Science prizes are still a boys' club. Here's how we can change that

- Written by Justine Shaw, Conservation Biologist, The University of Queensland

This year, five of the seven Prime Minister’s Prizes for Science were awarded to women. While this is a welcome development, the great majority of awards and prizes for science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) in Australia still go to men.

Our research has identified some of the key barriers to greater diversity among prize recipients and found ways those barriers can be removed.

Why awards aren’t just awards

In STEM, prizes and awards can make careers. They inform recruitment, probation reviews, promotions and grant success.

Yet STEM award recipients in Australia generally do not represent the diversity of the broader Australian STEM population. This contributes to slower career progression of people from under-represented groups, and means less diverse visible role models for future generations of STEM professionals.

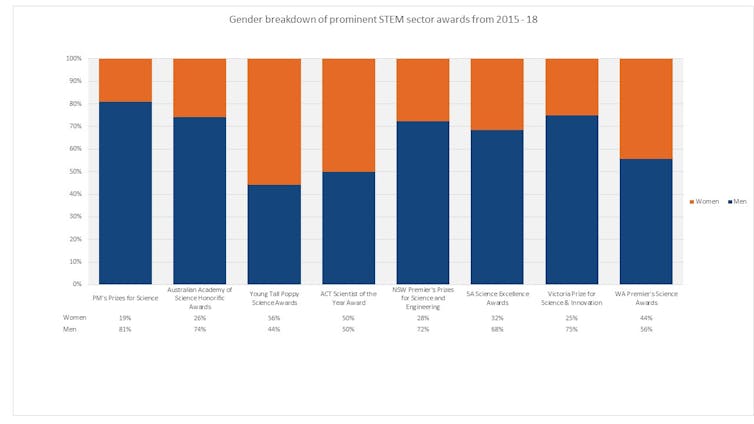

Across current prominent award and prize schemes in Australian STEM, men dominate, even in recent years.

Gender breakdown of award recipients in a selection of prominent STEM sector prizes and awards.

Numbers indicate the number of awards conferred in each scheme in 2015–2018.

Gender breakdown of award recipients in a selection of prominent STEM sector prizes and awards.

Numbers indicate the number of awards conferred in each scheme in 2015–2018.

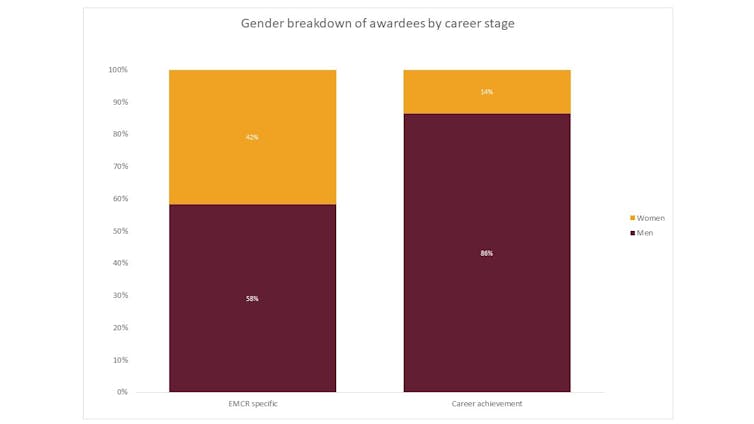

This imbalance is less pronounced among early career prizes, but grows over time.

Percentage of recipients who are men and women for 7 high-profile Australian awards for early and mid career researchers (ECMRs) and full careers. (PM’s Prizes for Science and Australia Prize, 1990–2018; AAS Honorific Awards, 1957–2019; Young Tall Poppy Science Awards, 1999–2018; ACT Scientist of the Year, 2015–2018; NSW Premier’s Prizes for Science and Engineering, 2008–2018; SA Science Excellence Awards, 2014–2018; Victoria Prize for Science and Engineering, 1998–2018; WA Scientist/Early-Career Researcher of the Year, 2002–2018)

Percentage of recipients who are men and women for 7 high-profile Australian awards for early and mid career researchers (ECMRs) and full careers. (PM’s Prizes for Science and Australia Prize, 1990–2018; AAS Honorific Awards, 1957–2019; Young Tall Poppy Science Awards, 1999–2018; ACT Scientist of the Year, 2015–2018; NSW Premier’s Prizes for Science and Engineering, 2008–2018; SA Science Excellence Awards, 2014–2018; Victoria Prize for Science and Engineering, 1998–2018; WA Scientist/Early-Career Researcher of the Year, 2002–2018)

To better understand the causes of this lack of diversity, we ran a series of facilitated workshops with early and mid-career researchers (EMCRs) working in STEM in Australia to investigate their attitudes to awards and prize schemes. We identified a number of barriers and discussed how they might be overcome.

Improving diversity

The first step is to identify where diversity is restricted.

A lack of diversity in award recipients may reflect the pool of applicants, which could be due to a lack of diversity within the discipline itself and/or a failure to reach all eligible people when promoting the award.

Read more: Take it from us: here's what we need in an ambassador for women in science

Applications should at least reflect the proportion of women and minority groups within the eligible cohort. As a starting point, it has been proposed that awards should aim for at least 30% of applicants to consist of women and members of minority groups.

Alternatively, if applicants are diverse but recipients are not, it suggests a failing in how winners are chosen (such as the selection criteria, how success is measured, or how decisions are reviewed).

Identifying the barriers

Reach

People who don’t know about an award can’t apply for it, so reaching the whole target audience is vital. Prizes and awards – like other key elements in career progression such as job openings, funding schemes and opportunities for collaboration or promotion – are often discussed via informal networks. But these networks themselves often have limited diversity.

Time

Applications can be time-consuming, and women in STEM often have additional time pressures and responsibilities. What’s more, women are more likely to work part-time, which means they have less time to devote to seemingly less essential tasks like award applications. Women in STEM are also more likely to be expected to act as role models and mentors and participate in committees and outreach activities.

Streamlined application forms can cut the time involved. Current automated methods of collecting information (such as Expert Connect) could be utilised more efficiently. Submission dates for award applications should not coincide with dates for major grant or funding applications. In Australia, major grant rounds usually fall in the period of December to March.

Advertising

Many awards and prizes are named after pioneers within the discipline – often older white men – and their names and images are used in advertising. This can discourage applicants who may feel they don’t “fit” with the scheme.

One way to address this is to showcase mentors and champions in the advertising campaign to demystify the application process, particularly if past winners are diverse. Organisations should encourage senior scientists and past award recipients to act as mentors and actively seek out junior scientists to apply.

Application process

The common requirement for third-party nominations, rather than self-applications, and referees’ letters, can also be significant barriers. Another is the way age and career interruptions are treated.

To address these barriers, awards can take simple steps like only asking for referees’ reports from short-listed applicants and including a standard field for career interruptions that all applicants need to fill in.

Selection process

Traditional metrics such as numbers of publications, citations and citation indices can be rigid and exclude scientists with diverse career paths, and also disadvantage interdisciplinary researchers and those with career interruptions.

There are a number of ways to remove to this barrier.

Read more: Women still find it tough to reach the top in science

Diverse selection panels can limit bias and unconscious bias. Organisations should be transparent, disclosing the selection criteria and the identities of panel members. Criteria should include non-traditional metrics including research impact, outreach activities, industry engagement, patents, policy, software, mentorship, supervision, teaching, advocacy and committee service.

It’s clear a scientist’s success contributes to further success. Awards lead to more awards.

Too often, an institution will choose a single woman to promote for awards and honours and feel they’ve done their bit for diversity. Instead, institutions should look more broadly at their pool of potential applicants.

Sector-wide change is required to increase diversity among award and prize recipients. Lack of diversity even in smaller prizes can impact other levels, which then perpetuates the lack of diversity across the STEM sector.

Authors: Justine Shaw, Conservation Biologist, The University of Queensland

Read more http://theconversation.com/science-prizes-are-still-a-boys-club-heres-how-we-can-change-that-124995