How does bushfire smoke affect our health? 6 things you need to know

- Written by Phoebe Roth, Deputy Editor, Health+Medicine

As bushfires continue to burn around Australia, smoke has continued to blanket major cities and regional areas.

Smoke emissions from the Australian bushfires from December 18, 2019 to January 17, 2020.Sydney and Canberra have now suffered on and off for months. While the smoke has affected Melbourne to a lesser extent, today Melbourne and large parts of country Victoria are hazy again.

On many days the smoke has meant air quality in these areas has far exceeded safe levels.

But what do these “hazardous” levels of air pollution actually mean for our health? Over this bushfire season, we’ve asked several experts to answer this question. Here we summarise The Conversation’s essential reading on bushfire smoke.

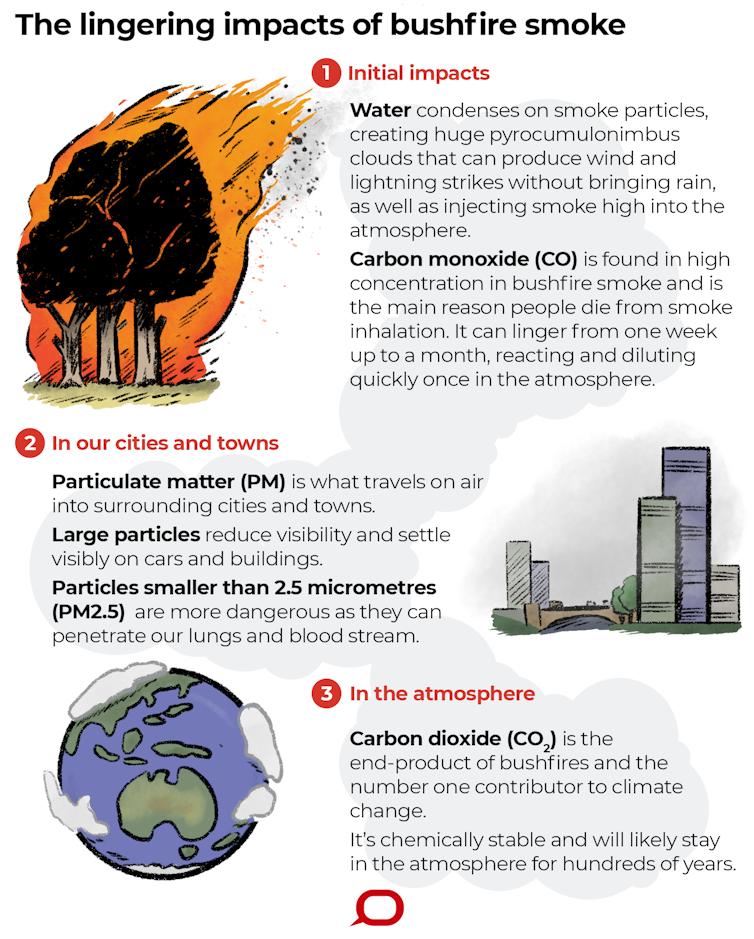

1. What’s in bushfire smoke?

Let’s take a look at what kind of chemicals are contained in bushfire smoke to make it dangerous.

Gabriel da Silva, who researches the chemistry of air pollution, explained smoke contains gases, most notably carbon dioxide (CO₂) and carbon monoxide (CO). It also contains traces of many other pollutants such as sulfur dioxide (SO₂) and nitrogen dioxide (NO₂). These gases can be toxic to the environment and human health.

While there’s no safe level of air pollution, bushfire smoke is particularly hazardous because of the presence of tiny particles, or particulate matter (PM).

This is both soot that builds up during combustion, and ash that breaks down from the remnants of burnt fuel. These particles can penetrate deep into our lungs and make their way into our bloodstream, potentially impacting almost every bodily system.

The PM we’re most concerned about are PM2.5 – particles less than 2.5 micrometres in size. The concentration of PM2.5 in the air is often the marker we use to assess air quality.

Read more: Bushfire smoke is everywhere in our cities. Here's exactly what you are inhaling

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

2. It’s hard to breathe

You might have experienced an irritated throat and coughing from the bushfire smoke. This is because of the particles (the tiny ones and slightly larger ones) irritating the thin lining of your respiratory tract, called the mucous membrane. This can happen in otherwise healthy people.

But as Brian Oliver wrote, people with pre-existing respiratory conditions such as asthma are at risk of more severe breathing difficulties in the bushfire smoke.

In periods of smoke haze, people have called the ambulance more frequently for breathing difficulties, and larger numbers than usual have presented to hospital emergency departments with breathing problems.

Read more:

How does poor air quality from bushfire smoke affect our health?

Some people suffering in the smoke might have undiagnosed asthma. Christine Jenkins explained signs to look out for include chest tightness and wheezing in response to exposure to irritants such as smoke, dusts, aerosol sprays and fumes.

If you think you may have asthma, to avoid any long-term damage, it’s important to see a doctor to have it diagnosed and treated.

Read more:

I'm struggling to breathe with all the bushfire smoke – could I have undiagnosed asthma?

People with other pre-existing health issues, such as heart conditions – often older people – are also at higher risk of illness and death when the air quality is poor. One study reported a 5% increase in deaths during bushfire smoke events in Sydney from 1994 to 2007, such as from heart attacks.

3. My eyes are irritated

When smoke comes into contact with our eyes, the fumes and small particles dissolve into our tears and coat the eye’s surface. In some people, this can trigger inflammation, and therefore irritation.

Katrina Schmid and Isabelle Jalbert explained studies in countries with routinely high levels of air pollution report higher levels of chronic dry eye.

While dry eye is a result of damage to the surface of the eyes, it’s also possible pollutants entering the blood stream after we breathe them in could affect the blood supply to the eye. This in turn could damage the fine vessels within the eye itself.

But we need more research into the long-term effects of prolonged poor air quality on our eyes, particularly from bushfire smoke.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

2. It’s hard to breathe

You might have experienced an irritated throat and coughing from the bushfire smoke. This is because of the particles (the tiny ones and slightly larger ones) irritating the thin lining of your respiratory tract, called the mucous membrane. This can happen in otherwise healthy people.

But as Brian Oliver wrote, people with pre-existing respiratory conditions such as asthma are at risk of more severe breathing difficulties in the bushfire smoke.

In periods of smoke haze, people have called the ambulance more frequently for breathing difficulties, and larger numbers than usual have presented to hospital emergency departments with breathing problems.

Read more:

How does poor air quality from bushfire smoke affect our health?

Some people suffering in the smoke might have undiagnosed asthma. Christine Jenkins explained signs to look out for include chest tightness and wheezing in response to exposure to irritants such as smoke, dusts, aerosol sprays and fumes.

If you think you may have asthma, to avoid any long-term damage, it’s important to see a doctor to have it diagnosed and treated.

Read more:

I'm struggling to breathe with all the bushfire smoke – could I have undiagnosed asthma?

People with other pre-existing health issues, such as heart conditions – often older people – are also at higher risk of illness and death when the air quality is poor. One study reported a 5% increase in deaths during bushfire smoke events in Sydney from 1994 to 2007, such as from heart attacks.

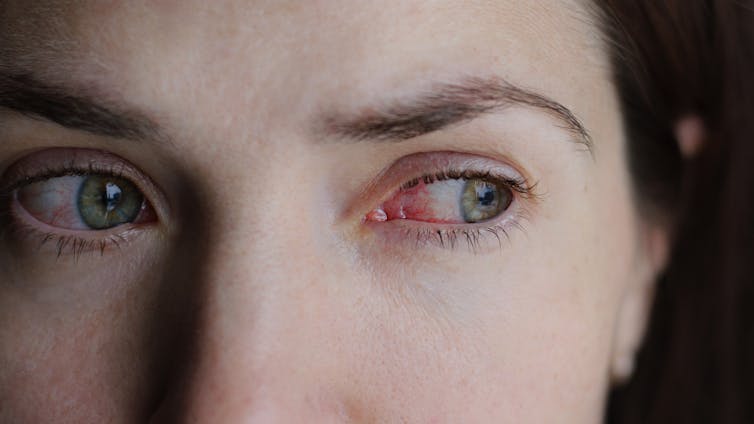

3. My eyes are irritated

When smoke comes into contact with our eyes, the fumes and small particles dissolve into our tears and coat the eye’s surface. In some people, this can trigger inflammation, and therefore irritation.

Katrina Schmid and Isabelle Jalbert explained studies in countries with routinely high levels of air pollution report higher levels of chronic dry eye.

While dry eye is a result of damage to the surface of the eyes, it’s also possible pollutants entering the blood stream after we breathe them in could affect the blood supply to the eye. This in turn could damage the fine vessels within the eye itself.

But we need more research into the long-term effects of prolonged poor air quality on our eyes, particularly from bushfire smoke.

Many people have found the bushfire smoke has irritated their eyes.

From shutterstock.com

If your eyes are irritated, flush them as often as you can, with over-the-counter lubricant eye drops if you have some on hand. If not, use sterile saline solution or clean bottled water. You can also place a cool face washer over your closed lids.

Don’t rub your eyes, as this could make the irritation worse, and avoid wearing contact lenses.

Read more:

Bushfire smoke is bad for your eyes, too. Here's how you can protect them

4. I’m pregnant. Can the smoke harm my baby?

Many people have found the bushfire smoke has irritated their eyes.

From shutterstock.com

If your eyes are irritated, flush them as often as you can, with over-the-counter lubricant eye drops if you have some on hand. If not, use sterile saline solution or clean bottled water. You can also place a cool face washer over your closed lids.

Don’t rub your eyes, as this could make the irritation worse, and avoid wearing contact lenses.

Read more:

Bushfire smoke is bad for your eyes, too. Here's how you can protect them

4. I’m pregnant. Can the smoke harm my baby?

Pregnant women should take extra care to avoid exposure to bushfire smoke where possible.

From shutterstock.com

Pregnant women breathe at an increased rate, and their hearts need to work harder than those of non-pregnant people to transport oxygen to the fetus. This makes them particularly vulnerable to the effects of air pollution, including bushfire smoke.

As Sarah Robertson and Louise Hull wrote, research shows prolonged exposure to bushfire smoke increases the risk of pregnancy complications including high blood pressure, gestational diabetes, low birth weight and premature birth (before 37 weeks).

There’s also some evidence air pollution compromises fertility by reducing ovarian reserve (the number of eggs in the ovary) and affecting sperm number and movement.

Read more:

Pregnant women should take extra care to minimise their exposure to bushfire smoke

5. Long-term effects

Given this is a new phenomenon, we don’t know exactly what prolonged exposure to bushfire smoke could mean for future health.

But to get an idea, we can look at the health of populations that routinely experience high levels of air pollution. Brian Oliver pulled some of this data together.

He says air pollution is associated with an increased risk of several cancers, and chronic health conditions like respiratory and heart disease. The World Health Organisation estimates ambient air pollution contributes to 4.2 million premature deaths around the world every year.

A recent study in China reported long-term exposure to a high concentration of PM2.5 is associated with an increased risk of stroke.

While this can give us an indication, there are a couple of reasons we can’t rely too heavily on these findings. First, taking data from one type of airborne pollution and applying it to different pollutants is complex, as the chemical makeup is likely to differ between pollutants. And second, we are not (yet) looking at the long-term exposure to air pollution seen in countries like China.

Read more:

We know bushfire smoke affects our health, but the long-term consequences are hazy

6. How can we protect ourselves?

The acute effects of exposure to bushfire smoke are evident, and though we won’t know the long-term effects for some time, there’s a clear need to protect ourselves.

According to Lidia Morawska, staying inside provides some protection against bushfire smoke, but the degree of protection depends on the type of building and importantly, its ventilation.

One option to improve the quality of indoor air is to use air purifiers. Look out for air purifiers with a HEPA filter – these are the most efficient.

Pregnant women should take extra care to avoid exposure to bushfire smoke where possible.

From shutterstock.com

Pregnant women breathe at an increased rate, and their hearts need to work harder than those of non-pregnant people to transport oxygen to the fetus. This makes them particularly vulnerable to the effects of air pollution, including bushfire smoke.

As Sarah Robertson and Louise Hull wrote, research shows prolonged exposure to bushfire smoke increases the risk of pregnancy complications including high blood pressure, gestational diabetes, low birth weight and premature birth (before 37 weeks).

There’s also some evidence air pollution compromises fertility by reducing ovarian reserve (the number of eggs in the ovary) and affecting sperm number and movement.

Read more:

Pregnant women should take extra care to minimise their exposure to bushfire smoke

5. Long-term effects

Given this is a new phenomenon, we don’t know exactly what prolonged exposure to bushfire smoke could mean for future health.

But to get an idea, we can look at the health of populations that routinely experience high levels of air pollution. Brian Oliver pulled some of this data together.

He says air pollution is associated with an increased risk of several cancers, and chronic health conditions like respiratory and heart disease. The World Health Organisation estimates ambient air pollution contributes to 4.2 million premature deaths around the world every year.

A recent study in China reported long-term exposure to a high concentration of PM2.5 is associated with an increased risk of stroke.

While this can give us an indication, there are a couple of reasons we can’t rely too heavily on these findings. First, taking data from one type of airborne pollution and applying it to different pollutants is complex, as the chemical makeup is likely to differ between pollutants. And second, we are not (yet) looking at the long-term exposure to air pollution seen in countries like China.

Read more:

We know bushfire smoke affects our health, but the long-term consequences are hazy

6. How can we protect ourselves?

The acute effects of exposure to bushfire smoke are evident, and though we won’t know the long-term effects for some time, there’s a clear need to protect ourselves.

According to Lidia Morawska, staying inside provides some protection against bushfire smoke, but the degree of protection depends on the type of building and importantly, its ventilation.

One option to improve the quality of indoor air is to use air purifiers. Look out for air purifiers with a HEPA filter – these are the most efficient.

Masks will only be effective if they are fitted correctly.

Erik Anderson/AAP

Consider staying inside where possible on days where the air quality is very poor, particularly if you have a pre-existing condition or you’re pregnant.

As for face masks, regular fabric masks are ineffective as they allow the small particles to get through. P2/N95 masks are the most effective, but these need to be fitted correctly.

Of course, these are emergency measures that don’t in themselves represent a solution. As Morawska says, the only real way forward is to address the climate crisis urgently and decisively.

Read more:

From face masks to air purifiers: what actually works to protect us from bushfire smoke?

Masks will only be effective if they are fitted correctly.

Erik Anderson/AAP

Consider staying inside where possible on days where the air quality is very poor, particularly if you have a pre-existing condition or you’re pregnant.

As for face masks, regular fabric masks are ineffective as they allow the small particles to get through. P2/N95 masks are the most effective, but these need to be fitted correctly.

Of course, these are emergency measures that don’t in themselves represent a solution. As Morawska says, the only real way forward is to address the climate crisis urgently and decisively.

Read more:

From face masks to air purifiers: what actually works to protect us from bushfire smoke?

Authors: Phoebe Roth, Deputy Editor, Health+Medicine