Cyclones, screens, lost souls: how the ghosts we believe in reflect our changing fears

- Written by Geir Henning Presterudstuen, Senior Lecturer in Anthropology, Western Sydney University

The ghosts of Halloween decorations provide light entertainment, but our enduring fascination for and fear of them is far from child’s play.

Polls indicate 35% of Australians believe in the existence of ghosts, figures echoed in the US and the UK. Indeed, belief in ghosts is so common across the world they are considered a cultural universal.

Tracing them through time and space – from dusty spirits to ghosts in machines – reveals ghosts have a particular knack for reflecting the specific anxieties of their historical moment. Paying attention to what makes them scary, can teach us about ourselves.

Small spooky girl ghosts are popular with modern storytellers.

The Ring, IMDB

Small spooky girl ghosts are popular with modern storytellers.

The Ring, IMDB

Spiritual limbo

Stuck in a space between life and death, ghosts are ambiguous and unsettled. Wherever they emerge they seem intent on bringing the past into the present.

The European Middle Ages abounded with sightings of ghosts – returned from their graves to frighten the living. These were thought to be the returning spirits, or revenants, of individuals who had suffered “bad deaths”: having been murdered, leading sinful lives, or being denied a proper burial.

Read more: 5 things to know about the traditional Christian doctrine of hell

Historian William of Newburgh chronicled one famous story of a Berwick man who died after falling from bedroom rafters while spying on his unfaithful wife. Despite a Christian burial, he returned with a pack of wild dogs to haunt men.

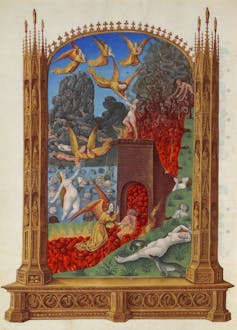

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Folio 113v - Purgatory.

Wikiart

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Folio 113v - Purgatory.

Wikiart

Postmortem revival was seen as a sign of moral and spiritual failings and was dealt with accordingly: bodies were exhumed and stakes driven through hearts. The Berwick ghost was eventually laid to rest after the husband’s corpse was dug up, dismembered and burnt.

With the concept of purgatory established in most Christian teachings by the 1400s, the understandings of revenants changed. No longer seen as unequivocally evil characters whose souls were forever lost, revenants came to reflect a state of spiritual limbo.

This moral ambiguity mirrored spiritual traditions elsewhere, such as East Asia where ghosts feature in ritual performances in both good and evil guises.

Harbingers of danger

In Fiji, where I have conducted ethnographic fieldwork for more than a decade, ghosts emerge in a number of shapes and forms. Once seen as protectors of the land and guardians of custom, increasingly they are taken as portents for new threats.

Villagers in Fiji reported ghostly visits from lost neighbours following Cyclone Winston.

Joseph Hing/AAP

Villagers in Fiji reported ghostly visits from lost neighbours following Cyclone Winston.

Joseph Hing/AAP

In 2016, members of a village reported being haunted by the ghost of a friend several weeks after he had drowned during Cyclone Winston.

Night after night the ghost was seen and heard searching for his bed and asking for food near the ruins of his old house. For villagers still recovering from the most violent cyclone in memory, this ghostly presence reflected and fuelled growing concerns about climate change and the sustainability of village life.

The ghost was read as a harbinger of danger, and the message it brought was scarier than the creature itself.

Old ghosts, new fears

Over time, ghosts have reflected geographically specific histories and concerns.

Native American spirits have moved from traditional ghostly pasts into the contemporary politics of heritage, land ownership and recognition. They also reportedly drive cars and intervene in construction work.

Indigenous Australian traditions feature a vast array of spiritual beings. Warwick Thornton’s 2013 docudrama The Darkside, developed from a national callout for Indigenous ghost stories, reimagined 13 tales and showed how the haunting presence of the past can be a defining part of life for many contemporary Australians.

Old haunts come to life in The Darkside, a film developed after a national call out for Indigenous ghost stories.Anthropologist Mahnaz Alimardanian documented the ghostly figure of the Burnt Woman who reportedly haunts a mission in Northern NSW. With a face disfigured by fire, Burnt Woman is recognisable as a local Indigenous woman who was killed in the early days of colonial settlement, serving both as a reminder of the violence of past encounters and reflecting the damage of ongoing social injustices.

Her appearance to believers as a seductress of men adds a layer of social commentary in a community where gender violence is a significant problem.

What scares us now?

Ghosts in contemporary popular culture similarly reflect people’s current fears. The 2002 film The Ring - a remake of a cult Japanese film - drew on human anxieties about how technology might take hold of our lives, a fear that seems justified when a vengeful ghost crawls out of a TV screen.

In the TV series Black Mirror, a widow uses technology to revive her husband’s spirit.

IMDB

In the TV series Black Mirror, a widow uses technology to revive her husband’s spirit.

IMDB

These fears have also been canvassed in an episode of the Netflix series Black Mirror called Be Right Back in which a grieving young widow uses artificial intelligence to interact with her late husband.

In other modern ghost stories, spectres are depicted as grappling with the same existential issues haunting many modern humans. David Lowery’s A Ghost Story (2017) centres on a ghost’s difficulties in dealing with its own death and letting go of its past, issues a contemporary audience might feel familiar with in a time of rapid social change.

Where is a Ghostbuster when you need one? A Ghost Story (2017) deals with loss in a changing world.This quality – ghosts’ ability to bring out our innermost subconscious fears – is what makes them such compelling and universally meaningful beings.

Authors: Geir Henning Presterudstuen, Senior Lecturer in Anthropology, Western Sydney University