The old road rules no longer apply: how e-scooters challenge outdated assumptions

- Written by Elaine Stratford, Professor of Geography, University of Tasmania

Many people want changes to the law to deal with the increased use of e-scooters in Australia.

In general, the debate appears to be concerned mainly with safety and the different rates at which things move. Walking pedestrians are slower, motor vehicles are faster. Road infrastructure is not often designed for mixed uses.

I would argue both that the current debate is based on outdated assumptions about transport, transport technology and road users, and that it is now time to rethink the assumptions underpinning the Australian Road Rules. At present, for example, the Rules do not account for the emergence and adoption of new forms of transport like e-scooters, nor for other transport technologies that might morph from “recreational” devices such as hoverboards or segues.

A more creative approach would be to consider the larger opportunities that could transform how we move and connect. We could make transport more equitable, more sustainable and safer for all road users by rewriting the rules and retrofitting roads.

Road rules reflect assumptions about transport

Living in safe communities and benefiting from effective transport infrastructure means observing the Australian Road Rules. These rules are a national model that gives consistency to state and territory laws.

Under the rules, roads are areas on which to drive or ride motor vehicles (s.12.1). The definition of motor vehicles excludes motorised scooters (p.329).

Roads are complex spaces. Roads include shoulders (kerbed areas, unsealed sections, and sealed sections outside edge lines) and exclude bicycle, foot or shared paths (s.12.3). Different from shoulders, road-related areas comprise things that divide roads: footpaths and nature strips; public access areas used by animals or cyclists; and public areas on which to drive, ride, or park (s.13.1.d).

Users of wheeled recreational devices or wheeled toys are classed as pedestrians, even though they could use them for transport.

Author provided

Users of wheeled recreational devices or wheeled toys are classed as pedestrians, even though they could use them for transport.

Author provided

The rules define road users as drivers, riders, passengers and pedestrians (s.14). Pedestrians include users of motorised and non-motorised wheelchairs and those pushing either type of wheelchair (s.18.a–c), and speed limits apply. Importantly, users of wheeled recreational devices or wheeled toys are also pedestrians (s.18.c–d).

Wheeled recreational devices are “built to transport a person” even though they are “ordinarily used for recreation or play” (Australian Road Rules, p.338). They include roller blades and skates, skateboards, unicycles and all forms of scooter. In contrast, wheeled toys exclude motorised scooters, but include objects such as tricycles, and apply to children under 12.

The rules are to keep people and property safe — a goal also shaped but often overshadowed by economic imperatives. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), 1.34 million road deaths worldwide in 2016 amounted to the eighth leading cause of death. There were also 50 million injuries. Indeed, the WHO reports that road traffic injuries lead the cause of death for those aged five to 29, and the “burden is disproportionately borne by pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists”.

Australia’s road safety record is comparatively sound, worth noting for a population that, in 2018, numbered over 24 million and had over 18 million registered vehicles, including almost 17 million cars and four-wheeled light vehicles. Even so, in 2016 the WHO reported 1,351 road traffic fatalities in Australia: 45% were drivers, 16% passengers and 14% pedestrians (including those on wheeled devices). These statistics mirror those in Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the USA.

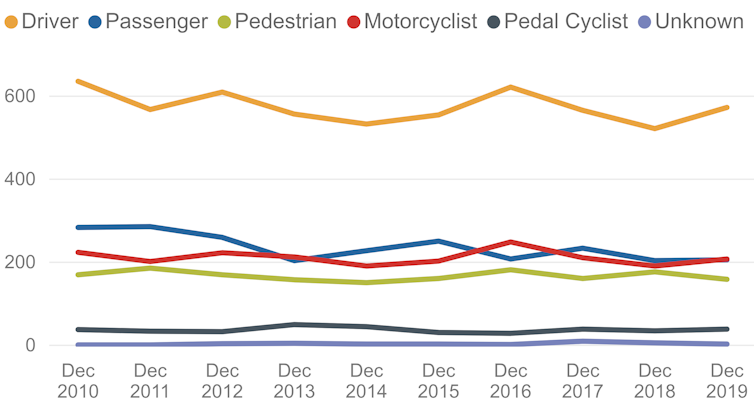

Twelve-month death tolls for road user categories.

Source: Australian Road Deaths Database

Twelve-month death tolls for road user categories.

Source: Australian Road Deaths Database

No matter how sound the road rules, and no matter how carefully we observe them, people die on roads. Among the reasons for that are the different speeds at which we move and the fact that our transport infrastructures cater poorly to mixed uses.

The case for retrofitting roads

Understandably, the Australian Road Rules are supposed to ensure transport infrastructures are used in ways for which they were designed or for which they can reasonably be adapted. That is why the rules put such emphasis on zones, speed limits, lines and signs — none of which, granted, can determine our safe or unsafe practices.

But what is reasonable? The rules reveal several possibly unreasonable assumptions about pedestrians who use wheeled devices.

For example, rule definitions emphasise recreation and play and lag behind real change among (mostly) young people opting to use such devices as transport. Legally they can, but road and road-related infrastructure simply does not accommodate that shift. It could.

E-scooters represent a real shift in urban transport paradigms.

Brett Sayles/Pexels

E-scooters represent a real shift in urban transport paradigms.

Brett Sayles/Pexels

So, as well as ensuring all road users continue to be safe as new technologies such as e-scooters come online, surely politicians and policymakers at all levels of government must be encouraged to see the larger opportunities.

We know that walking produces among the most democratic spaces of city life. There is every possibility to extend our thinking about that pedestrian act and consider how to embed wheeled devices into the urban fabric. Elsewhere, I have referred to such opportunities as ones that foster the geographies of generosity.

We are, I think, missing the chance to have creative conversations leading to innovative systems of radically retrofitted transport networks that are safe, have amenity, produce environmental gains and continue to democratise social life. Road networks take up great tracts of urban land, but it is possible to retrofit them for just, more equitable and more sustainable outcomes.

We could generate powerfully creative ideas about retrofitting what we have and make much stronger commitments to do that. Those ideas could translate to economic activity and might save lives.

Authors: Elaine Stratford, Professor of Geography, University of Tasmania