Housing crisis? What crisis? How politicians talk about housing and why it matters

- Written by Iain White, Professor of Environmental Planning, University of Waikato

Politicians in many countries around the world claim to be experiencing a “housing crisis”. But how do they define it, who is affected, and what is the cause?

These are critical questions. Exploring them can help us understand why much of the evidence from research is not carried through into political discourse and policy.

In the wake of the growing global “crisification” of housing, our research evaluated political speeches in Hansard connected to the housing crisis in New Zealand over three terms of the centre-right National Party government (2008-17). We sought to better understand how the issue became visible in politics and then trace this through to policy. We found the term “housing crisis” was rarely used before 2013.

Our aim was to provide deeper insights into why the problem appears to be resisting resolution. While the research took place in New Zealand, the findings have wider relevance for other countries grappling with this issue of “housing crisis”.

Read more: Housing policy reset is overdue, and not only in Australia

Tracing the rise of the housing crisis

Crises are truth claims. They are invoked, they define, they blame and, in doing so, they privilege certain ideologies or policy “solutions” over others.

If the problem is seen as due to “red tape”, too much immigration or unfair taxes, then these all require very different interventions. Some responses will be more effective than others. Some may have more in common with long-held political ideology than a body of scientific evidence.

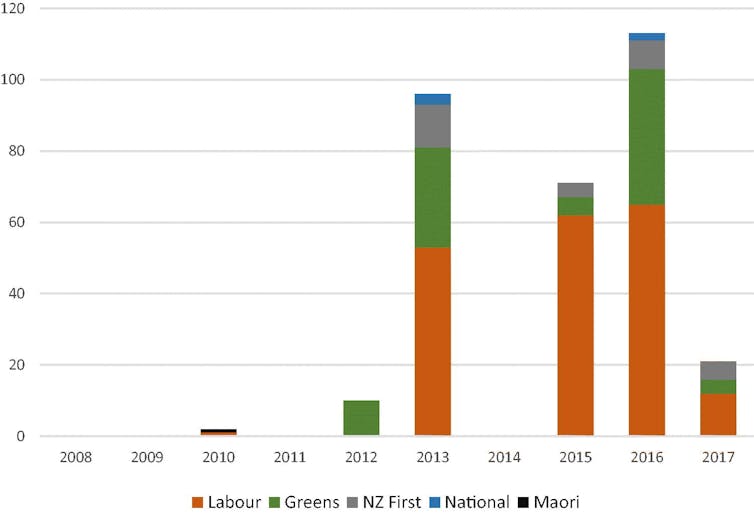

The chart below shows the emergence, frequency and party-oriented nature of housing being framed in terms of a “crisis”.

Frequency of the ‘housing crisis’ framing by year and political party.

Author provided

Frequency of the ‘housing crisis’ framing by year and political party.

Author provided

From being used only two times during the first term of National government (2008-11), the term was used 105 times in the second (2011-14) and 205 times in the third (2014-17). (The lack of use in 2014 appears more related to parliament being distracted by an election year than the profile of the issue.)

You can also see it’s almost exclusively opposition parties, in particular Labour and the Greens, that use the crisis framing. MPs from the ruling National Party used the term only five times, and then mainly in response to previous speakers to resist the charge.

A contest to frame the issue

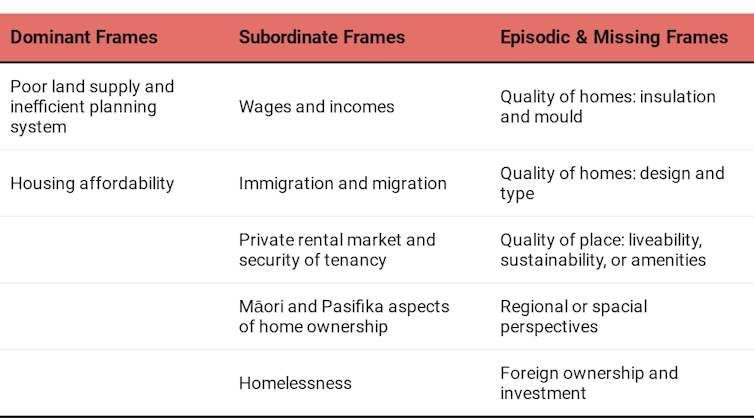

Turning to the content of debate, the following table provides an overview of the strength and focus of the framing themes used.

Author provided

Even though the governing party resisted the crisis terminology, a very consistent narrative dominated housing debates. It was that the reason for poor affordability was an inefficient and overly bureaucratic planning system that stifled the release of development land. It was a problem of supply, the reasoning went: more land should logically lead to more houses to meet demand, which should make housing more affordable.

In some ways the subordinate counterframing attempts by opposition parties provide an insight into the complexity of the housing crisis. In contrast, the government framing appears both easier to communicate and “solve”.

The episodic and missing frames are of particular interest as they help demonstrate what perspectives and voices were not represented in any meaningful manner.

Even though the National government did not accept the framing as a crisis, the high profile of the political discourse led to a suite of legislative and policy initiatives. These documents strongly reflect the dominant narrative. For example, the Resource Management Act, the main planning legislation in New Zealand, receives repeated blame for high house prices as part of the justification for measures aimed at increasing the supply of land.

Read more:

Three times citizens mobilised to put affordable housing on the political agenda

What does this mean for evidence and policy?

A key finding is that the crisis claim from opposition parties did not just lead to a contest over whether this was correct, or even its meaning. It also opened up a new political space for the ruling party to promote long-standing ideas about the preferred relationship between the state, private sector and market.

Researchers recognise housing as a multifaceted public policy problem and draw upon multiple streams of evidence. However, the political framing of housing as a crisis and its links to policy was much more simple, siloed and ideological. Although wider political discourse did acknowledge the complexity of housing issues, the nature of politics and the balance of power meant the cause was reduced to a simple effective message – poor land supply and an inefficient planning system – which informed the policy responses.

This gap between evidence and politics may also help explain how various urban and environmental crises have become less of a one-off event and more of a modern lived condition that may never be “solved” but rather redistributed politically.

In reality, the various frames show how there is not just a singular “housing crisis”. There may be a supply crisis, a demand crisis, a quality crisis, a distribution crisis, a credit crisis, a rental crisis, and so on. All of these issues differ between local, national and international contexts.

Read more:

Ideas of home and ownership in Australia might explain the neglect of renters’ rights

Lastly, if political power and existing ideological perspectives are so central to the framing and response to a crisis, then this raises questions for how researchers can better integrate research into politics and policy. While topics such as liveability, sustainability, density, connectivity, justice and quality are well represented in research, the data show this is not carried through into political discourse. Perhaps by focusing on the reasons for this gap we can better understand policy failure and the role of power and ideology in perpetuating the housing crisis.

Author provided

Even though the governing party resisted the crisis terminology, a very consistent narrative dominated housing debates. It was that the reason for poor affordability was an inefficient and overly bureaucratic planning system that stifled the release of development land. It was a problem of supply, the reasoning went: more land should logically lead to more houses to meet demand, which should make housing more affordable.

In some ways the subordinate counterframing attempts by opposition parties provide an insight into the complexity of the housing crisis. In contrast, the government framing appears both easier to communicate and “solve”.

The episodic and missing frames are of particular interest as they help demonstrate what perspectives and voices were not represented in any meaningful manner.

Even though the National government did not accept the framing as a crisis, the high profile of the political discourse led to a suite of legislative and policy initiatives. These documents strongly reflect the dominant narrative. For example, the Resource Management Act, the main planning legislation in New Zealand, receives repeated blame for high house prices as part of the justification for measures aimed at increasing the supply of land.

Read more:

Three times citizens mobilised to put affordable housing on the political agenda

What does this mean for evidence and policy?

A key finding is that the crisis claim from opposition parties did not just lead to a contest over whether this was correct, or even its meaning. It also opened up a new political space for the ruling party to promote long-standing ideas about the preferred relationship between the state, private sector and market.

Researchers recognise housing as a multifaceted public policy problem and draw upon multiple streams of evidence. However, the political framing of housing as a crisis and its links to policy was much more simple, siloed and ideological. Although wider political discourse did acknowledge the complexity of housing issues, the nature of politics and the balance of power meant the cause was reduced to a simple effective message – poor land supply and an inefficient planning system – which informed the policy responses.

This gap between evidence and politics may also help explain how various urban and environmental crises have become less of a one-off event and more of a modern lived condition that may never be “solved” but rather redistributed politically.

In reality, the various frames show how there is not just a singular “housing crisis”. There may be a supply crisis, a demand crisis, a quality crisis, a distribution crisis, a credit crisis, a rental crisis, and so on. All of these issues differ between local, national and international contexts.

Read more:

Ideas of home and ownership in Australia might explain the neglect of renters’ rights

Lastly, if political power and existing ideological perspectives are so central to the framing and response to a crisis, then this raises questions for how researchers can better integrate research into politics and policy. While topics such as liveability, sustainability, density, connectivity, justice and quality are well represented in research, the data show this is not carried through into political discourse. Perhaps by focusing on the reasons for this gap we can better understand policy failure and the role of power and ideology in perpetuating the housing crisis.

Authors: Iain White, Professor of Environmental Planning, University of Waikato