The coronavirus and Chinese social media: finger-pointing in the post-truth era

- Written by Haiqing Yu, Associate Professor, School of Media and Communication, RMIT University

As public health authorities in China and the world fight the novel coronavirus, they face two major communication obstacles: the eroding trust in the media, and misinformation on social media.

As cities, towns, villages and residential compounds have been shut down or implemented curfews, social media have played a central role in crisis communication.

Chinese social media platforms, from WeChat and Weibo, to QQ, Toutiao, Douyin, Zhihu and Tieba, are the lifeline for many isolated and scared people who have been housebound for over two weeks, relying on their mobile phones to access information, socialise, and order food.

A meme being shared on WeChat reads: ‘When the epidemic is over, men will understand why women suffer from postnatal depression after one-month confinement upon childbirth.’

Author provided

A meme being shared on WeChat reads: ‘When the epidemic is over, men will understand why women suffer from postnatal depression after one-month confinement upon childbirth.’

Author provided

These platforms constitute the mainstream media in the war on the coronavirus.

I experienced the most extraordinary Chinese New Year with my parents in China and witnessed the power of Chinese social media, especially WeChat, in spreading and controlling information and misinformation.

China is not only waging a war against the coronavirus. It is engaged in a media war against misinformation and “rumour” (as termed by the Chinese authorities and social media platforms).

This banner being shared on WeChat reads: ‘Those who do not come clean when having a fever are class enemies hidden among the people.’

Author provided

This banner being shared on WeChat reads: ‘Those who do not come clean when having a fever are class enemies hidden among the people.’

Author provided

Information about the virus suddenly increased from January 21, after the central government publicly acknowledged the outbreak the previous day and Zhong Nanshan, China’s leading respiratory expert and anti-SARS hero, declared on the state broadcaster CCTV the virus was transmissible from person to person.

Read more: Coronavirus: how health and politics have always been inextricably linked in China

On WeChat, the Chinese all-in-one super app with over 1.15 billion monthly active users, there has been only one dominant topic: the coronavirus.

Rumour mongers and rumour busters

In Wired, Robert Dingwall wrote “fear, finger-pointing, and militaristic action against the virus are unproductive”, asking if it is time to adjust to a new normal of outbreaks.

To many Chinese, this new normal of fear and militaristic action is already real in everyday life.

Finger-pointing, however, can be precarious in the era of information control and post-truth.

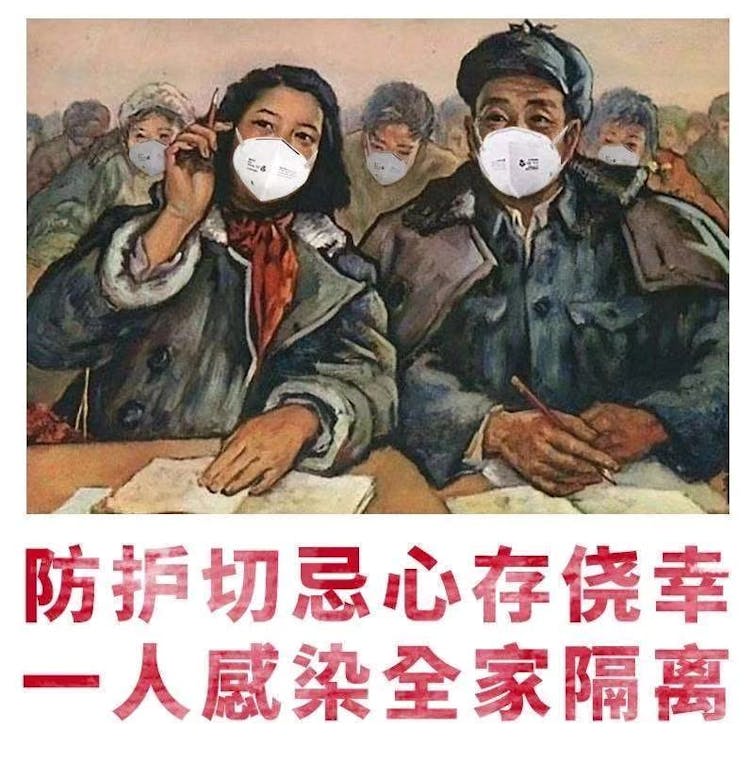

One of many spoof Cultural Revolution posters being shared on social media to warn people of the consequence of not wearing masks.

Author provided

One of many spoof Cultural Revolution posters being shared on social media to warn people of the consequence of not wearing masks.

Author provided

On WeChat and other popular social media platforms, information about the virus from official, semi-official, unofficial and personal sources is abundant in chat groups, “Moments”, WeChat official accounts, and newsfeeds (mostly from Tencent News and Toutiao).

Information includes personal accounts of life under lockdown, duanzi (jokes, parodies, humorous videos), heroism of volunteers, generosity of donations, quack remedies, scaremongering about deaths and price hikes, and the conspiracy theory of the US waging a biological war against China.

TikTok video (shared on WeChat) on the life of a man in isolation at home and his ‘social life’.There is also veiled criticism of the government and government officials for mismanagement, bad decisions, despicable behaviours and lack of accountability.

At the same time, the official media and Tencent have stepped up their rumour-busting effort.

They regularly publish rumour-busting pieces. They mobilise the “50-cent army” (wumao) and volunteer wumao (ziganwu) as their truth ambassadors.

Tencent has taken on the responsibility to provide “transparent” communication. It opened a new function through its WeChat mini-program Health, providing real-time updates of the epidemic and comprehensive information – including fake news busting.

The government has told people to only post and forward information from official channels and warned of severe consequences for anyone found guilty of disseminating “rumours”, including permanently blocking WeChat groups, blocking social media accounts, and possible jail terms.

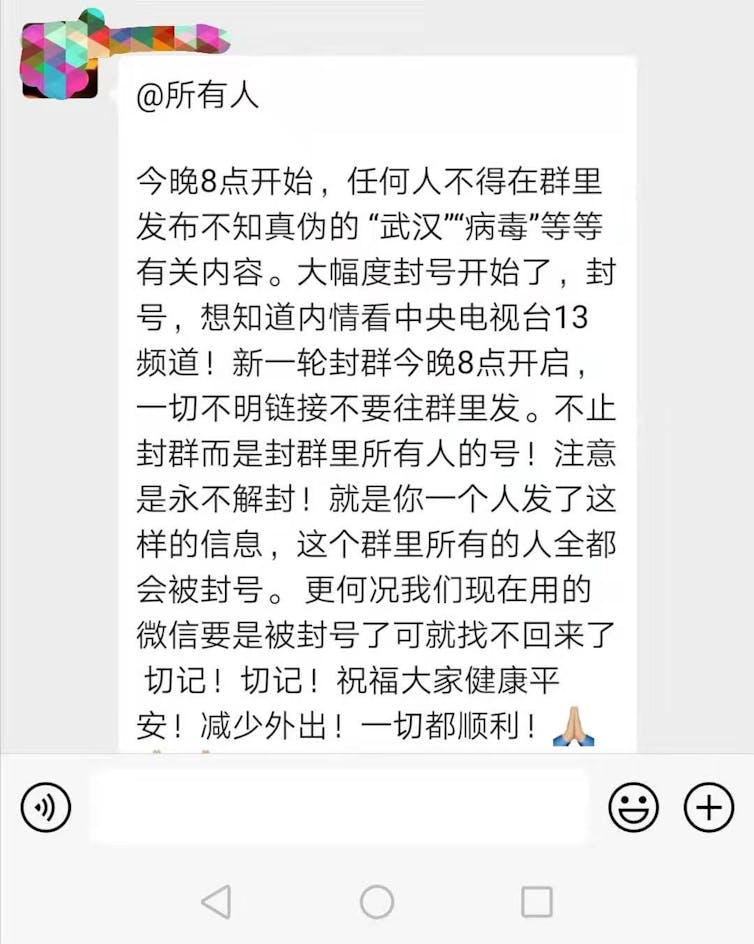

A warning to WeChat users not to spread fake news about the coronavirus.

Author provided

A warning to WeChat users not to spread fake news about the coronavirus.

Author provided

Chinese people, accustomed to having posts deleted, face increased peer pressure in their chat groups to comply with the heightened censorship regime. Amid the panic the general advice is: don’t repost anything.

They are asked to be savvy consumers, able to distinguish fake news, half-truths or rumours, and to trust only one source of truth: the official channels.

But the skills to detect and contain false content are becoming rarer and more difficult to obtain.

Coronavirus and the post-truth

We live in the post-truth era, where every “truth” is driven by subjective, elusive, self-confirming and emotional “facts”.

Read more: Post-truth politics and why the antidote isn't simply 'fact-checking' and truth

Any news source can take you in the wrong direction.

We have seen that in the eight doctors from Wuhan who transformed from being rumourmongers to whistleblowers and heroes within a month.

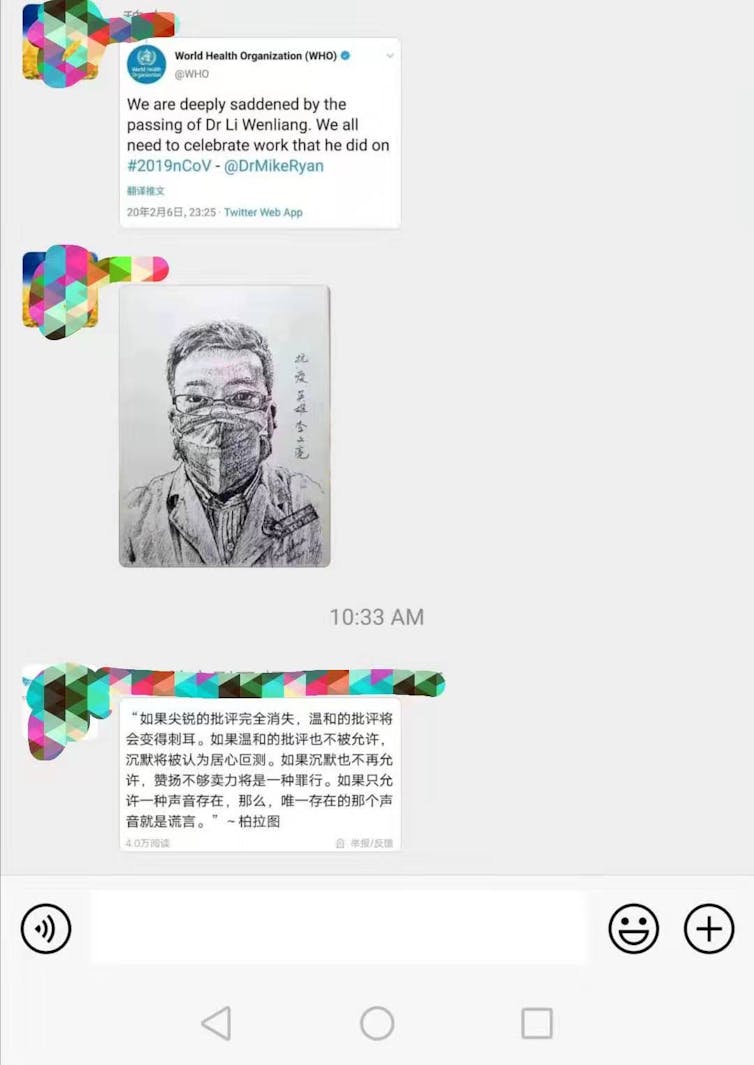

Dr Li Wenliang, the first to warn others of the “SARS-like” virus in December 2019, died from the novel coronavirus in the early hours of February 7 2020. There is an overwhelming sense of loss, mourning and unspoken indignation at his death in various WeChat groups.

WeChat users mourning the death of Dr Li Wenliang.

Author provided

WeChat users mourning the death of Dr Li Wenliang.

Author provided

In the face of this post-truth era, we must ask the questions: what is “rumour”, who defines “rumour”, and how does “rumour” occur in the first place?

Information overload is accompanied by information pollution. Detecting and contain false information on social media has been a technical, sociological and ideological challenge.

With a state-led campaign to “bust rumours” and “clean the web” in a controlled environment at a time of crisis, these questions are more urgent than ever.

As media scholar Yong Hu said in 2011, when “official lies outpace popular rumors” the government and its information control mechanism constitute the greatest obstruction of the truth.

On the one hand, the government has provided an environment conducive to the spread of rumours, and on the other it sternly lashes out against rumours, placing itself in the midst of an insoluble contradiction.

As the late Dr Li Wenliang said: “[To me] truth is more important than my case being redressed; a healthy society should not only allow one voice.”

A screenshot from WeChat quoting Dr Li Wenliang: ‘[To me] truth is more important than my case being redressed; a healthy society should not only allow one voice.’

Author provided

A screenshot from WeChat quoting Dr Li Wenliang: ‘[To me] truth is more important than my case being redressed; a healthy society should not only allow one voice.’

Author provided

China can lock down its cities, but it cannot lock down rumours on social media.

In fact, the Chinese people are not worried about rumours. They are worried about where to find truth and voice facts: not one single source of truth, but multiple sources of facts that will save lives.

Authors: Haiqing Yu, Associate Professor, School of Media and Communication, RMIT University