Curious Kids: how does an optical illusion work?

- Written by Cedric van den Berg, PhD student, The University of Queensland

How does an optical illusion work? – Scarlett, age 8, Shellharbour, NSW.

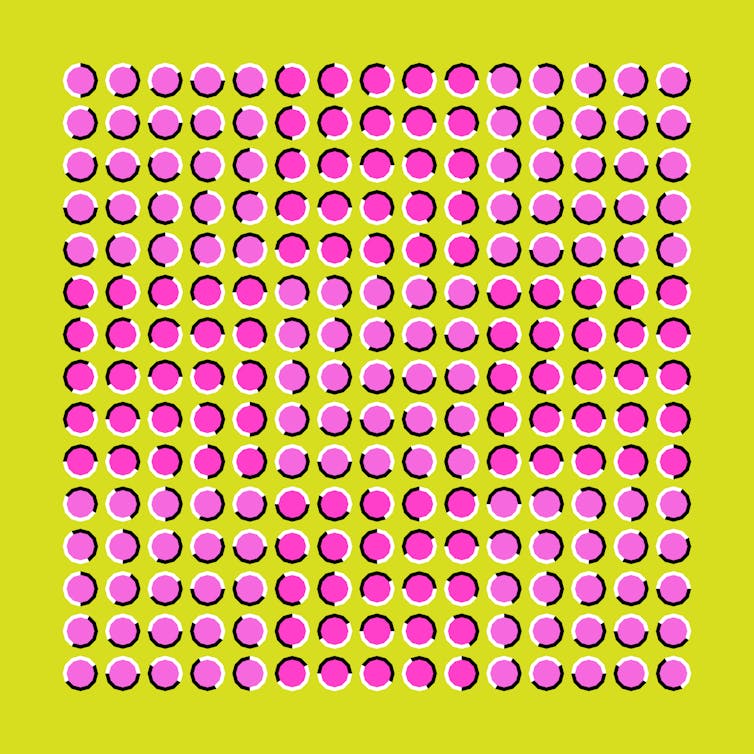

Take a look at this image and move your eyes across the pattern:

Your eyes tell the brain what it sees and the brain fills in the missing information.

Shutterstock

Your eyes tell the brain what it sees and the brain fills in the missing information.

Shutterstock

Do you see something moving? Well, it’s not really moving. It’s just your brain being confused by what your eyes tell it.

The confused brain

Our brain is like a blind supercomputer; it’s very smart, but it can’t see. It’s just a really smart blob.

To figure out what it needs, our eyes tell our brain what the things around us look like. The problem is our eyes only know a handful of words to describe what they see.

Sometimes, our brain gets confused by what the eyes are trying to tell it.

This can mean the brain thinks things are moving when actually they’re still. Or you might “see” shapes, shades or colours that aren’t really there.

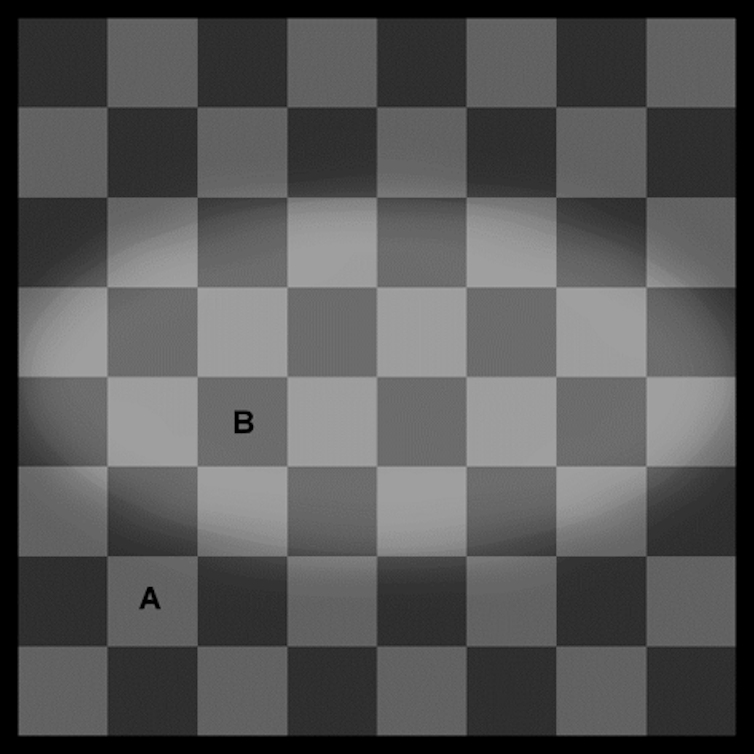

For example, look at Square A and Square B in this picture:

Do Square A and Square B look different?

Queensland Brain Institute, Author provided

Do Square A and Square B look different?

Queensland Brain Institute, Author provided

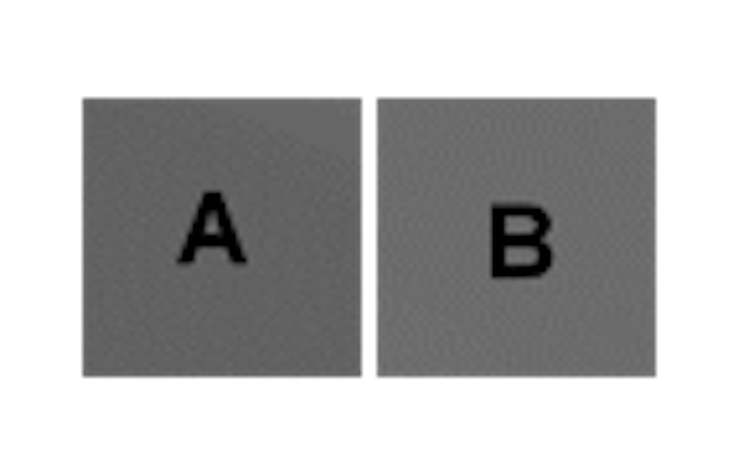

Square A looks lighter, but is actually darker than Square B. In fact, here’s what both squares look like side by side:

Queensland Brain Institute, Author provided (No reuse)

Read more:

Curious Kids: What was the first computer?

A simple language

Our eyes and brain speak to each other in a very simple language, like a child who doesn’t know many words. Most of the time that’s not a problem and our brain is able to understand what the eyes tell it.

The colour of an orange, the size of a chair, how far away the door is – your brain knows all these things because the eyes told it so in simple language.

But your brain also has to “fill in the blanks” meaning it has to make some guesses based on the simple clues from the eyes. Mostly those guesses are right (for example, I can see the door looks about this big and the light falls on it that way, so my brain is taking these simple clues and guessing the door is about one metre away).

A wrong guess

Sometimes, however, the brain guesses wrong.

Queensland Brain Institute, Author provided (No reuse)

Read more:

Curious Kids: What was the first computer?

A simple language

Our eyes and brain speak to each other in a very simple language, like a child who doesn’t know many words. Most of the time that’s not a problem and our brain is able to understand what the eyes tell it.

The colour of an orange, the size of a chair, how far away the door is – your brain knows all these things because the eyes told it so in simple language.

But your brain also has to “fill in the blanks” meaning it has to make some guesses based on the simple clues from the eyes. Mostly those guesses are right (for example, I can see the door looks about this big and the light falls on it that way, so my brain is taking these simple clues and guessing the door is about one metre away).

A wrong guess

Sometimes, however, the brain guesses wrong.

Our eyes and brains evolved to be quite sensitive to movement, even when it is not really there.

Shutterstock

For example, it thinks our eyes told it something is moving but that’s not what the eyes meant to say to the brain. (Our brains and eyes evolved to be quite sensitive about movement because in pre-historic times it was a big help if you could spot movement early and often. A slight rustle in the bushes could mean a predator was nearby and it was time to run away. Spotting movement early could save your life!)

Optical illusions happen when our brain and eyes try to speak to each other in simple language but the interpretation gets a bit mixed-up.

But how and why?

A lot of scientists have worked very hard for many years trying to understand how optical illusions work. But the truth is, in many cases, we still don’t know for sure exactly how our brain and eyes work together to create these illusions.

We know that information that our eyes gather goes on a long, complicated journey as it travels to the brain. Some of the confusion happens early in that journey. Other optical illusions can only be explained by really complicated processes way down the line in that journey.

In general, the further down the line these “confusions” occur, the less scientists tend to know about exactly how they happen.

But who knows? Maybe you will grow up to be part of the research team that cracks the code.

Read more:

Curious Kids: do different people see the same colours?

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

Our eyes and brains evolved to be quite sensitive to movement, even when it is not really there.

Shutterstock

For example, it thinks our eyes told it something is moving but that’s not what the eyes meant to say to the brain. (Our brains and eyes evolved to be quite sensitive about movement because in pre-historic times it was a big help if you could spot movement early and often. A slight rustle in the bushes could mean a predator was nearby and it was time to run away. Spotting movement early could save your life!)

Optical illusions happen when our brain and eyes try to speak to each other in simple language but the interpretation gets a bit mixed-up.

But how and why?

A lot of scientists have worked very hard for many years trying to understand how optical illusions work. But the truth is, in many cases, we still don’t know for sure exactly how our brain and eyes work together to create these illusions.

We know that information that our eyes gather goes on a long, complicated journey as it travels to the brain. Some of the confusion happens early in that journey. Other optical illusions can only be explained by really complicated processes way down the line in that journey.

In general, the further down the line these “confusions” occur, the less scientists tend to know about exactly how they happen.

But who knows? Maybe you will grow up to be part of the research team that cracks the code.

Read more:

Curious Kids: do different people see the same colours?

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

Authors: Cedric van den Berg, PhD student, The University of Queensland

Read more http://theconversation.com/curious-kids-how-does-an-optical-illusion-work-123008