Vital Signs: Australia's nation-building opportunity held hostage by the deficit daleks

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

As anticipated, the Australian government downsized a number of its economic forecasts in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) released this week.

Also as anticipated, the federal government did everything it could to retain its forecast budget surplus for 2019-20. Having pinned its economic-management credentials to one single economic statistic – remember those hokey phrases from the May budget, “back in the black” and “back on track” – it was never going to be otherwise.

Read more: 5 things MYEFO tells us about the economy and the nation’s finances

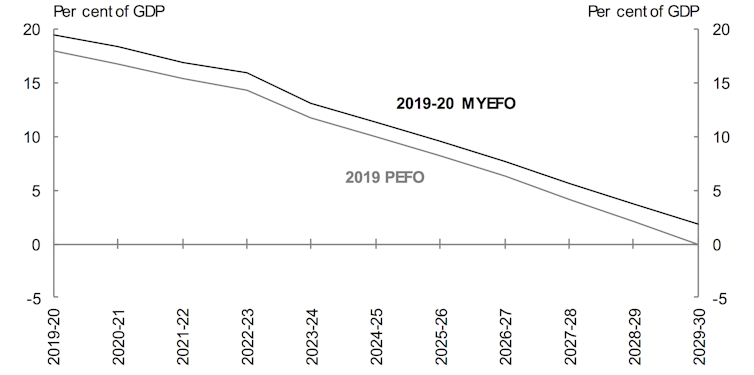

One casualty of the updated numbers is the forecast, made in May, that Australia’s net government debt would be reduced to zero by 2030. MYEFO projects that net debt in 2030 will instead be about 2% of GDP.

Australian Treasury net debt projections to 2029-30.

MYEFO 2019-20 Part 4: Debt Statement, CC BY

Australian Treasury net debt projections to 2029-30.

MYEFO 2019-20 Part 4: Debt Statement, CC BY

That is, essentially, a trivial difference. But it reveals a lot about the federal government’s view of fiscal management.

Governments living within their means

An oft-repeated line from Scott Morrison – one he used when he was treasurer as well as now he is prime minister – is that the government is “living within its means”.

If one doesn’t think about it too carefully, that phrase makes a lot of sense. Do we want governments not to live within their means?

But there’s a lot hidden in the words “live” and “means”.

The way the Morrison government likes to tell it, Australia pays a lot of interest on its foreign debt. According to official figures, the interest payment on the debt in 2018-19 was about A$14 billion.

That sounds like a lot, particularly when compared with, say, the amount of money the federal government spends on schools – A$19.6 billion in the past budget year, and about A$20.9 billion this year.

Such comparisons are made by members of the Morrison government (such as Treasurer Josh Frydenberg) quite a lot.

Yes, our interest bill is in the same ballpark as the federal government’s spending on schools. But school funding is a state responsibility. The NSW government alone spent A$17.3 billion on schools in 2018-19.

So the comparison between interest and spending on schools is misleading at best and disingenuous at worst.

If they wanted to, ministers could compare the interest payment with the amount of money the government collects from tobacco taxes – A$17.3 billion. That comparison makes our interest bill sound pretty small.

Read more: Vital Signs: why governments get addicted to smoking, gambling and other vices

Spending as an investment

What’s missing is the broader point that when the government borrows money to invest in social and physical infrastructure it can often generate returns far in excess of the interest cost.

Currently the federal government can borrow for ten years at an annual interest rate of about 1%. Investing in nation-building like road and rail infrastructure, schools, preventive medical care, mental health and recreational facilities would almost certainly generate a return of more than 1% a year.

If the government was a business it would jump at the opportunity to borrow at 1% and generate higher returns year after year (such as for education).

Read more: Vital Signs: it's time to borrow to build

But conservative governments – as political outfits – love the narrative of belt-tightening and living within one’s means.

Beware of boondoggles

To be fair, without some financial discipline low interest rates on government debt can also be used to justify every idiotic pork-barrel project imaginable. These routinely come up on both sides of politics. Think of the Rudd government’s disastrous “pink batts” scheme, or Barnaby Joyce’s inland rail scheme.

White elephants are easy to find when governments get involved in spending without proper cost-benefit analysis. I have proposed, with my colleagues Rosalind Dixon and Alex Rosenberg, a method for doing cost-benefit analysis more rigorously to take account of the broader social benefits of government spending.

Governments aren’t households

One very simple thing to remember is that governments are not like households.

You and I will will not be around forever. When we die our financial dealings will be tallied up. Most of us would like to pass on something to our children. If we have the means and the discipline, many of us do.

But governments don’t end. They represent a population that carries on indefinitely. Their success is not measured by what gets passed on at some end point. It’s measured by what they do for the public year after year.

Sometimes that can be improved by borrowing sensibly to invest in social and physical infrastructure.

Read more: Surplus before spending. Frydenberg's risky MYEFO strategy

In 2020 I hope we will hear less from Scott Morrison and his ministers about balanced budgets and debt elimination, and more about another phrase of his – “good debt” versus “bad debt”.

Australia is desperately in need of investment by the government – and sensible, nation-building infrastructure is definitely “good debt”.

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW