punishments reflected his sheer frustration over the refusal of Indigenous people to recognise the superiority of Western ways and Europeans’ concepts of property.

Of course, while they were very protective and jealous of their own possessions, Cook and his crew were blind to any Indigenous concepts of property.

As he journeyed through the Pacific, Cook, like other European voyagers, freely collected water and fruit, netted fish and turtles, hunted birds and game and cut down trees for wood, never thinking Indigenous people would regard these valuable resources as their property nor construe such actions as theft.

When the expedition reached Endeavour River, near present-day Cooktown in far-north Queensland, the Guugu Yimithirr people tried to reclaim turtles Cook’s men had fished from their waters. They were rebuffed by Cook’s men and angrily set fires in retaliation.

Cook, however, did not recognise this as punishment or retribution for the stolen turtles. Instead he thought their actions were “troublesome”, so was

obliged to fire a musquet load[ed] with small short at some of the ri[n]g leaders.

Throughout his voyages, Cook faithfully followed the Earl of Morton’s advice to show off the superiority of European might, but he increasingly failed “to check” his own “petulance” and “restrain the wanton use of Fire Arms”.

Most, significantly, through his administering of rough justice against Indigenous people for apparent thieving, Cook forgot Morton’s edict that

shedding the blood of these people is a crime of the highest nature.

Authors: Shino Konishi, ARC Research Fellow, University of Western Australia