'Nothing quite prepares you for the impact of this exhibition': Haring Basquiat at the NGV

- Written by Sasha Grishin, Adjunct Professor of Art History, Australian National University

Review: Keith Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines, National Gallery of Victoria

In the 1980s, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring were the bad boys of the New York art scene who meteorically rose from street art notoriety to main street fame and glory.

In recent years, the National Gallery of Victoria has established a reputation for bold, startling and unexpected pairing of artists, for example Escher X Nendo or the Terracotta Warriors and Cai Guo-Qiang. With Basquiat and Haring, it is a case of natural selection.

The two artists were friends and occasional collaborators. They both – to some extent – came from a street art graffiti background. They were both exceptionally prolific. They both combined image and text and they were active participants in “the scene” where Andy Warhol was the undisputed godfather. They also both died tragically young – Basquiat was 27 and Haring 31.

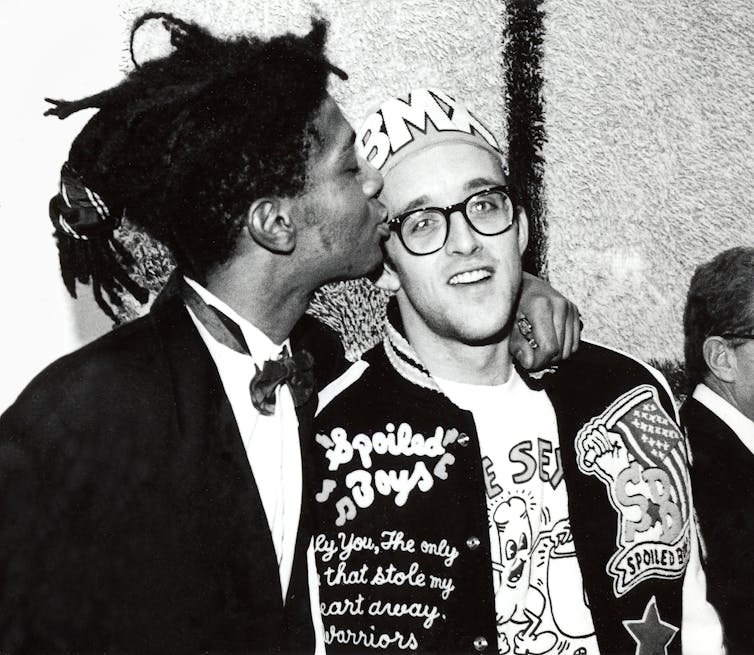

Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat at the opening reception for Julian Schnabel at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1987.

© George Hirose

Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat at the opening reception for Julian Schnabel at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1987.

© George Hirose

However, the two artists each developed a unique and distinctive pictorial language that had a profound impact on the course of American art and, more broadly, on art internationally. The vigour and energy of punk music, dress and dance, and the broader frame of reference of street culture morphed into an art form that found a place in museums.

New York art of the preceding generation saw the triumph of formalism – abstraction primarily concerned with the properties of the medium or Euclidean geometry, but turned away from society and the economic and political reality of the day. From the outset Basquiat and Haring engaged with everyday reality and shone a light on social and political causes. The world was out of joint and they each saw themselves as having a role in doing something about it.

Basquiat, in particular, fought against racism in America and against apartheid in South Africa. Haring fought the discrimination experienced by the gay and lesbian communities. Both were opposed to state coercion and police violence and protested the oppressive policies of Ronald Reagan with the punitive and destructive effects of Reaganomics.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, American, 1960-1988. Irony of a Negro Policeman, 1981. Synthetic polymer paint and oilstick on wood. 183.0 x 122.0 cm.

Private collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Jean-Michel Basquiat, American, 1960-1988. Irony of a Negro Policeman, 1981. Synthetic polymer paint and oilstick on wood. 183.0 x 122.0 cm.

Private collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

It is possible America under Trump brings back echoes of America under Reagan, making this exhibition appear particularly timely and relevant. There is nothing dated about this show – it tragically strikes as being about the here and now.

The National Gallery of Victoria exhibition brings together over 230 of the most significant works by the two artists. There is visual overload as the show snakes along from the early graffiti-like images (Haring reputedly did about 10,000 subway drawings), through to the classic hard-hitting paintings of the mid-80s, the spectacular “black light” room and their final works.

Installation view of Keith Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines at NGV International, 1 December 2019 – 11 April 2020.

© Estate of Jean - Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York © Keith Haring Foundation Photo: Sean Fenness

Installation view of Keith Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines at NGV International, 1 December 2019 – 11 April 2020.

© Estate of Jean - Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York © Keith Haring Foundation Photo: Sean Fenness

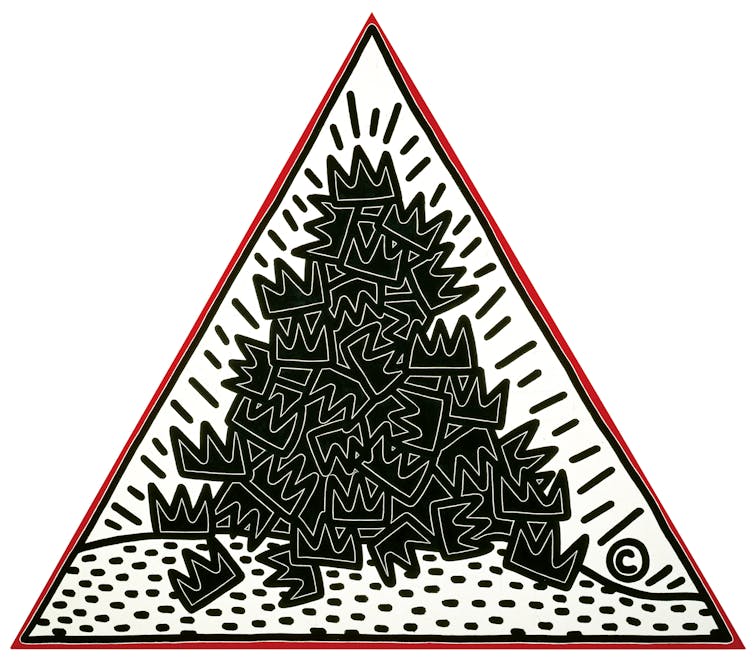

After Basquiat’s death from an overdose on 12 August 1988, Haring painted A Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat – a stunningly powerful work which, with visual lucidity, distilled Basquiat’s crown emblem into a tortured triumphant monument. Almost simultaneously, realising he was losing his battle with AIDS, Haring painted some of his final testament pieces before his own death on 16 February 1990.

Keith Haring, American, 1958 – 90. Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1988. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 304.8 x 304.8 x 304.8 cm.

The Keith Haring Foundation, New York © Keith Haring Foundation

Keith Haring, American, 1958 – 90. Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1988. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 304.8 x 304.8 x 304.8 cm.

The Keith Haring Foundation, New York © Keith Haring Foundation

Keith Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines may well be the riskiest exhibition the NGV has staged in its more than 150-year history. It is a raw and uncompromising show tackling many of the critical social, ethical and sexual issues that confront society head-on.

I spent quite a bit of time in New York in the 1980s, viewing a fair amount of the work of both artists, both inside and outside the galleries, and saw the Basquiat retrospective at the Whitney in 1992. However, nothing quite prepares you for the impact of this exhibition. It is confronting, highly emotional, intimate, intensely personal and, at times, excruciatingly honest.

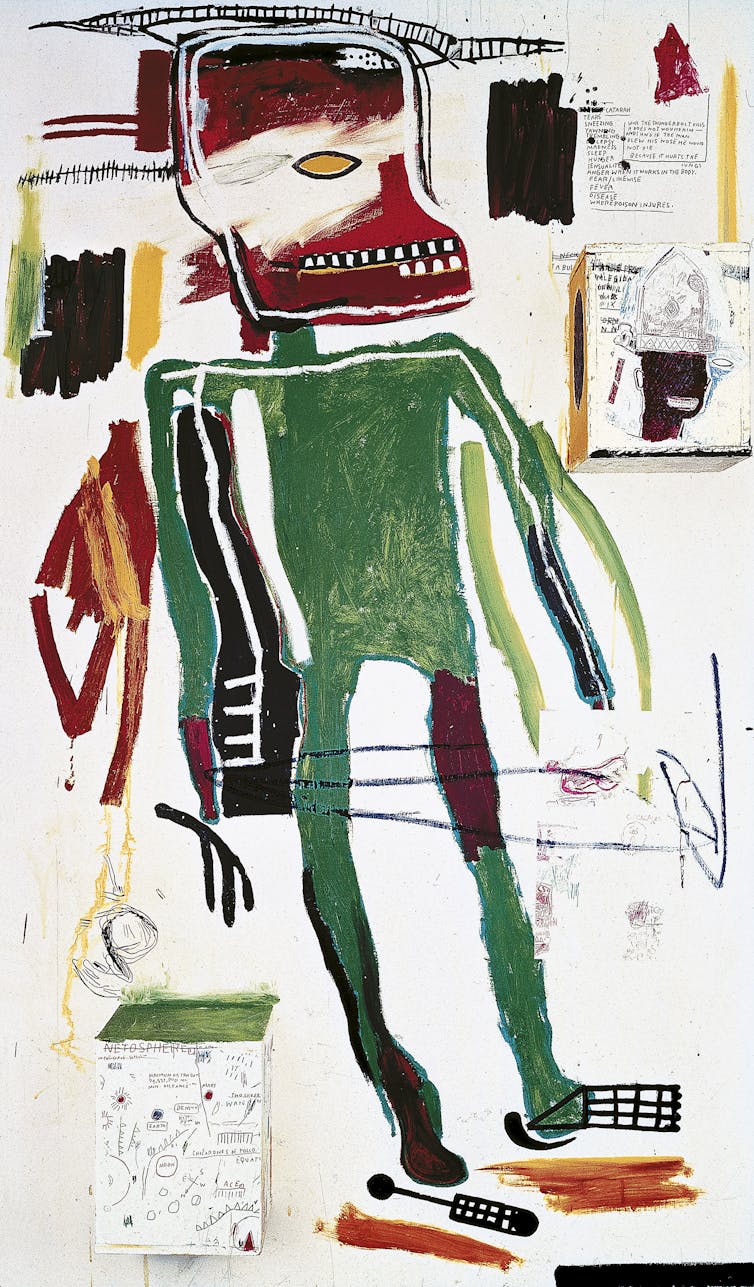

Basquiat was an intellectual artist. When confronting one of his major paintings, there is a considerable amount of unpacking of his rich frames of reference. These include not only his well-thumbed copy of Gray’s Anatomy or references to the writer, poet and intellectual William Burroughs, but also Fyodor Dostoevsky and a broad cross-section of art history.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, American, 1960-88, Because it Hurts the Lungs, 1986. Synthetic polymer paint and collage on wood 183.0 x 107.0 x 21.0 cm.

Museum MACAN, Jakarta © Estate of Jean - Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Jean-Michel Basquiat, American, 1960-88, Because it Hurts the Lungs, 1986. Synthetic polymer paint and collage on wood 183.0 x 107.0 x 21.0 cm.

Museum MACAN, Jakarta © Estate of Jean - Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Haring stripped his images down to bare essentials with a starkness and deceptive simplicity. Both artists had developed their own repertoire of emoji, or little visual ideograms – for example Haring’s radiant child and Basquiat’s crown – and these constantly recur throughout their art. Neither artist practised self-censorship and there is a substantial flow of consciousness in their art characteristic of artists coming from a graffiti background.

Considerable effort has been made in the display to provide a rich context for the show. This is done partly through video installations, including one showing Haring being arrested for drawing graffiti in subways, as well as others with dance and fashion sequences.

Keith Haring in New York City subway, New York, 1984.

Photograph: Tseng Kwong Chi © Muna Tseng Dance Projects Art © Keith Haring Foundation

Keith Haring in New York City subway, New York, 1984.

Photograph: Tseng Kwong Chi © Muna Tseng Dance Projects Art © Keith Haring Foundation

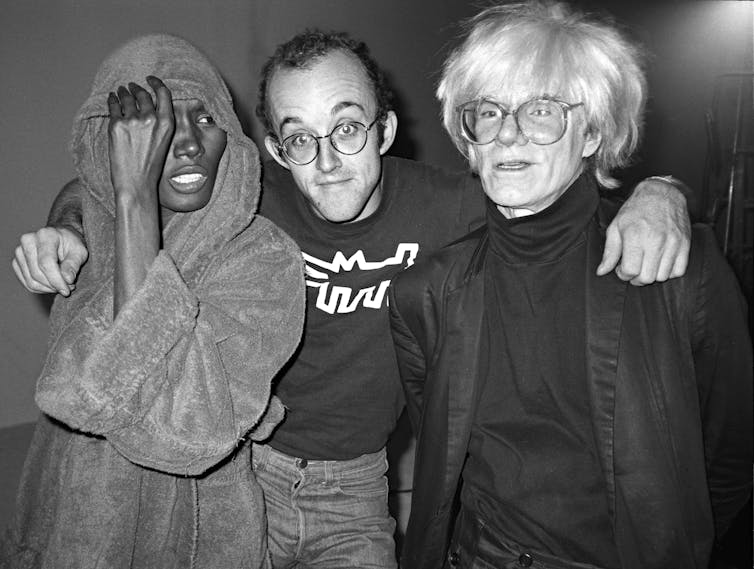

There are also numerous exquisite photographs from “the scene”, not only with the omnipresent Andy Warhol, but also of Basquiat’s girlfriend, later better known as the pop singer Madonna, and of Haring’s collaboration with the singer and performer Grace Jones. A beautifully edited, user-friendly and well-written, brick-like catalogue accompanies the show.

Grace Jones, Keith Haring, Andy Warhol at Paradise Garage, New York ,1983.

Photograph: Tseng Kwong Chi © Muna Tseng Dance Projects

Grace Jones, Keith Haring, Andy Warhol at Paradise Garage, New York ,1983.

Photograph: Tseng Kwong Chi © Muna Tseng Dance Projects

This exhibition may not be for everyone, but those who are fortunate enough to see it are unlikely to ever forget it.

Kieth Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines, National Gallery of Victoria (International), St Kilda Road, Melbourne, 1 December 2019 – 13 April 2020.

Authors: Sasha Grishin, Adjunct Professor of Art History, Australian National University