Hidden women of history: Frances Levvy, Australia's quietly radical early animal rights campaigner

- Written by Elaine Stratford, Professor, University of Tasmania

In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

We are all touched by relationships with animals — as domestic and working companions, wild inspirations, threats, or pests.

Some of us may know about the enduring worth of organisations such as the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Fewer of us may know about the 19th century foundations for animal advocacy among ordinary women beginning, more often, to find their voice in the public sphere.

The life of Frances Deborah Levvy (14 November 1831–29 November 1924) is worth revisiting because her ethical, political, and journalistic contributions speak to our current concerns for the more-than-human world.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Flos Greig, Australia’s first female lawyer and early innovator

A mainstay of the New South Wales’ branch of the Women’s Society for the Protection of Animals, Frances, with her sister Emma Clarke, founded Australia’s first Bands of Mercy. Membership of the Bands required pledging on entry:

I promise to protect all animals from ill-treatment with all my power. When I am compelled to take the life of any creature, I will spare all needless pain.

The Bands of Mercy were based on the Bands of Hope, formed in the United Kingdom to support the temperance movement and, like them, were formal voluntary organisations in communities. Founded in 1875, they helped young people learn about and model the humane treatment of animals, coming under the RSPCA from 1882, the same year they were introduced into the United States. It was Levvy who then introduced Bands of Mercy in Australia in the mid-1880s, growing the membership from 15 to over 20,000 people over her life.

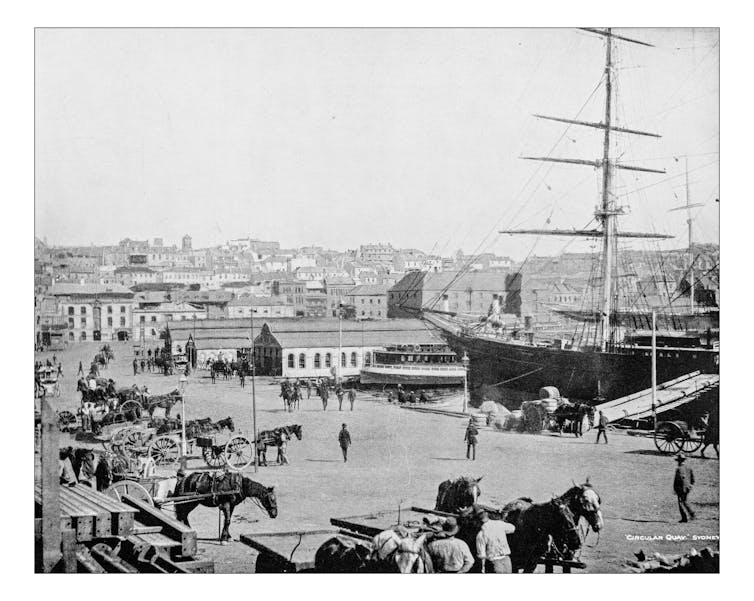

Circular Quay harbour, Sydney, Australia, undated.

Stock photo ID: 544124516, uploaded 4 July 2016

Circular Quay harbour, Sydney, Australia, undated.

Stock photo ID: 544124516, uploaded 4 July 2016

Born in Penrith, Frances was one of four children of Barnett and Sarah Levey, the former a watch-maker and theatre director, both from London. When Levey died in 1837, his widow converted from Judaism to Christianity, which appears to have shaped Frances’s moral and religious outlook. On their mother’s death Frances and her sister Emma adopted the surname Levvy. After moving to Newtown in Sydney in 1874 with her sister, Frances later went to Waverley where she lived - single and focused on her mission - until her death in 1924.

Clues to what motivated Levvy’s lifelong dedication to the humane movement are found in The Daily Telegraph of Tuesday 30 January 1906. There, the reporter describes Levvy in ways that map onto ideas emergent at the time that women’s apparently natural propensity to nurture in the private sphere could spill into the public arena and contribute to social progress.

Levvy is painted as having:

a gentle, persuasive manner … intensely in earnest in her whole-hearted and disinterested wish to save our dumb [sic] friends from ill-treatment … the right woman in the right place. It is so eminently a woman’s work which she has undertaken, to inculcate gentleness and kindness in the hearts of the children of our city …

When asked by the reporter if she thought animals have souls, Levvy replied:

It seems to me that it is not at all improbable. There is an evident wish to believe it.

‘Loving friend of dumb animals’

Over several decades, Levvy effectively harnessed the printed word’s power to influence how animals were treated. She developed and edited a monthly periodical, The Band of Mercy and Humane Journal (1887–1923), which inspired offshoots such as The Band of Mercy Advocate (1887–1891).

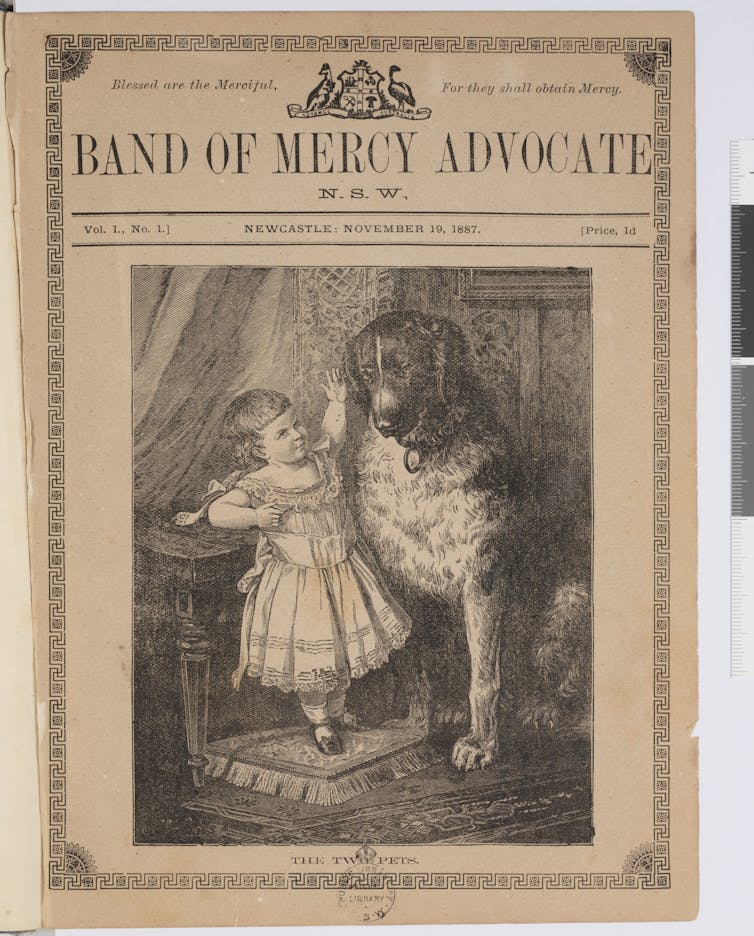

The first edition of the Band of Mercy Advocate.

to come

The first edition of the Band of Mercy Advocate.

to come

Levvy was equally adept at building community networks, and coalitions and defying moral strictures regarding the public conduct expected of “ladies”. As one report on her work (replete with deeply gendered and class-based assumptions) noted:

The draymen and vanmen at the wharves and the drivers at the cab stands are regularly visited by this loving friend of dumb animals, from whom they receive copies of the Band of Mercy journal. This paves the way for a little general conversation on the subject of kindness to animals, and then some particular instance is … [introduced]; a horse has gone lame or has a sore shoulder, which should be dressed with a decoction of tannin — or the flies are stinging and worrying, and it is suggested that … pennyroyal added to a pint of olive oil should be passed lightly over the horses to secure their immunity from this pest.

A horse carriage with rider, Sydney, Australia, 1924.

Stock photo ID: 1065147264, uploaded 8 November 2018

A horse carriage with rider, Sydney, Australia, 1924.

Stock photo ID: 1065147264, uploaded 8 November 2018

It has been suggested that Levvy’s “greatest capacity was for writing” and my own research shows that an astute use of the periodical press ensured her work was known and supported. The editors of Boston’s The Woman’s Journal, wrote glowingly of her work in 1888, noting her journal provided “a place of record for the good deeds done”. In 1906, it described the journal as having “the distinction of being the first newspaper of the kind in Australia”.

The power of the press is worth stressing here, because it underpinned growing freedoms of speech and capacities to challenge the status quo that Levvy tapped into. Debates in the press around animal protection touched on fashion (and its relationship to prescriptive forms of femininity and consumerism) and sport (with its association with betting).

S.T. Gill, Kangaroo Hunting, The Death, from his Australian Sketchbook (1865).

National Library of Australia

S.T. Gill, Kangaroo Hunting, The Death, from his Australian Sketchbook (1865).

National Library of Australia

Seeing young people as agents of change

In her writing and activism, Levvy often turned to children and, through them, to women — whose power she thought should extend from private to public spheres.

The 1906 report in The Daily Telegraph also describes how she gave lessons on animal protection at schools. She educated boys about the most humane method of transit of stock by rail, or training a colt to harness and saddle. And she set the following essay topics for mixed sex, upper level classes:

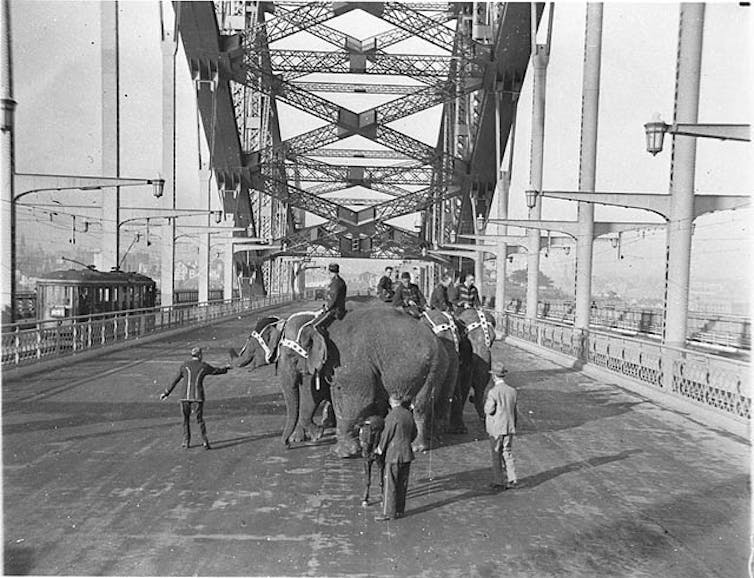

Does civilisation in any way depend on possession of animals? Give reasons, state requirements, and value of poultry-keeping, incubator, food, incidental diseases. Is it suitable work for women and girls? Bee-keeping: Requirements and value. Hives, honey-producing flowers, food in winter, etc. Is it suitable work for women and girls? Is the exhibition of wild animals in travelling menageries consistent with humanity? Give your reasons.

Six Wirths’ Circus elephants with their attendants and a Shetland pony cross the Sydney Harbour Bridge as part of a publicity stunt in 1932.

Wikimedia Commons

Six Wirths’ Circus elephants with their attendants and a Shetland pony cross the Sydney Harbour Bridge as part of a publicity stunt in 1932.

Wikimedia Commons

Levvy, herself, reflected in 1906 (in relation to her work on equine welfare):

The difference between now and twenty years ago … is most marked. It is hardly ever now that one sees a sore-backed, lame, miserable-looking horse in the streets. Look at the cab horses and cart horses, what fine, well-kept animals they are.

After Levvy’s death on 24 November 1924, the former NSW Minister for Education, Joseph Carruthers, paid tribute to her and announced a school essay competition in her name. Internationally, the Bands of Mercy began to lose momentum between the world wars, and languished after 1945. Although Peter Chen has provided a detailed time-line of developments in animal welfare in Australia, he does not record a date for when they ceased here.

Levvy was of her time. She was, for example, deeply immersed in the progressive, democratising, and evangelical impulses that marked the 19th century.

But she was, I think, also ahead of her time, being among those women who understood and used the power of the press for socially transformative ends, and who recognised that young people are not citizens in waiting but active and influential agents for change.

At a time when the treatment of both animals and children was often questionable, and often based on narrow ideas of them as property, her actions and ideas were quietly radical and highly effective.

Authors: Elaine Stratford, Professor, University of Tasmania