Coronavirus modelling shows the government is getting the balance right - if our aim is to flatten the curve

- Written by Tony Blakely, Professor of Epidemiology, University of Melbourne

Australian government recently endorsed stricter social distancing measures to tackle the spread of the coronavirus, requiring four square metres of space per person in an enclosed room. This came only two days after it limited non-essential indoor gatherings to no more than 100 people. The situation is changing quickly, and the prime minister announced the national cabinet will meet to consider further restrictions.

With the number of cases around the world increasing rapidly and countries taking different measures, there is considerable concern and debate about if and when to start more drastic social or physical distancing measures.

Read more: The case for Endgame C: stop almost everything, restart when coronavirus is gone

What is the right social distancing policy for Australia if we are flattening the curve?

Should we close schools and workplaces? And should this happen now? My analysis and modelling of the situation suggests this is unlikely to be our best strategy — just yet. If our endgame is to flatten the curve, a steadily increasing amount of social distancing over the coming weeks is the best way to go.

This is the approach the government appears to be taking. To assist people to understand what is happening, and will happen in the future, I have assembled a model of how the COVID-19 epidemic will play out based on four different implementations of social distancing measures. It’s not perfect – but the patterns it produces are useful and likely close to the truth (we will not really know the truth for months).

Four different social distancing policy scenarios

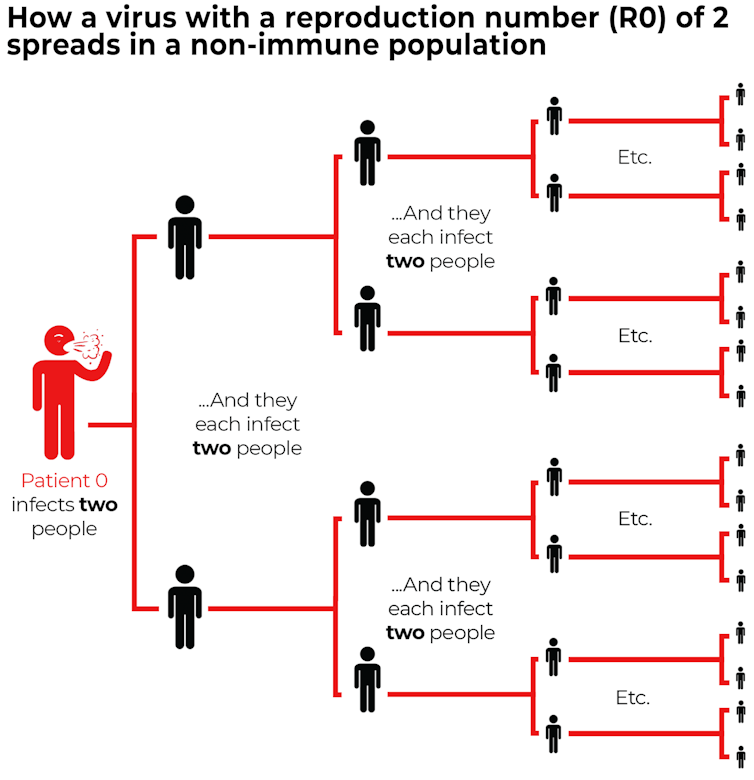

The model simulates different levels of social distancing by varying the reproductive rate (R0) of the virus. The R0 value refers to the number of people an infected person will transmit COVID-19 to if everyone they contact is susceptible.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

The model assumes the number of cases was doubling every four days in mid-March, and allows for a diminishing pool of susceptible people as the epidemic progresses.

I have not specifically modelled the elderly and those with chronic diseases. For these people, social isolation now is warranted given their higher risk of death if infected.

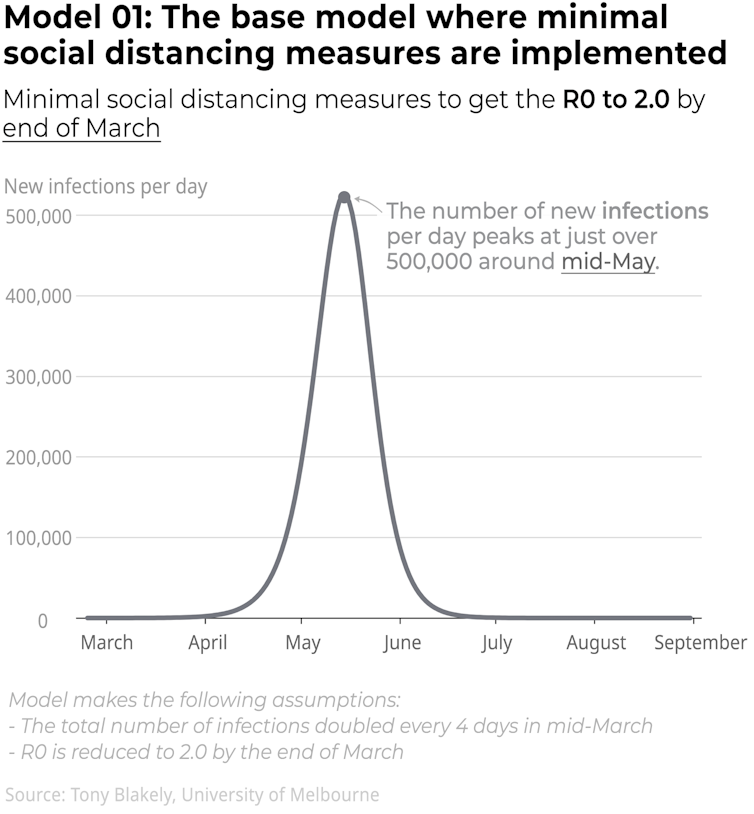

The result is unpleasant – disastrous even. New infections per day in Australia would peak at over 500,000 (and from estimates deduced from Imperial College model parameters, a third of which would be symptomatic), absolutely swamping health services.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

The model assumes the number of cases was doubling every four days in mid-March, and allows for a diminishing pool of susceptible people as the epidemic progresses.

I have not specifically modelled the elderly and those with chronic diseases. For these people, social isolation now is warranted given their higher risk of death if infected.

The result is unpleasant – disastrous even. New infections per day in Australia would peak at over 500,000 (and from estimates deduced from Imperial College model parameters, a third of which would be symptomatic), absolutely swamping health services.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Read more:

How we'll avoid Australia's hospitals being crippled by coronavirus

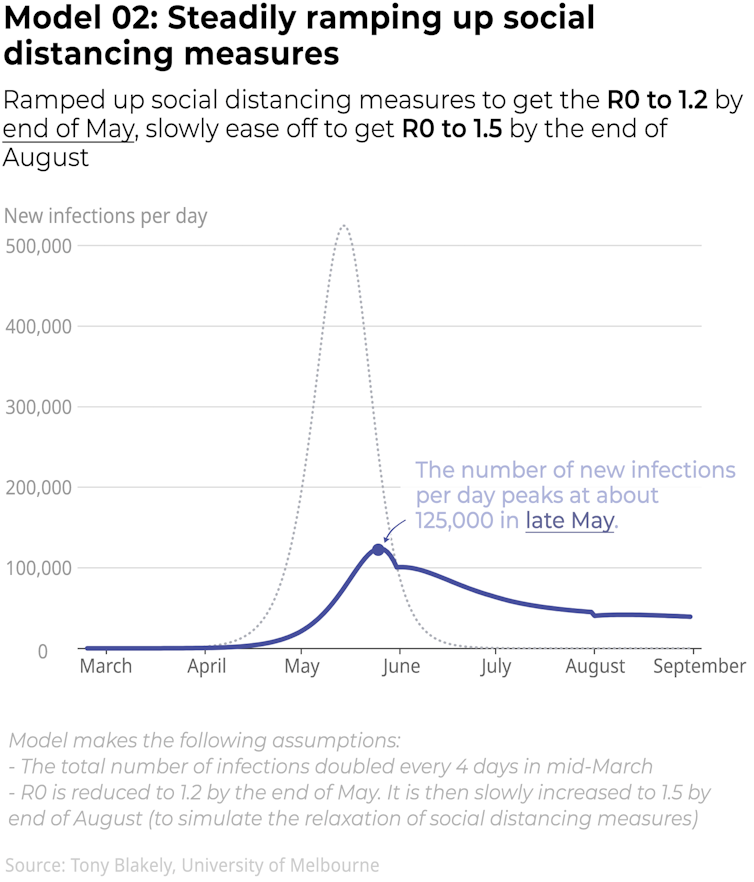

The second scenario approximates the current government policy of steadily increasing social distancing measures, simulated by reducing R0 from 2.5 to 1.2 by the end of May. The measures are then slowly relaxed, meaning R0 slowly increases. (There are an infinite number of options of when and by how much to relax social distancing). In this scenario the daily new infections peak at about 125,000 in late May, with the peak of symptomatic cases lagged up to a week – still not pleasant, but considerably better.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Read more:

How we'll avoid Australia's hospitals being crippled by coronavirus

The second scenario approximates the current government policy of steadily increasing social distancing measures, simulated by reducing R0 from 2.5 to 1.2 by the end of May. The measures are then slowly relaxed, meaning R0 slowly increases. (There are an infinite number of options of when and by how much to relax social distancing). In this scenario the daily new infections peak at about 125,000 in late May, with the peak of symptomatic cases lagged up to a week – still not pleasant, but considerably better.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

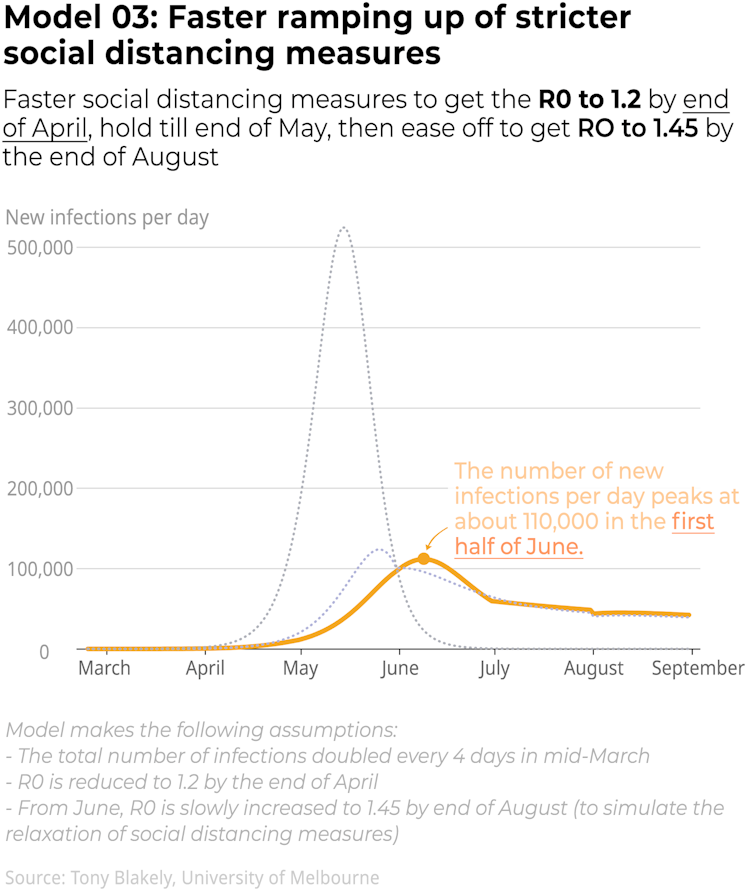

The third scenario models the case where social isolation measures are rolled out faster to get the R0 down to 1.2 by the end of April. This scenario pushes the peak of the epidemic to June, but does not significantly reduce the daily load of new cases compared to the previous model.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

The third scenario models the case where social isolation measures are rolled out faster to get the R0 down to 1.2 by the end of April. This scenario pushes the peak of the epidemic to June, but does not significantly reduce the daily load of new cases compared to the previous model.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

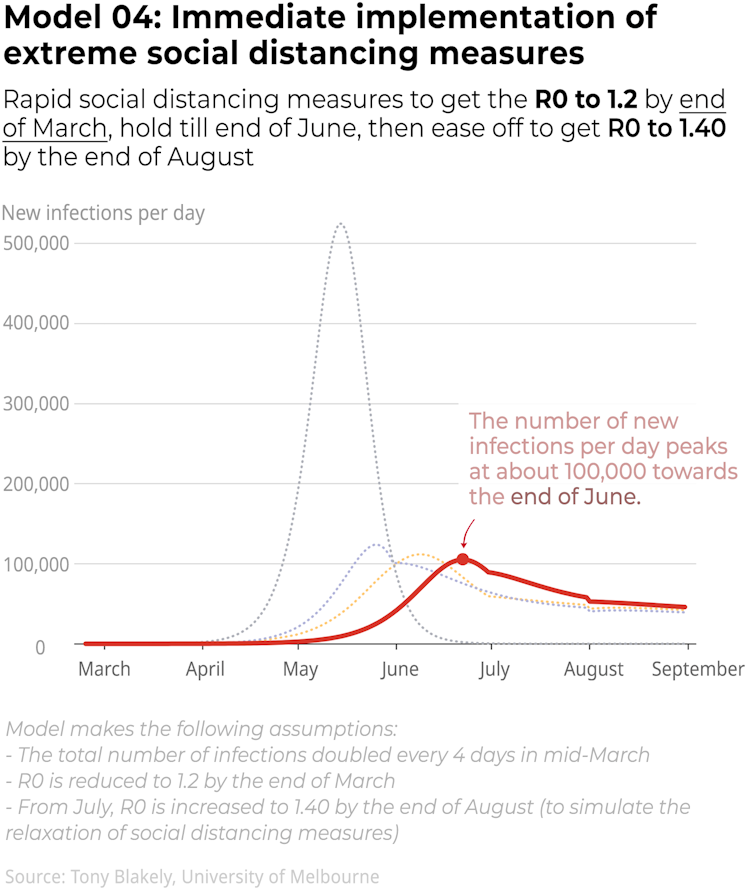

The final scenario models what will happen if we implement more drastic social distancing measures now, reducing R0 to 1.2 by the end of March. This approach reduces the peak number of new infections per day to about 100,000, which the model predicts will happen in mid- to late-June.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

The final scenario models what will happen if we implement more drastic social distancing measures now, reducing R0 to 1.2 by the end of March. This approach reduces the peak number of new infections per day to about 100,000, which the model predicts will happen in mid- to late-June.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

When compared to the scenario of steadily increasing social distancing measures, the last two strategies have the benefit of pushing peak caseloads in hospitals to early or late June. But the downside – and this is important – is that social distancing policies (with all their economic consequences and social disruption) will have to be in place for longer to achieve the same total number of cases at year’s end (the total cumulative number of cases by year’s end will depend on when and by how much social distancing is eased).

What happens to forecasts if the virus was actually spreading faster in mid-March?

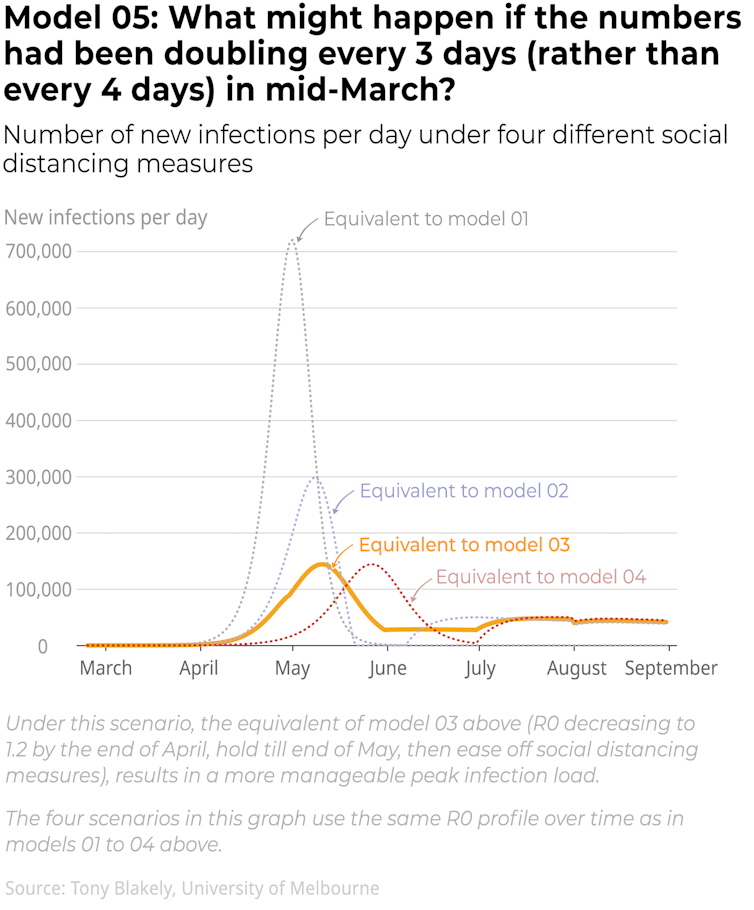

The above is what I think are reasonable modelling scenarios. However, what worries me is the possibility the cumulative number of infections is doubling every three days, not every four days as in the above models.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

When compared to the scenario of steadily increasing social distancing measures, the last two strategies have the benefit of pushing peak caseloads in hospitals to early or late June. But the downside – and this is important – is that social distancing policies (with all their economic consequences and social disruption) will have to be in place for longer to achieve the same total number of cases at year’s end (the total cumulative number of cases by year’s end will depend on when and by how much social distancing is eased).

What happens to forecasts if the virus was actually spreading faster in mid-March?

The above is what I think are reasonable modelling scenarios. However, what worries me is the possibility the cumulative number of infections is doubling every three days, not every four days as in the above models.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Under this assumption, implementing stricter social distancing measures faster (as per model 03 above) seems a prudent way to go. The health systems would not cope with the daily infection peak of 300,000 if we took till the end of May to fully implement policies (as per model 02 above).

Assuming the government is taking the “flattening the curve” strategy, this is presumably why it is not rushing to close schools and workplaces just yet. But such closures may soon be likely.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Under this assumption, implementing stricter social distancing measures faster (as per model 03 above) seems a prudent way to go. The health systems would not cope with the daily infection peak of 300,000 if we took till the end of May to fully implement policies (as per model 02 above).

Assuming the government is taking the “flattening the curve” strategy, this is presumably why it is not rushing to close schools and workplaces just yet. But such closures may soon be likely.

Authors: Tony Blakely, Professor of Epidemiology, University of Melbourne