1 in 10 children affected by bushfires is Indigenous. We've been ignoring them for too long

- Written by Bhiamie Williamson, Research Associate & PhD Candidate, Australian National University

The catastrophic bushfire season is officially over, but governments, agencies and communities have failed to recognise the specific and disproportionate impact the fires have had on Aboriginal peoples.

Addressing this in bushfire response and recovery is part of Unfinished Business: the work needed for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to meet on more just terms.

In our recent study, we found more than one quarter of the Indigenous population in New South Wales and Victoria live in a fire-affected area. That’s more than 84,000 people. What’s more, one in ten infants and children affected by the fires is Indigenous.

Read more: Strength from perpetual grief: how Aboriginal people experience the bushfire crisis

But in past bushfire inquires and royal commissions, Aboriginal people have been mentioned only sparingly. When referenced now, it’s only in relation to cultural burning or cultural heritage. This must change.

Bushfire residents

Indigenous people comprise only 2.3% of the total population of NSW and Victoria. But they make up nearly 5.4% of the 1.55 million people living in fire-affected areas of these states.

And of the total Indigenous population in fire-affected areas, 36% are less than 15 years old. This is a major concern for delivering health services and education after bushfires have struck.

Importantly, where Indigenous people live has a marked spatial pattern.

There are 22 discrete Aboriginal communities in rural fire-affected areas. Of these, 20 are in NSW, often former mission lands where people were forcibly moved or camps established by Aboriginal peoples.

Ten per cent of Indigenous people in fire-affected areas in NSW and Victoria live in these communities.

And those living in larger towns and urban areas aren’t evenly distributed. For example, Indigenous people comprise 10.6% of residents in fire-affected Nowra–Bomaderry, compared with 1.9% of residents in fire-affected Bowral–Mittagong.

These statistics are steeped in histories and geographies that need to directly inform where and how services are delivered.

Indigenous rights and interests

Aboriginal people hold significant legal rights and interests over lands and waters in the fire-affected areas. These are recognised by state, federal or common law. This includes native title, land acquired through the NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act or lands covered by Registered Aboriginal Parties in Victoria.

Even where there’s no formal recognition, all fire-affected lands have Aboriginal ownership held and passed down through songlines, languages and kinship networks.

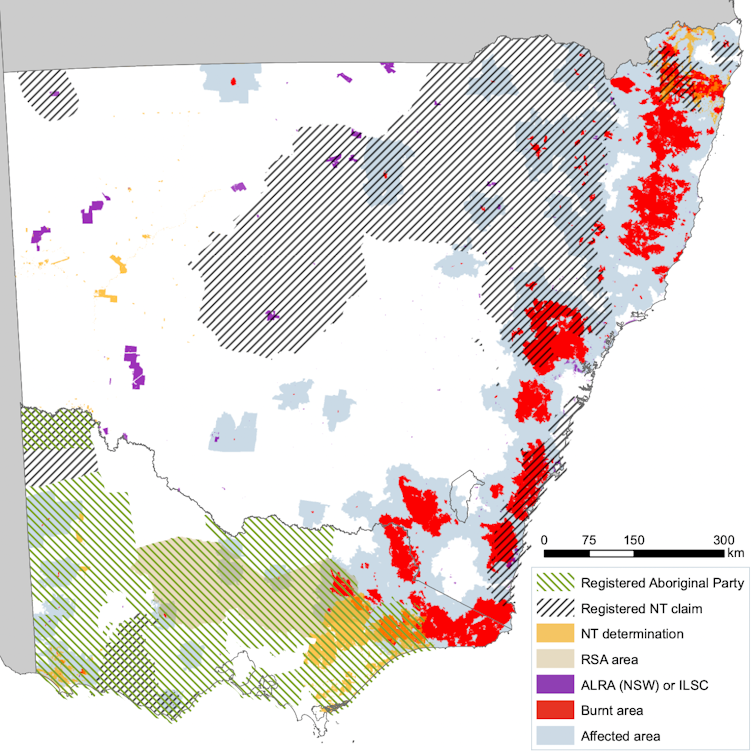

Areas in NSW and Victoria burnt and affected by fires of 250 ha or more, July 1, 2019 to January 23, 2020, and Aboriginal legal interests in land.

Author provided

Areas in NSW and Victoria burnt and affected by fires of 250 ha or more, July 1, 2019 to January 23, 2020, and Aboriginal legal interests in land.

Author provided

The nature of these legal rights and interests means the bushfires have different consequences for Aboriginal rights-holders than for non-Indigenous landowners.

Many non-Indigenous land-owners in the fire-affected areas face the difficult decision of whether to stay and rebuild, or sell and move on. Traditional owners, on the other hand, are in a far more complex and unending situation.

Traditional owners carry inter-generational responsibilities, practices and more that have been formed with the places the know as their Country.

They can leave and live on someone else’s Country, but their Country and any formally recognised communal land and water rights remain in the fire-affected area.

Relegated to the past

Clearly, Aboriginal people have unique experiences with bushfire disasters, but Aboriginal voices have seldom been heard in the recovery processes that follow.

Read more: Our land is burning, and western science does not have all the answers

The McLeod Inquiry, which followed the 2003 Canberra bushfires and the 2009 Black Saturday Royal Commission – were critical processes of reflection and recovery for the nation. Even in these landmark reports, references to Aboriginal people are almost completely absent.

There were only four brief mentions across three volumes of the Black Saturday Royal Commission. Two were cultural heritage protections discussions in relation to pre-bushfire season preparation, and two were historical references to past burning practices.

In other words, Aboriginal people – their cultural practices, ways of life and land management techniques – are relegated to the past.

This approach must change to acknowledge that Aboriginal people are present in contemporary society, and have distinct experiences with bushfire disasters.

More than cultural burning

This year, we’ve seen strong interest in Aboriginal people’s fire management, including in the early months of the federal royal commission, and in NSW and Victoria state inquiries.

Aboriginal voices only in regards to cultural burning is deeply problematic.

Shutterstock

Aboriginal voices only in regards to cultural burning is deeply problematic.

Shutterstock

But including Aboriginal voices only in regards to cultural burning is deeply problematic. Yet, it’s an emerging trend – not only in these official responses, but in the media.

This narrowly defined scope precludes the suite of concerns Aboriginal people bring to bushfire risk matters. Their concerns go across the natural hazard sector’s spectrum of preparation, planning, response and recovery.

Aboriginal people need to be part of the broad conversation that bushfire decision-makers, researchers, and the public sector are having.

Amplifying Aboriginal voices

To date, Victoria offers the most substantial effort to include Aboriginal voices by establishing an Aboriginal reference group to work alongside the bushfire recovery agency. But Aboriginal people require a much stronger presence in every facet of these state and national inquiries.

We identify three foundational steps:

acknowledge that Aboriginal people have been erased, made absent and marginalised in previous bushfire recovery efforts, and identify and address why this continues to happen

establish non-negotiable instructions for including Aboriginal people in the terms of reference and membership of post-bushfire inquiries

establish Aboriginal representation on relevant government committees involved in decision-making, planning and implementation of disaster risk management.

Read more: Friday essay: this grandmother tree connects me to Country. I cried when I saw her burned

The continued marginalisation of Aboriginal people diminishes all of us – in terms of our values in living within a just society.

It was never acceptable to silence Aboriginal people in responses to major disasters. It’s incumbent upon us all to ensure these colonial practices of erasure and marginalisation are relegated to the past.

Authors: Bhiamie Williamson, Research Associate & PhD Candidate, Australian National University